Record Data

Source citation

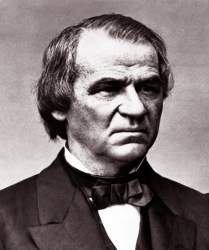

Reprinted in John Savage, The Life and Public Services of Andrew Johnson, Seventeenth President of the United States... (New York: Derby and Miller Publishers, 1866), 347-349.

Recipient (to)

Delegation of Southern Refugees

Type

Speech

Date Certainty

Exact

Transcription

The following text is presented here in complete form, as it originally appeared in print. Spelling and typographical errors have been preserved as in the original.

It is hardly necessary for me on this occasion to say that my sympathies and impulses in connection with this nefarious rebellion beat in unison with yours. Those who have passed through this bitter ordeal, and who participated in it to a great extent, are more competent, as I think, to judge and determine the true policy which should be pursued. I have but little to say on this question in response to what has been said. It enunciath and expresses my own feelings to the fullest extent; and in much better language than I can at the present moment summon to my aid. The most I can say is that, entering upon the duties that have devolved upon me under circumstances that are perilous and responsible, and being thrown into the position I now occupy unexpectedly, in consequence of the sad event, the heinous assassination which has taken place—in view of all that is before me and the circumstances that surround me—I cannot but feel that your encouragement and kindness are peculiarly acceptable and appropriate. I do not think that you, who have been familiar with my course—you who are from the South—deem it necessary for me to make any professions as to the future on this occasion, nor to express what my course will be upon questions that may arise. If my past life is no indication of what my future will be, my professions were both worthless and empty; and in returning you my sincere thanks for this encouragement and sympathy, I can only reiterate what I have said before, and, in part, what has just been read. As far as clemency and mercy are concerned, and the proper exercise of the pardoning power, I think I understand the nature and character of the latter. In the exercise of clemency and mercy that pardoning power should be exercised with caution. I do not give utterance to my opinions on this point in any spirit of revenge or unkind feelings. Mercy and clemency have been pretty large ingredients in my compound, having been the Executive of a State, and thereby placed in a position in which it was necessary to exercise clemency and mercy. I have been charged with going too far, being too lenient, and have become satisfied that mercy without justice is a crime, and that when mercy and clemency are exercised by the Executive it should always be done in view of justice, and in that manner alone is properly exercised that great prerogative. The time has come, as you who have had to drink this bitter cup are fully aware, when the American 'people should be made to understand the true nature of crime. Of crime generally, our people have a high understanding, as well as of the necessity for its punishment; but in the catalogue of crimes there is one, and that the highest known to the law and the Constitution, of which, since the days of Jefferson and Aaron Burr, they have become oblivious. That is—treason. Indeed, one who has become distinguished in treason, and in this rebellion, said that "when traitors become numerous enough treason becomes respectable, and to become a traitor was to constitute a portion of the aristocracy of the country." God protect the people against such an aristocracy. Yes, the time has come when the people should be taught to understand the length and breadth, the depth and height, of treason. An individual occupying the highest position among us was lifted to that position by the free offering of the American people—the highest position on the habitable globe. This man we have seen, revered and loved—one who, if he erred at all, erred ever on the side of clemency and mercy ~that man we have seen treason strike, through a fitting instrument, and we have beheld him fall like a bright star from its sphere. Now, there is none but would say, if the question came up, what should be done with the individual who assassinated the Chief Magistrate of the nation l—he is but a man— one man, after all; but if asked what should be done with the assassin, what should be the penalty, the forfeit exacted? I know what response dwells in every bosom. It is, that he should pay the forfeit with his life. And hence we see there are times when mercy and clemency, without justice, become a crime. The one should temper the other, and bring about that proper mean. And if we would say this when the case was the simple murder of one man by his fellow man, what should we say when asked what shall be done with him or them or those who have raised impious hands to take away the life of a nation composed of thirty millions of people? What would be the reply to that question? But while in mercy we remember justice, in the language that has been uttered, I say, justice towards the leaders, the conscious leaders; but I also say amnesty, conciliation, clemency and mercy to the thousands of our countrymen whom you and I know have been deceived or driven into this infernal rebellion. And so I return to where I started from, and again repeat, that it is time our people were taught to know that treason is a crime, not a more political difference, not a mere contest between two parties, in which one succeeded and the other has simply failed. They must know it is treason; for if they had succeeded the life of the nation would have been rent from it—the Union would have been destroyed. Surely the Constitution sufficiently defines treason. It consists in levying war against the United States, and in giving their enemies aid and comfort. With this definition it requires the exercise of no great acumen to ascertain who are traitors. It requires no great perception to tell us who have levied war against the United States; nor does it require any great stretch of reasoning to ascertain who has given aid to the enemies of the United States; and when the Government of the United States does ascertain who are the conscious and intelligent traitors, the penalty and the forfeit should be paid. I know how to appreciate the condition of being driven from one’s home. I can sympathize with him whose all has been taken from him—with him who has been denied the place that gave his children birth. But let us, withal, in the restoration of true government, proceed temperately and dispassionately, and hope and pray that the time will come, as I believe, when all can return and remain at our homes, and treason and traitors be driven from our land; when again law and order shall reign, and the banner of our country be unfurled over every inch of territory within the area of the United States. In conclusion, let me thank you most profoundly for this encouragement and manifestation of your regard and respect, and assure you that I can give no greater assurance regarding the settlement of this question than that I intend to discharge my duty, and in that way which shall, in the earliest possible hour, bring back peace to our distracted country. And I hope the time is not far distant when our people can all return to their homes and firesides, and resume their various avocations.