Record Data

Source citation

Lillian Foster, Andrew Johnson, Andrew Johnson, President of the United States; His Life and Speeches (New York: Richardson and Company, 1866), 242-261.

Type

Speech

Date Certainty

Exact

Transcriber

John Osborne, Dickinson College

Transcription date

Transcription

The following text is presented here in complete form, as it originally appeared in print. Spelling and typographical errors have been preserved as in the original.

Fellow-Citizens — for I presume I have the right to address you as such — to the committee who have conducted and organized this meeting so far, I have to render my sincere thanks for the compliments and approbation they have manifested in their personal address to myself, and in the resolutions they have adopted. Fellow-citizens — I was about to tender my thanks to the committee who waited upon me and presented me with the resolutions adopted on this occasion — resolutions, as I understand, complimentary to the policy pursued by this administration since it came into power. I am free to say to you on this occasion, that it is extremely gratifying to me to know that so large a portion of my fellow-citizens approve and indorse the policy that has been adopted, and is intended to be carried out. (Applause.) That policy has been one which was intended to restore the glorious union of these States and their original relations to the government of the United States. (Prolonged applause.) This seems to be a day peculiarly appropriate for such a manifestation — the day that gave birth to him who founded this Government — the Father of his Country ; of him who stood at the head of the government when all the States entered into the Union. This day, I say, is peculiarly appropriate to indorse therestoration of the Union of these States founded by the Father of his Country. Washington, whose name this city bears, is embalmed in the hearts of all who love free government. (A voice — "So is Andrew Johnson") Washington, who, in the language of his eulogists, was " First in peace, first in war, first in the hearts of his countrymen." No people can claim him ; no nation can appropriate him ; his reputation and life are the common inheritance of all who love free government.

I to-day had the pleasure of attending the National Washington Monument Association, which is directing its efforts to complete the monument erected to his memory. I was glad to meet them, and, so far as I could, to give them my humble influence. A monument is being erected to him within a stone's throw of the spot from which I address you. Let it be completed. (Cheers.) Let the pledges which all these States, associations, and corporations have placed in that monument of their faith and love for this Union be preserved. Let it be completed, and in this connection let me refer to the motto upon the stone sent from my own State. God bless (A voice — " And bless you") a State which has struggled for the preservation of the Union, in the field and in the councils of the nation, and is now struggling in consequence of the interruption that has taken place in her relations with the Federal Government, growing out of the rebellion, but struggling to recover those relations and take her stand where she has stood since 1796. A motto is inscribed on that stone sent here to be placed in that monument of freedom and in commemoration of Washington. I stand by that sentiment, and she is willing to stand by it. It was the sentiment enunciated by the immortal Andrew Jackson, "The Federal Union — it must be preserved." (Wild shouts of applause.) Were it possible to have the great man whose statue is now before me, and whose portrait is behind me in the Capitol, and whose sentiment is inscribed on the stone deposited in the monument — were it possible to communicate with the illustrious dead, and he could be informed of or made to understand the working or progress of faction, rebellion, and treason, the bones of the old man would stir in their coffin, and he would rise and shake off the habiliments of the tomb ; he would extend that long arm and finger of his, and he would reiterate that glorious sentiment, "The Federal Union — it must be preserved." (Applause.) But we see and witness what has transpired since his day? We remember what he did in 1833, when treason, treachery, and infidelity to the Government and Constitution of the United States then stalked forth. It was his power and influence that then crushed the treason in its infancy. It was then stopped : but only for a time — the spirit continued. There were men disaffected to the Government both North and South. We had peculiar institutions, of which some complained and to which others were attached. One portion of our countrymen advocated that institution in the South ; another opposed it in the North ; and it resulted in creating- two extremes. The one in the South reached the point at which they were prepared to dissolve the Government of the United States, to secure and preserve their peculiar institution; and in what I may say on this occasion I want to be understood.

There was another portion of our countrymen who were opposed to this peculiar institution in the South, and who went to the extreme of being willing to break up the Government to get clear of it. [Applause.] I am talking to you to-day in thecommon phrase, and assume to be nothing but a citizen, and one who has been fighting for the Constitution and to preserve the Government. These two parties have been arrayed against each other ; and I stand before you to-day, as I did in the Senate in 1860, in the presence of those who were making war on the Constitution, and who wanted to disrupt the Government, to denounce, as I then did in my place, those who were so engaged, as traitors. I have never ceased to repeat, and so far as my efforts could go, to carry out, the sentiments I then uttered. [Cheers.] I have already remarked that there were two parties, one for destroying the Government to preserve slavery, and the other to break up the Government to destroy slavery. The objects to be accomplished were different, it is true, so far as slavery is concerned, but they agreed in one thing, and that was the breaking up of the Government. They agreed in the destruction of the Government, the precise thing which I have stood up to oppose. Whether the disunionists come from the South or the North I stand now where I did then, to vindicate the Union of these States and the Constitution of the country. [Applause.]

The rebellion or treason manifested itself in the South. I stood by the Government. I said I was for the Union with slavery, or I was for the Union without slavery. In either alternative, I was for my Government and the Constitution. [Applause.] The Government has stretched forth its strong arm, and with its physical power has put down treason in the field. Yes, the section of country which has arrayed itself against the Government has been put down by the Government itself. Now, what do these people say? We said, "No compromise; we can settle this question with the South in eight and forty hours." How ? "Disband your armies, acknowledge the Constitution of the United States, obey the law, and the whole question is settled." Well, their armies have been disbanded. They come forward now in a spirit of magnanimity and say, "We were mistaken; we made an effort to carry out the doctrine of secession and dissolve the Union, but we have failed; and, having traced this thing to a logical and physical consequence and result, we now again come forward and acknowledge the flag of our country, obedient to the Constitution and the supremacy of the law." [Cheers.] I say, then, when you have yielded to the law, when you acknowledge your allegiance to the Government, I am ready to open the doors of the Union and restore you to your old relations to the Government of our fathers. [Prolonged applause.]

Who, I ask, has suffered more for the Union than I have ? I shall not now repeat the wrongs or suffering inflicted upon me; but it is not the way to deal with a whole people in the spirit of revenge. I know much has been said about the exercise of the pardoning power, so far as the Executive power is concerned. There is no one who has labored harder than I have to have the principal conscious and intelligent traitors brought to justice ; to have the law vindicated, and the great fact vindicated that treason is a crime. Yet, while conscious, intelligent traitors are to be punished, should whole States, communities, and people be made to submit to and bear the penalty of death? I have, perhaps, as much hostility and as much resentment as a man ought to have ; but we should conform our action and our conduct to the example of Him who founded our holy religion— not that I would liken this to it or bring any comparison, for I am not going to detain you long.

But, gentlemen, I came into power under the Constitution of the country and by the approbation of the people. And what did I find? I found eight millions of people who were in fact condemned under the law — and the penalty was death. Under the idea of revenge and resentment, they were to be annihilated and destroyed. Oh, how different this from the example set by the holy Founder of our religion, whose divine arm touches the horizon and embraces the whole earth! Yes, He who founded this great scheme came into the world and found our race condemned under the law — and the sentence was death. What was his example? Instead of putting the world or a nation to death. He went forth with grace and attested by His blood and His wounds that He would die and let the nation live. [Applause.] Let them become loyal and willing supporters and defenders of our glorious Stripes and Stars and the Constitution of our country. Let their leaders, the conscious, intelligent traitors, suffer the penalty of the law, but for the great mass who have been forced into this rebellion and misled by their leaders, I say leniency, kindness, trust, and confidence. [Enthusiastic cheers.]

But, my countrymen, after having passed through the rebellion and given such evidence as I have — though men croak a great deal about it now — (laughter) when I look back through the battle-fields and see many of those brave men, in whose company I was in part of the rebellion where it was most difficult and doubtful to be found; before the smoke of battle has scarcely passed away; before the blood shed has scarcely congealed, whhat do we find? The rebellion is put down by the strong arm of the Government in the field; but is if the only way in which we can have rebellion? They struggled for the breaking up of the Government, but before they are scarcely out of the battle-field, and before our brave men have scarcely returned to their homes to renew the ties of affection and love, we find ourselves almost in the midst of another rebellion. [Applause.] The war to suppress our rebellion was to prevent the separation of the States, and thereby change the character of the Government and weakening its power. Now, what is the change? There is an attempt to concentrate the power of the Government in the hands of a few, and thereby bring about a consolidation, which is equally dangerous and objectionable with separation. [Enthusiastic applause.] We find that powers are assumed and attempted to be exercised of a most extraordinary character. What are they? We find that Government can be revolutionized, can be changed without going into the battle-field. Sometimes revolutions the most disastrous to the people are effected without shedding blood. The substance of our Government may be taken away, leaving only the form and shadow. Now, what are the attempts? What is being proposed?

We find that, in fact, by an irresponsible central directory, nearly all the powers of Government are assumed without even consulting the legislative or executive departments of the Government. Yes, and by resolution reported by a committee upon whom all the legislative power of the Government has been conferred, that principle in the Constitution which authorizes and empowers each branch of the legislative department to be judges of the election and qualifications of its own members, has been virtually taken away from those departments and conferred upon a committee, who must report before they can act under the Constitution and allow members duly elected to take their seats. By this rule they assume that there must be laws passed; that there must be recognition in respect to a State in the Union, with all its practical relations restored, before the respective houses of Congress, under the Constitution, shall judge of the election and qualifications of its own members. What position is that? You have been struggling for four years to put down the rebellion. You denied in the beginning of the struggle that any State had the right to go out. You said that they had neither the right nor the power. The issue has been made, and it has been settled that a State has neither the right nor the power to go out of the Union. And when you have settled that by the executive and military power of the Government, and by the public judgment, you turn around and assume that they are out and shall not come in. [Laughter and cheers.]

I am free to say to you, as your Executive, that I am not prepared to take any such position. I said in the Senate, at the very inception of the rebellion, that States had no right to go out and tliat they had no power to go out. That question has been settled. And I cannot turn round now and give the direct lie to all I profess to have done in the last five years [Laughter and applause.] I can do no such thing. I say that when these States comply with the Constitution, when they have given sufficient evidence of their loyalty, and that they can be trusted, when they yield obedience to the law, I say, extend to them the right hand of fellowship and let peace and union be restored. [Loud cheers] I have fought traitors and treason in the South; I opposed the Davises and names I need not repeat; and now, when I turn round at the other end of the line, I find men - I care not by what name you call them - [A voice, "Call them traitors"], who still stand opposed to the restoration of the Union of these States. And I am free to say to you that I am still in favor of this compact; I am still for the restoration of this Union; I am still in favor of this great Government of ours going on and following out its destiny. [A voice "Give us the names."]

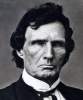

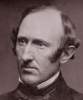

A gentleman calls for their names. Well, suppose I should give them. [A voice, "We know them"] I look upon them - I repeat it, as President or citizen - as being as much opposed to the fundamental principles of this Government, and believe they are as much laboring to pervert or destroy them as were the men who fought against us. [A voice, "What are the names?"] I say Thaddeus Stevens, of Pennsylvania - [tremendous applause] - I say Charles Sumner- [great applause]- I say Wendell Phillips, and others of the same stripe, are among them. [A voice, "Give it to Forney."] Some gentleman in the crowd says "Give it to Forney." I have only just to say that I do not waste my ammunition upon dead ducks. [Laughter and applause.]

I stand for my country, I stand for the Constitution, where I placed my feet from my entrance into public life. They may traduce me, they may slander me, they may vituperate; but let me say to you that it has no effect upon me. [Cheers.] And let me say in addition, that I do not intend to be bullied by my enemies. [Applause, and a cry, "The people will sustain you."] I know, my countrymen, that it has been insinuated, and not only insinuated, but said directly — the intimation has been given in high places — that if such a usurpation of power had been exercised two hundred years ago in a particular reign it would have cost a certain individual his head. What usurpation has Andrew Johnson been guilty of? ["None, none."] The usurpation I have been guilty of has always been standing between the people and the encroachments of power. And because I dared to say in a conversation with a fellow-citizen, and a senator too, that I thought amendments to the Constitution ought not to be so frequent; that their effect would be that it would lose all its dignity; that the old instrument would be lost sight of in a short time; because I happened to say that if it was amended such and such amendments should be adopted — it was a usurpation of power that would have cost a king his head at a certain time. [Laughter and applause.] And in connection with this subject it was explained by the same gentleman that we were in the midst of an earthquake, that he trembled and could not yield. [Laughter.] Yes, there is an earthquake coming. There is a ground-swell coming of popular judgment and indignation. ["That's true."] The American people will speak by their interests, and they will know who are their friends and who their enemies. What positions have I held under this government? Beginning with an alderman and running through all branches of the Legislature. [A voice — "From a tailor up.") Some gentleman says I have been a tailor. [Tremendous applause.] Now, that did not discomfit me in the least; for when I used to be a tailor I had the reputation of being a good one, and making close fits — [great laughter] — always punctual with my customers, and always did good work. [A voice — "No patchwork."] No, I do not want any patchwork. I want a whole suit. But I will pass by this little facetiousness. My friends may say you are President, and you must not talk about such things. When principles are involved, my countrymen, when the existence of my country is imperilled, I will act as I did on former occasions, and speak what I think. I was saying that I had held nearly all positions, from alderman, through both branches of Congress, to that which I now occupy, and who is there that will say that Andrew Johnson ever made a pledge that he did not redeem, or made a promise he did not fulfil? Who will say that he has ever acted otherwise than in fidelity to the great mass of the American people? They may talk about beheading and usurpation ; but when I am beheaded I want the American people to witness I do not want by inuendoes, by indirect marks in high places, to see the man who has assassination brooding in his bosom, exclaim, "This presidential obstacle must be gotten out of the way." I make use of a very strong expression when I say that I have no doubt the intention was to incite assassination, and so get out of the way the obstacle from place and power. Whether by assassination or not, there are individuals in this Government, I doubt not, who want to destroy our institutions and change the character of the Government. Are they not satisfied with the blood which has been shed ? Does not the murder of Lincoln appease the vengeance and wrath of the opponents of this Government? Are they still unslaked? Do they still want more blood? Have they not got honor and courage enough to attain their object otherwise than by the hands of the assassin? No, no ; I am not afraid of assassins attacking me where a brave and courageous man would attack another. I only dread him when he would go in disguise, his footsteps noiseless. If it is blood they want, let them have courage enoughto strike like men. I know they are willing to wound, but they are afraid to strike. [Applause.] If my blood is to be shed because I vindicate the Union and the preservation of this Government in its original purity and character, let it be shed; let an altar to the Union be erected, and then, if it is necessary, take me and lay me upon it, and the blood that now warms and animates my existence shall be poured out as a fit libation to the Union of these States. [Great applause.] But let the opponents of this Government remember that when it is poured out, "the blood of the martyrs will be the seed of the Church." [Cheers.] Gentlemen, this Union will grow — it will continue to increase in strength and power, though it may be cemented and cleansed in blood. I have talked longer now than I intended. Let me thank you for the honor you have done me.

So far as this Government is concerned, let me say one word in reference to the amendments to the Constitution of the United States. When I reached Washington for the purpose of being inaugurated as Vice-President of the United States I had a conversation with Mr. Lincoln. We were talking about the condition of affairs and in reference to matters in my own State. I said that we had called a convention, had amended our Constitution by abolishing slavery in the State — a State not embraced in his proclamation. All this met his approbation and gave him encouragement, and in talking upon the amendment to the Constitution, he said : "When the amendment to the Constitution is adopted by three-fourths of the States, we shall have all, or pretty nearly all. I am in favor of amending the Constitution, if there was one other adopted.' Said I, "What is that, Mr. President?" Said he, "I have labored to preserve this Union. I have toiled four years; I have been subjected to calumny and misrepresentation, yet my great desire has been to preserve the Union of these States intact under the Constitution as they were before." "But," said I, "Mr. President, what amendment do you refer to?" He said he thought there should be an amendment to the Constitution which would compel all the States to send their Senators and Representatives to the Congress of the United States. Yes, compel them. The idea was in his mind that it was a part of the doctrine of secession to break up the Government by States withdrawing their Senators and Representatives from Congress; and, therefore, he desired a Constitutional amendment to compel them to be sent.

How now does the matter stand ? In the Constitution of the country, even that portion of it which provides for the amendment of the organic law, says that no State shall, without its consent, be deprived of its representation in the Senate. And now what do we find? We find the position taken that States shall not be represented; that we may impose taxes; that we may send our tax-gatherers to every region and portion of a State; that the people are to be oppressed with taxes; but when they come here to participate in legislation of the country, they are met at the door, and told, - "No! You must pay your taxes; you must bear the burdens of the Government; but you must not participate in the legislation of the country, which is to affect you for all time." Is this just? ["No, no."] Then, I say, let us admit into the councils of the nation those who are unmistakably and unequivocally loyal — those men who acknowledge their allegiance to the Government and swear to support the Constitution. It is all embraced in that. The amplification of an oath makes no difference, if a man is not loyal. But you may adopt whatever test oath you please to prove their loyalty. That is a matter of detail for which I care nothing. Let him be unquestionably loyal, owing his allegiance to the Government and willing to support it in its hour of peril and of need, and I am willing to trust him. I know that some do not attach so much importance to this principle as I do. But one principle we carried through. The Revolution was fought that there should be no taxation without representation. I hold to that principle, laid down as fundamental by our fathers. If it was good then, it is now. If it was a rule to stand by then, it is a rule to stand by now. It is a fundamental principle that should be adhered to as long as governments last.

I know it was said by some during the rebellion that our Constitution had been rolled up as a piece of parchment and laid away; that in the time of war and rebellion there was no Constitution. Well, we know that sometimes, from the very great necessity of the case, from a great emergency, we must do unconstitutional things in order to preserve the Constitution itself. But if, while the rebellion was going on, the Constitution was rolled up as a piece of parchment; if it was violated in some particular to save the Government, there may have been some excuse to justify it: but now that peace has come, now the war is over, we want a written Constitution, and I say the time has come to take the Constitution down, unroll it, read it, and understand its provisions. Now, if you have saved the Government by violating the Constitution in war, you can only save it in peace by preserving the Constitution of our fathers as it is now unfolded. It must now be read and understood by the American people. I come here to-day, as far as I can in making these remarks, to vindicate the Constitution and to save it, for it does seem to me that encroachment after encroachment is proposed. I stand to-day prepared, as far as I can, to resist these encroachments upon the Constitution and Government. Now that we have peace, let us enforce the Constitution; let us live under and by its provisions; let it be published; let it be printed in blazing characters, as if it were in the heavens, punctuated with stars, that all may read and understand ; let us consult that instrument; let us digest its provisions, understand them, and, understanding, abide by them. I tell the opponents of the Government, I care not from what quarter they come — whether from the East, West, North, or South, you who are engaged in the work of breaking up the Government by amendments to the Constitution, that the principles of free government, all deeply rooted in the American heart, all the powers combined, I care not of what character they are, cannot destroy that great instrument, that great chart of freedom. They may seem to succeed for a time; but their attempts will be futile. They might as well undertake to lock up the winds or chain the waves of the ocean and confine them to limits. They may think now it can be done by a concurrent resolution; but when it is submitted to the popular judgment and to the popular will, they will find that they might as well introduce a resolution to repeal the laws of gravity as to keep this Union from being restored. It is just about as feasible to resist the great law of gravity, which binds all to a common centre, as that great law which will bring back these States to their regular relations with the Union. All these conspiracies and machinations, North and South, I cannot prevent. All that is wanted is time, until the American people can get to see what is going on. I would the whole American people could be assembled here to-day, as you are. I wish we had an amphitheatre capacious enough to hold these thirty millions of people, that they could be here and witness the struggle that is going on to preserve the Constitution of their fathers. They would settle this question. They could see who it is, and how and what kind of spirit is breaking up this free Government. Yes, when they come to see the struggle and understand who is for and who against them, if you could make them perform the part of gladiators, in the first tilt you would find the enemies of the country crushed and helpless.

I have detained you longer than I intended. [Voices, "Go on."] We are in a great struggle. I am your instrument. Who is there I have not toiled and labored for? Where is the man or woman, either in public or private life, who has not always received my attention or my time? Pardon the egotism. They say that man Johnson is a lucky man, that no man can defeat me. I will tell you what constitutes luck. It is due to right, and being for the people ; that is what constitutes good luck. Somehow or other the people will find out and understand who is for and who is against them. I have been placed in as many trying positions as any mortal man was ever placed in, but so far I have not deserted the people, and I believe they will not desert me. What principle have I violated? What sentiments have I swerved from? Can they put their finger upon it? Have you heard of them pointing out any discrepancy? Have you heard them quote my predecessor, who fell a martyr to his country's cause, as going in opposition or in contradistinction to any thing that I have done? The very policy which I am pursuing now was pursued under his administration — was being pursued by him when that inscrutable Providence saw fit to summon him, I trust, to a better world. Where is there one principle adopted by him in reference to this restoration that I have departed from. ["None, none."] The war, then, is not simply upon me, but upon my predecessor. I have tried to do my duty. I know that some people, in their jealousy, have made the remark that the White House is President. Just let me say that the charms of the White House and all that sort of flummery has less influence with me than with those who are talking about it. The little I eat or wear does not amount to much. That required to sustain me and my little family is very little, for I am not feeding many, though in one sense of consanguinity I am akin to everybody. The conscious satisfaction of having performed my duty to my country is all the reward I have.

Then, in conclusion, let me ask this vast concourse, this sea of upturned faces, to join with me in standing round the Constitution of our country. It is again unfolded and the people are invited to read, to understand, and to maintain its provisions. Let us stand by the Constitution of our fathers, though the heavens themselves may fall. Let us stand by it, though faction may rage. Though taunts and jeers may come, though vituperation may come in its most violent character, I will be found standing by the Constitution as the chief rock of our safety, as the palladium of our civil and religious liberty. Yes, let us cling to it as the mariner clings to his last plank when night and tempest close around him. Accept my thanks for the indulgence you have given me in making the extemporaneous remarks I have upon this occasion. Let us go forward, forgetting the past and looking to the future, and try to restore our country. Trusting in Him who rules on high that ere long our Union will be restored, and that we will have peace, not only on earth, but especially with the people of the United States, and good-will, I thank you, my countrymen, for the spirit you have manifested on this occasion. When your country is gone, and you are about, look out and you will find the humble individual who now stands before you weeping over its final dissolution.