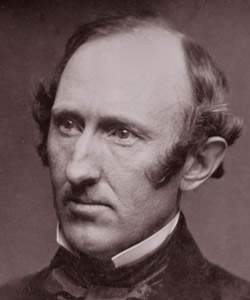

Wendell Phillips, Abolition and the Civil War (American National Biography)

Scholarship

In the years immediately before the Civil War Phillips's oratory, not his labors for the American Anti-Slavery Society, defined his greatest significance. As the sectional crisis ran its course, he fashioned speeches that dramatized the moral imperative facing the North: people must confront the South and destroy slavery. Collected in books and widely reprinted in newspapers, Phillips's speeches, particularly those urging defiance of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, supporting free-soil struggles in Kansas, and praising John Brown's invasion of Harpers Ferry, gave Yankee political culture a strain of egalitarian extremism that presaged a war for slave emancipation.

The onset of the war itself magnified Phillips's stature and influence as "abolition's golden trumpet." Discarding his disunionism, he declared secession to be treason and demanded war aims that would free the slaves, cede them their former masters' lands, grant them full civil rights, furnish them with free public education, and guarantee them full manhood suffrage. Joining other Radical Republicans, Phillips grew increasingly critical of President Abraham Lincoln's reluctance to prosecute a forthright war of slave liberation, a posture that put him much at odds with Garrison and many other Lincoln supporters within the American Anti-Slavery Society.

The onset of the war itself magnified Phillips's stature and influence as "abolition's golden trumpet." Discarding his disunionism, he declared secession to be treason and demanded war aims that would free the slaves, cede them their former masters' lands, grant them full civil rights, furnish them with free public education, and guarantee them full manhood suffrage. Joining other Radical Republicans, Phillips grew increasingly critical of President Abraham Lincoln's reluctance to prosecute a forthright war of slave liberation, a posture that put him much at odds with Garrison and many other Lincoln supporters within the American Anti-Slavery Society.

James Brewer Stewart, "Phillips, Wendell," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00548.html.

Wendell Phillips, Reconstruction (American National Biography)

Scholarship

The Garrisonians, moreover, did not share Phillips's vision of a radically reconstructed South, and debates over these questions finally fractured the abolitionist movement. After the passage in 1865 of the Thirteenth Amendment, freeing all slaves, Garrison and his supporters declared the abolitionists' crusade a success, retired, and left Phillips as president of a much depleted American Anti-Slavery Society. For the next five years, until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, Phillips put nearly all of his energies into the struggle for black equality, speaking and writing on the imperative of guaranteeing former slaves the full rights and the protections of citizenship. With the passage of that amendment, Phillips finally conceded that there was little else he could do to help secure the future of African Americans living in the old Confederacy.

James Brewer Stewart, "Phillips, Wendell," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00548.html.