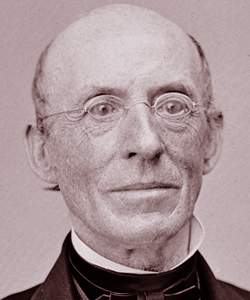

William Lloyd Garrison, American Anti-Slavery Society (American National Biography)

Scholarship

December 1833…leading northern abolitionists convened in Philadelphia to inaugurate the American Anti-Slavery Society. This organization was designed as a national body that would stimulate the creation of abolitionist societies across the North and win support for immediate emancipation. Its founding members, a profile of the larger crusade against slavery, included New York City religious evangelicals such as the Tappan brothers, Joshua Leavitt, and William Jay, Unitarian radicals such as Samuel Sewall and Samuel May, Quakers like John Greenleaf Whittier and Lucretia Mott, and free African Americans such as Robert Purvis and James McCrummell.

Garrison's contribution to the launching of this biracial, gender-inclusive organization was his authorship of the society's Declaration of Sentiments, which stressed nonviolence. While condemning the slaveholder as a "manstealer," the Declaration announced unshakable opposition to colonization, to all laws upholding slavery, and to all customs and attitudes that enforced racial prejudice…

To accomplish these formidable tasks, the Declaration also urged abolitionists to found newspapers and antislavery societies, launch petition campaigns, send speakers into the countryside, and challenge the moral sensibilities of slaveholders by appeals through the various religious denominations. Through this broad-based program of "moral suasion," as the abolitionists called it, the aim was peacefully to transform public opinion in favor of freeing the slaves and obliterating racial prejudice. While to most white Americans Garrison's Declaration reeked of fanaticism by proposing to transform three million slaves into equal citizens, to later generations it has come to represent a landmark of democratic aspiration.

Garrison's contribution to the launching of this biracial, gender-inclusive organization was his authorship of the society's Declaration of Sentiments, which stressed nonviolence. While condemning the slaveholder as a "manstealer," the Declaration announced unshakable opposition to colonization, to all laws upholding slavery, and to all customs and attitudes that enforced racial prejudice…

To accomplish these formidable tasks, the Declaration also urged abolitionists to found newspapers and antislavery societies, launch petition campaigns, send speakers into the countryside, and challenge the moral sensibilities of slaveholders by appeals through the various religious denominations. Through this broad-based program of "moral suasion," as the abolitionists called it, the aim was peacefully to transform public opinion in favor of freeing the slaves and obliterating racial prejudice. While to most white Americans Garrison's Declaration reeked of fanaticism by proposing to transform three million slaves into equal citizens, to later generations it has come to represent a landmark of democratic aspiration.

James Brewer Stewart, "Garrison, William Lloyd," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00256.html.

William Lloyd Garrison, "Garrisonianism" (American National Biography)

Scholarship

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, as the political crisis over slavery's westward expansion deepened, Garrison's espousals of northern disunion, nonresistance, woman's rights, and anticlericalism satisfied his own prophetic purity but left him and his supporters largely removed from the political events that were leading to civil war. At the same time, the term "Garrisonianism" also came to embody the most dangerous tendencies in Yankee political culture, not only for slaveholders but for those who valued the Union above all else. On 4 July 1854, when Garrison burned a copy of the U.S. Constitution, his flamboyant gesture only confirmed a generalized fear of New England extremism that had become commonplace in antebellum political culture. Only after John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859 did Garrison begin to retreat from his nonresistant positions, and only after Abraham Lincoln's election in 1860 did he begin to affirm that the Union deserved preserving in the face of southern moves toward secession.

James Brewer Stewart, "Garrison, William Lloyd," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00256.html.