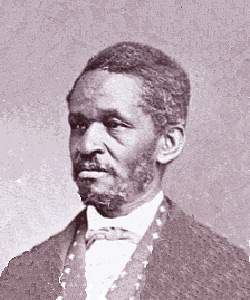

Lewis Hayden (American National Biography)

Scholarship

Separated from his family by the slave trade at age ten, he was eventually owned by five different masters. The first, a Presbyterian clergyman, traded him for a pair of horses. The second, a clock peddler, took Hayden along on his travels throughout the state, exposing him to the variety of forms that the "peculiar institution" could take. About 1830 he married Harriet Bell, also a slave. They had three children; one died in infancy, another was sold away, and a third remained with the couple. Hayden's third owner, in the early 1840s, whipped him often. These experiences stirred his passionate personal hatred for bondage. Hayden secretly learned to read and write, using the Bible and old newspapers as study materials. By 1842, when he belonged to Thomas Grant and Lewis Baxter of Lexington, he began to contemplate an escape. Because his last owners hired him out to work in a local hotel, he had greater freedom than most slaves, which made it easier to flee. In September 1844 Lewis, Harriet, and their remaining son were spirited away to Ohio and then on to Canada West (now Ontario), by local teachers and Underground Railroad agents Calvin Fairbanks and Delia Webster.

Roy E. Finkenbine, "Hayden, Lewis," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00315.html.

Lewis Hayden (Blockson, 1994)

Reference

Hayden was himself a slave who had escaped from Kentucky in 1816 and settled in Boston. He made his large, four-story home on Beacon Hill a station stop. When William and Ellen Craft made their daring escape in 1848 from Macon, Georgia, they were forwarded to Hayden’s home. Upon recovering the Crafts, Hayden placed himself by two kegs of gunpowder and stood with a candle, grimly determined to blow up his home, the Crafts and himself, rather than surrender his guests if slave hunters came to his door.

In 1851, Hayden led by a group of Boston African-Americans in liberating, by force, a fugitive slave named Frrederick Jenkins (known also as Shadrach) from federal officers. Hayden operated his station with his wife Harriet, and assisted his friend Harriet Tubman when she passed through Boston. He was elected to serve in the Massachusetts Legislature in 1873. After his death in 1889, a scholarship fund at Harvard University was established by his widow.

In 1851, Hayden led by a group of Boston African-Americans in liberating, by force, a fugitive slave named Frrederick Jenkins (known also as Shadrach) from federal officers. Hayden operated his station with his wife Harriet, and assisted his friend Harriet Tubman when she passed through Boston. He was elected to serve in the Massachusetts Legislature in 1873. After his death in 1889, a scholarship fund at Harvard University was established by his widow.

Charles L. Blockson, Hippocrene Guide to The Underground Railroad (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1994), 185.

Lewis Hayden (Coffin, 1880)

Reference

Fairbank writes:--

I left for Kentucky about the 24th August, 1844, and taking time to learn the best route and become acquainted with reliable sources of aid, I arrived in Lexington, Kentucky, on the first of September. Miss Delia Webster was then teaching in Lexington. I examined into the case of Berry's wife, the slave woman, whom I had come to aid, but it seemed doubtful whether I could succeed in getting her away. In the meantime Miss Webster told me of a slave man named Lewis Hayden, his wife, and son of ten years, who were very anxious to escape, and I resolved to aid them. Interviews were held and arrangements made, and on the night of September 28th, Miss Webster and I, waiting in a hired hack near the residence of Cassius M. Clay, on the outer part of the city, were joined by Hayden and wife and son. At Millersburg, twenty-four miles distant, we were detained nearly an hour, having to obtain another horse in the place of one of ours, which failed; and while here we were recognized by two colored men from Lexington. On their return they unwittingly started the report which afterwards led to our arrest. At nine o'clock the next morning we crossed the river at Maysville, Kentucky, and were soon safe in Ripley, Ohio. I conducted the fugitives to a depot of the Underground Railroad, where they took passage and reached Canada in safety.

I left for Kentucky about the 24th August, 1844, and taking time to learn the best route and become acquainted with reliable sources of aid, I arrived in Lexington, Kentucky, on the first of September. Miss Delia Webster was then teaching in Lexington. I examined into the case of Berry's wife, the slave woman, whom I had come to aid, but it seemed doubtful whether I could succeed in getting her away. In the meantime Miss Webster told me of a slave man named Lewis Hayden, his wife, and son of ten years, who were very anxious to escape, and I resolved to aid them. Interviews were held and arrangements made, and on the night of September 28th, Miss Webster and I, waiting in a hired hack near the residence of Cassius M. Clay, on the outer part of the city, were joined by Hayden and wife and son. At Millersburg, twenty-four miles distant, we were detained nearly an hour, having to obtain another horse in the place of one of ours, which failed; and while here we were recognized by two colored men from Lexington. On their return they unwittingly started the report which afterwards led to our arrest. At nine o'clock the next morning we crossed the river at Maysville, Kentucky, and were soon safe in Ripley, Ohio. I conducted the fugitives to a depot of the Underground Railroad, where they took passage and reached Canada in safety.

Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1880), 719-20.

This work is the property of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It may be used freely by individuals for research, teaching and personal use as long as this statement of availability is included in the text.

This work is the property of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It may be used freely by individuals for research, teaching and personal use as long as this statement of availability is included in the text.

Lewis Hayden (National Park Service)

Reference

The Hayden’s routinely cared for self-emancipated African Americans at their home, which served as a boarding house. Records from the Boston Vigilance Committee, of which Lewis was a member, indicate that scores of people received aid and safe shelter at the Hayden home between 1850 and 1860. Lewis Hayden was one of the men who helped rescue Shadrach Minkins from federal custody in 1851 and he played a significant role in the attempted rescue of Anthony Burns. Hayden also contributed money to John Brown, in preparation for his raid on Harper’s Ferry.

William and Ellen Craft were among Lewis and Harriet Hayden’s most famous boarders. The Crafts had escaped from slavery by riding a passenger train to the north. Ellen, who was of light complexion, disguised herself as a southern gentleman and William played the role of a personal servant. The Crafts toured the United States, Canada, and Great Britain speaking against slavery, and they became celebrated public figures. While they were living and working in Boston, slave catchers were sent north to try to reclaim them. However, Lewis Hayden was determined to fight for their protection. Hayden threatened that two kegs of gun powder were kept near the entryway of his home. Should slave catchers come and attempt to reclaim their “property”, Hayden would sooner have blown up the house then surrender the Crafts. Eventually, the slave catchers were convinced to leave Boston.

William and Ellen Craft were among Lewis and Harriet Hayden’s most famous boarders. The Crafts had escaped from slavery by riding a passenger train to the north. Ellen, who was of light complexion, disguised herself as a southern gentleman and William played the role of a personal servant. The Crafts toured the United States, Canada, and Great Britain speaking against slavery, and they became celebrated public figures. While they were living and working in Boston, slave catchers were sent north to try to reclaim them. However, Lewis Hayden was determined to fight for their protection. Hayden threatened that two kegs of gun powder were kept near the entryway of his home. Should slave catchers come and attempt to reclaim their “property”, Hayden would sooner have blown up the house then surrender the Crafts. Eventually, the slave catchers were convinced to leave Boston.

National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, “Lewis and Harriet Hayden House,” Boston African American National Historic Site – Lewis and Harriet Hayden House. http://www.nps.gov/boaf/historyculture/lewis-and-harriet-hayden-house.html.