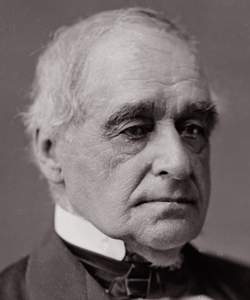

Hannibal Hamlin, Wilmot Proviso (American National Biography)

In 1843 Hamlin was elected to Congress, serving two terms in the House. Hamlin fought at John Quincy Adams's side to rescind the "gag rule," which barred abolitionist petitions from consideration by the House. He opposed Texas annexation on antislavery grounds and saw the Mexican War as a southern plot to expand the "peculiar institution." Hamlin helped formulate the Wilmot Proviso, which proposed to ban slavery from any territory acquired from Mexico.

Hannibal Hamlin, Senate Career (American National Biography)

In 1860 the Republican National Convention nominated Senator Hamlin for vice president. The former Democrat from Maine balanced nicely the former Whig from Illinois, and Hamlin was perceived as a supporter of William H. Seward (incorrectly, since he feared the N.Y. senator would lose the election), with many delegates eager to offer a consolation prize to the disappointed Sewardites.

Hannibal Hamlin (Congressional Biographical Directory)

Hannibal Hamlin (Dictionary of United States History)

Hannibal Hamlin (Notable Americans)

Hannibal Hamlin (New York Times)

BANGOR, Me., July 5, - The festivities of the night of Independence Day had just set in here when the intelligence of the death of ex-Vice President Hannibal Hamlin became known throughout the city. He died, as he has lived here for the past few years,, peacefully and quietly.

Mr. Hamlin was the President of the Tarratine Club of this city, to the rooms of which he had been wont to resort each afternoon to play at his favorite games of cards, whist, or pedro. He went there to-day, seemingly in his usual health, and about $:30 o’clock was seated at a table with F.W. Carr, Superintendent of the American Express, and Messrs. Strickland and Hight, all intimate friends. Several members were about the rooms, among them a leading physician. Quite elated at his success with the cards, Mr. Hamlin was in a happy frame of mind.

But suddenly his cards fell from his hands, his head dropping to the table. He said he was ill. At once a physician was at his side. Mr. Hamlin’s face was of a purple hue, the hands were clenched, and the mouth was firmly compressed. A dose o f brandy and ammonia was given him, which temporarily revived him, after which he became unconscious, remaining so for some time.

Later he regained his senses and speech. Gen. Charles Hamlin, his s on, told The Time’s representative he at first felt sure his father would recover, as he had previously experienced similar attacks, which were thought to be due to a combination of heart trouble and dyspepsia. As Gen. Hamlin stood by the couch where his father lay, he said:

“Father, we will place you upon the bed soon. You will lie there much better.”

“Very well,” was the answer.

“Are you comfortable now?”

“No, I am burning up.”

These were the last words of the dying man, save when, a few moments later, he complained of being hot, which the physician told him, was a good sign. Mr. Hamlin, with one of his characteristic smiles, said there was such a thing as a man being too warm. He did not speak after this, breathing his last quietly and seemingly without pain at 8:15 o’clock.

His wife and Gen. Hamlin and wife were present at the deathbed, and a few moments after he passed away another son arrived from Ellsworth, twenty-six miles away. There are two other sons, one in the West and one in New York.

Mr. Hamlin’s life has been very domestic since his retirement from public service. With his second wife, his junior by a number of years, he has lived quietly in his beautiful home here, taking great delight in agricultural pursuits. Save on two or three occasions, he has steadily declined to speak in public unless so requested by Grand Army posts, when he has always responded.

Frequently he has spoken of the “twilight of years” which were closing on him, and of the fact that his end was near, and has said that he stood ready to respond at the last great roll call.

At the request of The Time’s representative, some time since, he gave the following record of his service in public life: Representative o Legislature, 1836-40, and in 1847; Speaker of the House, 1837-9, and 1840; Aide de Camp to Gov. John Fairfield, 1839; Representative Twenty-eight and Twenty-ninth Congresses, 1843 to 1847; United States Senator, 1848 to 1856; Governor in 1857; United States Senator, 1857 to 1861; Vice President, 1861 to 1865; Collector, Port of Boston, 1865 t0 1866; United States Senator, 1869 to 1881; Minister to Spain, [illegible], resigned in 1883. The degree of LL. D. was conferred upon him by Colby University in 1869. He was a private in Company A, State Coast Guards, during the war and so served when not in Washington.

His last public utterances were on the occasion of the meeting of the Penobscot County Bar, two weeks ago, in memory of his personal friend, the late ex-Chief Justice John Appleton. Mr. Hamlin was the oldest member of the wedding of Recorder Perkins, last week, where he said he hoped to live to have a golden wedding of his own.

The death of Hannibal Hamlin closes a most picturesque and, at the same time, a typical American career, His life, as far as its real existence is concerned, was essentially a part of the history of generation that is past. His death, however, will be regarded with sorrow by young and old alike, for, though he ceased to play an active part in public life many years ago, yet he was, up to the day of his death, a figure wherever he appeared.

Hannibal Hamlin was born in 1809 in Paris, Me. He was a son of Dr. Cyrus Hamlin, and the family was one of the oldest in the Pine Tree State. The Hamlins originally belonged to the Massachusetts Colony. Hannibal’s grandfather had commanded a company of minute men in the Revolutionary war, and had five of his sons enrolled under him. Hannibal Hamlin’s mother was Anna Livermore, daughter of Deacon Elijah Livermore, proprietor of a township in the Androscoggin Valley.

Hannibal Hamlin was born with anything but a silver spoon in his mouth. The family, while rich in ancestral blood, was poor in worldly goods, and the boy was given to understand at a very early age that he must shift for himself. As a boy he seemed to appreciate this, and consequently he trained himself to be what he always was – a hard worker. At the district school, and afterward at the Hebron Academy, he always strived to rank first, and he generally did. At the same time he was a prince among good fellows, always ready for a lark and equally ready to take his share of the consequences. As a boy his independence was marked. He knew what he should have and what he should not. He insisted on the former and cheerfully resigned the latter. Stories illustrating this phase of his early life are numerous, and in Maine are told and appreciated to this day.

Those who knew young Hannibal Hamlin predicted that he was “cut out for the law.” His father had intended to give him a college training, and when entering upon his sixteenth year he w as ready to enter a university. At that time, however, his brother Cyrus, who was to have conducted the farm at home, broke down physically, so Hannibal had to stuck to the farm while his brother went to study medicine. Suffice it to say that the boy went at this uncongenial work with the same willing spirit that he went at all his tasks. For a year he worked on the farm. Then he varied the monotony of that life and earned the first money he ever earned for himself by teaching school.

With the aid of the money thus earned he began to study law with his big brother Elijah. He was then eighteen years old, physically and mentally a splendid youth. He entered upon the study of law with a zest that augured success. Less than a year after, the unexpected death of his father made it imperative upon him to give up his chosen work and go back to the farm to provide for his mother. Much as he felt the blow, he went back cheerfully and for two years lived on and worked the homestead property.

Engaged in this labor of love, he was all the time impelled by his nature to seek a sphere of usefulness that would bring him into contact with a more active life and with freer thought. The result of his longing was the purchase by him, in partnership with Horatio King, of the Jeffersonian, a weekly political newspaper published in Oxford County. While connected with this paper he learned to set type, and was proud of the fact that all his contributions to it were set “hot from the brain,” or by himself, without manuscript.

He gave up the newspaper to go back to the law. He studied with Joseph B. Cole for three years, and afterward with Fessenden, Deblois & Fessenden of Portland. In 1833, he then being twenty-four years old, he was admitted to the bar. On the same day, singularly enough, he won his first law case. He married Judge Emery’s daughter a few months after, and many years later made another of Judge Emery’s daughters his second wife.

During his early life Hamlin apparently had no thoughts of a political career, yet he took a keen interest in political doings. Though the Hamlins were Whigs, he became an ardent Democrat. Just after his first marriage he moved to the town of Hampden, near Bangor. There he soon acquired a reputation as a shrewd lawyer and a strong speaker on all public questions. In 1836 the Democrats sent him to the State Legislature in Hampden and he was kept there for five terms. For three of these he was chosen Speaker almost without opposition.

In 1840, in the height of the great excitement attending the Harrison campaign, Hamlin received the Democratic nomination for Congress from the Penobscot district. Even at that early date Maine was considering the slavery question, and upon it Hamlin held most advanced views, which he did not hesitate to express. In the Harrison tornado, that then overthrew Democratic rule, Hamlin fell, but only by a defeat of a 200 majority. In the succeeding elections he was triumphant.

The first trip to Washington made by the newly-elected member was noticeable for the varied character of the conveyances in which it was accomplished. From his home Mr. Hamlin traveled to Portland by stagecoach, from Portland he went to Boston by boat, then to Norwich by rail, from the latter place he crossed the Sound to Greenport, from there took the Long Island Railroad to New York, from the latter place he again took the railway to Philadelphia, from that point made the best of his way by boat and stagecoach to Baltimore, and from the Monumental City at last reached the capital by rail. Arriving in Washington after this tedious journey, he found it to be a straggling, dilapidated, and overgrown village of less than 20,000 inhabitants. The streets of magnificent houses which now accommodate the two hundred and odd thousand residents of the place were then utilized as cow pastures.

Hamlin’s ability and appearance, which was very striking, soon advanced him to a prominent position in the capital. At the start he stated that he was unequivocally opposed to slavery. A speech on this question made John Quincy Adams his staunch friend. Hamlin fought every measure which he regarded as tending toward an extension of slavery, as, for instance, the annexation of Texas. Hamlin was re-elected to Congress by an overwhelming majority.

It was during his second term that the Wilmot proviso came up. Hamlin took such a stand then on the slavery question as to place himself in practically beyond the control of his own organization. Returning to Maine at the close of that, the Twenty-ninth Congress, he was sent to the State Legislature, which that year had to vote for a United States Senator. Hamlin became a candidate. He was defeated by one vote.

In 1847 Gov. Fairfield, the then senior Senator from Maine, died. Hamlin again became a candidate for the honor. He was elected, largely by the aid of the Free-Soil Party. In the Senate he stood by his radical views against slavery, obnoxious as they were to his party leaders. He continued a Senator and acted with the Democratic Party up to 1856. Then he left it. Before doing so he made a speech that became famous, stating to his colleagues in the Senate that the party was not in harmony with him on the then great question – slavery. From that time forward Mr. Hamlin acted with the then insignificant Republican Party.

Soon after his withdrawal from the Democratic Party he was nominated by the Republicans for Governor of Maine. There was apparently no prospect of his election. With all the energy and force characteristic of him, however, he entered into the campaign. He talked anti-slavery from one end of Maine to the other. He was elected by a majority of 18,000 votes over two competitors, twice more than Maine had ever given to a candidate for Governorship.

The result of his election was greatly to encourage the supporters of Fremont in the national struggle that followed. Mr. Hamlin had served but a few days as Governor when he was elected Senator for the third time. He resigned the Governorship and returned to his seat in Congress. There he stood sturdily by anti-slavery, his speeches on the great legislative measures of that day attracting widespread attention.

But prominent as was Mr. Hamlin’s figure in the Senate he was destined to a more prominent position before the people. In the midst of a political excitement which had never before been equaled in the United States, the National Republican Convention to nominate a President and a Vice President met in Chicago in 1860. The eyes of the country were on that convention. Abraham Lincoln was nominated for the head of the ticket over five other candidates. Hannibal Hamlin was nominated for the Vice Presidency, but yielded to the persuasions of his friends.

Of the campaign which followed the nomination of Lincoln and Hamlin, and the exciting discussions which grew out of the nomination, and ultimately resulted in the great civil war, it is not necessary to speak in this place. It may, however, be said, in contradiction of statements which have been made, that the campaign, so far as Abraham Lincoln, Hannibal Hamlin, and their immediate friends and supporters were concerned, was fought entirely on the principle of the non-extension, not the abrogation, of the institution of slavery. Mr. Hamlin, at least, had never, up to this time, been one of those who wished to precipitated conflict by interfering with what might be called the established rights of the South. Still he was most sought everywhere and an aviation given him where he went. Since 1887 he has been seen little on public occasions. He appeared at a banquet given in this city last Winter. It was a sort of Republican jubilee. He arose to speak. For a minute or two he was eloquent. Then his strength seemed to give out, his voice failed, and he sat down. His first statement on that occasion was that he believed that he was making his last public speech.