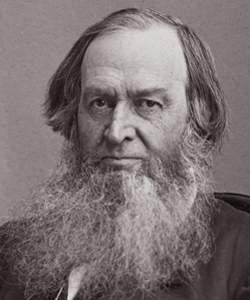

Gerrit Smith (Congressional Biographical Directory)

Reference

SMITH, Gerrit, a Representative from New York; born in Utica, N.Y., March 6, 1797; moved to Peterboro in 1806; attended an academy in Clinton, N.Y.; was graduated from Hamilton College, Clinton, N.Y., in 1818; studied law; engaged in the management of a large estate which he inherited; delegate to the State conventions in 1824 and 1828; unsuccessful Liberty Party candidate for governor in 1840; unsuccessful presidential candidate in 1848; was admitted to the bar in 1853 and commenced practice in Peterboro, N.Y.; elected as a Free-Soil candidate to the Thirty-third Congress and served from March 4, 1853, until August 7, 1854, when he resigned; resumed the practice of his profession, and was a publicist and philanthropist; he revived the Anti-Dramshop Party, but was a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1872 and supported Grant; died in New York City December 28, 1874; interment in Peterboro Cemetery, Peterboro, Madison County, N.Y.

“Smith, Gerrit,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774 to Present, http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=S000542.

Gerrit Smith (Stauffer, 2002)

Scholarship

When [Gerrit] Smith read the news of the raid and the actual results of his prophecy, he suffered a blow from which he never recovered. Seventeen men had been killed in battle, and [John] Brown and four surviving comrades had been captured and were almost certain to hang. And Smith’s own name was intimately linked to these deaths. He was far more sensitive and uncomfortable about the use (and sight) of bloodshed than were his co-conspirators, and more self-critical and introspective. To be sure, he had advocated violence in Kansas and had helped to fund it. But in that instance his violent means had yielded noble ends, for in his mind Kansas had been “saved” from slavery. Now violent action had brought failure, destruction, and death. And as he looked at what he had wrought, something snapped within him. The break affected him both outwardly and inwardly. The outward signs of the blow were noticeable immediately but subsided over time. The internal effects accrued slowly, almost without Gerrit’s knowing it; they did not show themselves for some time, but when they did, the change was profound.

John Stauffer, The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 242-243.

Gerrit Smith, Philanthropy (American National Biography)

Scholarship

The Smith family fortune was threatened by the nationwide financial depression of the late 1830s, but Gerrit ultimately survived the crisis richer than ever. In the 1840s and 1850s his annual income from his landholdings and investments in banking and railroads typically exceeded $60,000.

Smith's great fortune allowed him to become one of the leading philanthropists of the early nineteenth century. Although he was antisectarian in his personal religious beliefs, Smith gave generously to the American Bible Society, the American Tract Society, and the American Sunday School Union….Smith became a leader and major financial sponsor of state and national organizations promoting temperance, prison reform, international peace, and land reform. He also supported his wife's and his daughter Elizabeth Smith Miller's active participation in the women's rights movement.

The cause that captured the greatest portion of Smith's attention was the campaign to end slavery. At first Smith supported efforts to colonize slaves in Africa, but in 1835 he joined the more militant abolitionist movement that demanded immediate emancipation of the slaves. He also supported self-improvement efforts of northern free blacks as a means of combating pervasive racial prejudice. He distributed thousands of acres of unimproved land in upstate New York to poor black families to help them become economically independent. Smith initially believed that the abolitionist mission was exclusively one of moral suasion: to "publish the truth about slavery."

Smith's great fortune allowed him to become one of the leading philanthropists of the early nineteenth century. Although he was antisectarian in his personal religious beliefs, Smith gave generously to the American Bible Society, the American Tract Society, and the American Sunday School Union….Smith became a leader and major financial sponsor of state and national organizations promoting temperance, prison reform, international peace, and land reform. He also supported his wife's and his daughter Elizabeth Smith Miller's active participation in the women's rights movement.

The cause that captured the greatest portion of Smith's attention was the campaign to end slavery. At first Smith supported efforts to colonize slaves in Africa, but in 1835 he joined the more militant abolitionist movement that demanded immediate emancipation of the slaves. He also supported self-improvement efforts of northern free blacks as a means of combating pervasive racial prejudice. He distributed thousands of acres of unimproved land in upstate New York to poor black families to help them become economically independent. Smith initially believed that the abolitionist mission was exclusively one of moral suasion: to "publish the truth about slavery."

John R. McKivigan, "Smith, Gerrit," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00627.html.