Record Data

Source citation

"United States," The American Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year 1865 ... (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1869), 809-810.

Type

Letter

Date Certainty

Exact

Transcriber

John Osborne, Dickinson College

Transcription date

Transcription

The following text is presented here in complete form, as it originally appeared in print. Spelling and typographical errors have been preserved as in the original.

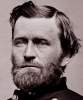

Headquarters Army of the United States, December 18, 1865.

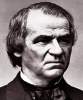

To His Excellency A. Johnson, President of the United States.

Sir: In reply to your note of the 16th instant, requesting a report from me giving such information as maybe in possession of, coming within the scope of inquiries made by the Senate of the United States in their resolution of the 12th instant, I have the honor to submit the following with your approval, and also that of the Honorable Secretary of War.

I left Washington on the 27th of last month for the purpose of making a tour of inspection throughout some of the Southern States lately in rebellion, and to see what changes were necessary in the disposition of the military forces of the country, and how these forces could be reduced and expenses curtailed, etc., and to learn, as far as possible, the feelings and intentions of the citizens of the States toward the General Government. The State of Virginia being so accessible to Washington City, and information from this quarter, therefore, being readily obtained, I hastened through the State without conversing or meeting with any of the citizens. In Raleigh, N. C, I spent one day; in Charleston, S. C, two; and in Savannah and Augusta, Ga., each one day. Both in travelling and while stopping I saw much and conversed freely with citizens of those States, as well as with officers of the army who have been stationed among them. The following are the conclusions come to by me:

I am satisfied the mass of thinking men of the South accept the present situation of affairs in good faith. The questions which have hitherto divided the sentiments of the people of the two sections— slavery and State rights, or the right of a State to secede from the Union—they regard as having been settled forever by the highest tribunal of arms that man can resort to. I was pleased to learn from the leading men whom I met that they not only accepted the decision arrived at as final, but now that the smoke of battle has cleared away, and time has been given for reflection, that this decision has been a fortunate one for the whole country, they receiving the like benefits from it with those who opposed them in the field and in the council. Four years of war, during which the law was executed only at the point of the bayonet throughout the States in rebellion, have left the people, possibly, in that condition not to yield that ready obedience to civil authority the American people have generally been in the habit of yielding. This would render the presence of small garrisons throughout those States necessary until such time as labor returns to its proper channel, and civil authority is fully established. I did not meet any one, either those holding places under the Government or citizens of Southern States, who thought it practicable to withdraw the military from the South at present. The white and black mutually require the protection of the General Government, here is such universal acquiescence in the authority of the General Government throughout the portions of the country visited by me, that the mere presence of a military force, without regard to numbers, is sufficient to maintain order.

The good of the country requires that a force be kept in the interior where there are many freedmen. Elsewhere in the Southern States than at forts on the sea-coast no force is necessary. The soldiers should all be white troops. The reasons for this are obvious. Without mentioning many of them, the presence of black troops, lately slaves, demoralizes labor both by their advice and furnishing in their camps a resort for the freedmen for long distances around. White troops generally excite no opposition, and therefore a smaller number of them can maintain order in a given district. Colored troops must be kept in bodies sufficient to defend themselves. It is not the thinking man who would do violence toward any class of troops sent among them by the General Government, but the ignorant in some places might; and the late slave, too, who might be imbued with the idea that the property of his late master should by right belong to him, at least should have no protection from the colored soldier. There is no danger of a collision being brought on by such causes.

My observations lead me to the conclusion that the citizens of the Southern States are anxious to return to self-government within the Union as soon as possible; that whilst reconstructing they want and require protection from the Government that they think is required of the Government, and is not unmilitary to them as citizens, and if such a course was pointed out they would pursue it in good faith. It is to be regretted there cannot be a greater commingling at this time between the citizens of the two sections, and particularly of those intrusted with the lawmaking power.

I did not give the operations of the Freedmen's Bureau that attention I would have done if more time had been at my disposal. Conversation, however, on the subject with officers connected with the Bureau, lead me to think that in some of the States its affairs have not been conducted with good judgment or economy, and that the belief widely spread among the freedmen of the Southern States that the lands of their former owners will, at least in part, be divided among them, has come from agents of the Bureau. This belief is seriously interfering with the willingness of the freedmen to make contracts for the coming year. In some form the Freedmen's Bureau is an absolute necessity until the civil law is established and enforced, securing to freedmen their rights and full protection. At present, however, it is independent of the military establishment of the country, and seems to be operated by the different agents of the Bureau, according to their individual notions. Everywhere, General Howard, the able head of the Bureau, has made friends by the just and fair instructions and advice he gave, but the complaint in South Carolina was that when he left, things went on as before. Many, perhaps a majority of the agents of the Freedmen's Bureau, advised the freedmen that by their own industry they must expect to live. To this end they endeavored to secure employment for them, and to see that both of the contracting parties complied with their engagements. In some cases, I am sorry to say, the freedman's mind does not seem to be disabused of the idea that the freedman has a right to live without care or provision for the future. The effect of this belief in the distribution of the lands is idleness, and accumulation in camps, towns, and cities.

In such cases, I think it will be found, that vice and disease will tend to the extermination or great destruction of the colored race. It cannot be expected that the opinions held by men at the South for years can be changed in a day, and therefore the freedrmen require for a few years not only laws to protect them, but the fostering care of those who will give them good counsel and on whom they can rely.

The Freedmen'a Bureau being separated from the military establishment of the country, requires all the expense of a separate organization. One does not necessarily know what the other is doing, or what orders they are acting under. It seems to me this could be corrected by regarding every officer on duty with the troops in the Southern States as agents of the Freedmen's Bureau, and then have all orders from the head of the bureau sent through the department commanders. This would create a responsibility that would beget uniformity of action throughout the South, and would insure the orders and instructions from the head of the Bureau being carried out, and would relieve from duty and pay a large number of the employes of the Government.

I have the honor to he, very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

U. S. GRANT, Lieut.-General."