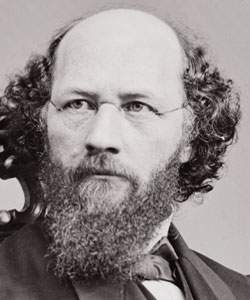

Stephen Johnson Field (American National Biography)

Scholarship

Field's legacy is a tribute to his persistence. He labored in the minority through much of his career; many of his most important and innovative theories of law were expressed as dissenting or concurring opinions. By the 1890s, however, the majority of the court had adopted much of his doctrine and held to it after his death. The adoption of liberty-of-contract doctrine in Allgeyer and Lochner provides the most obvious example, but Field's ideas also lived on in Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway Company v. Minnesota (1890) and Smyth v. Ames (1898), which, in keeping with his Munn dissent, recognized that rate regulation could violate the due process guarantee. His opposition to class legislation and the spirit of his Santa Clara and San Mateo opinions were later reflected when the Supreme Court overruled the federal income tax in Pollock v. Farmers Loan and Trust (1895).

Field resigned from the Court on 1 December 1897. He died at his home in Washington, D.C. He had spent a record thirty-four years on the Court, outlasting eight presidents and three chief justices. More importantly, he set the stage for laissez-faire constitutionalism. For nearly four decades following Field's death, a narrow majority of the Supreme Court vigorously applied most of the legal doctrine he had pioneered. His vision of entrepreneurial liberty dominated constitutional doctrine until its clash with Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal produced a backlash in 1937.

Field resigned from the Court on 1 December 1897. He died at his home in Washington, D.C. He had spent a record thirty-four years on the Court, outlasting eight presidents and three chief justices. More importantly, he set the stage for laissez-faire constitutionalism. For nearly four decades following Field's death, a narrow majority of the Supreme Court vigorously applied most of the legal doctrine he had pioneered. His vision of entrepreneurial liberty dominated constitutional doctrine until its clash with Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal produced a backlash in 1937.

Paul Kens, "Field, Stephen Johnson," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/11/11-00299.html.