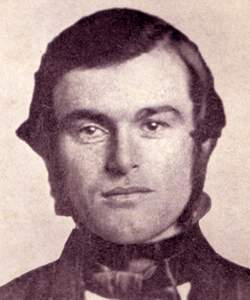

Dickinson Gorsuch (Smedley, 1883)

Scholarship

Dickerson [Dickinson] fell wounded. He arose and was shot again. The old man, after fighting valiantly, was killed. The others of the slaveholders with the United States Marshal and his aids fled, pursued by the negroes. While Dickerson [Dickinson] lay bleeding in the edge of the woods, Joseph P. Scarlett, a Quaker, came up and protected him from the infuriated negroes, who pressed forward to take his life. One was in the act of shooting, when Joseph pushed him aside, saying: "Don't kill him."…

When the fight had ended [William] Parker returned to his house. There lay Edward Gorsuch near by dead. Dickerson, he heard, was dying, and others were wounded. The victor viewed the field of his contest, but he possessed too much of the noble spirit of manhood to feel a pride in the death of his adversary. He offered the use of anything in his house that might be needed for the comfort of the wounded.

He then went to Levi Pownall's and asked if Dickerson [Dickinson] could not be brought there and cared for, remarking that one death was enough. He regretted the killing, and said it was not he who had done it…Dr. A. P. Patterson was sent for and examined Dickerson's [Dickinson] wounds. He pronounced them serious, but not fatal. Levi Pownall put a soft bed in a wagon and had Dickerson [Dickinson] conveyed upon it to his house, where for three weeks he received as assiduous care and attention as though he had been one of their own household. He did not expect this from Quakers, whom he had learned to despise as abolitionists. As each became acquainted with the other during his stay, they grew to esteem him for the noble characteristics which he possessed, and he manifested gratitude for the kind and home-like nursing he received at their hands. They told him they had no sympathy with the institution of slavery, but that should not deter them from giving him the kind care and sympathy due from man to man.

When the fight had ended [William] Parker returned to his house. There lay Edward Gorsuch near by dead. Dickerson, he heard, was dying, and others were wounded. The victor viewed the field of his contest, but he possessed too much of the noble spirit of manhood to feel a pride in the death of his adversary. He offered the use of anything in his house that might be needed for the comfort of the wounded.

He then went to Levi Pownall's and asked if Dickerson [Dickinson] could not be brought there and cared for, remarking that one death was enough. He regretted the killing, and said it was not he who had done it…Dr. A. P. Patterson was sent for and examined Dickerson's [Dickinson] wounds. He pronounced them serious, but not fatal. Levi Pownall put a soft bed in a wagon and had Dickerson [Dickinson] conveyed upon it to his house, where for three weeks he received as assiduous care and attention as though he had been one of their own household. He did not expect this from Quakers, whom he had learned to despise as abolitionists. As each became acquainted with the other during his stay, they grew to esteem him for the noble characteristics which he possessed, and he manifested gratitude for the kind and home-like nursing he received at their hands. They told him they had no sympathy with the institution of slavery, but that should not deter them from giving him the kind care and sympathy due from man to man.

R.C. Smedley, History of the Underground Railroad in Chester and the Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania (Lancaster, PA: John A Hiestand, 1883), 119-120.