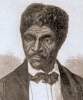

Dred Scott (American National Biography)

Unanticipated developments converted an open-and-shut freedom suit into a cause célèbre. In the trial on 30 June 1847, the court rejected one piece of vital evidence on a legal technicality--that it was hearsay evidence and therefore not admissible--and the slave's freedom had to await a second trial when that evidence could be properly introduced. It took almost three years, until 12 January 1850, before that trial took place, a delay caused by events over which none of the litigants had any control. With the earlier legal technicality corrected, the court unhesitatingly declared Dred Scott to be free.

Dred Scott (Bailey, 1998)

Dred Scott (Roark, 2002)

Eleven years after the Scotts first sued for freedom, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case. The justices could have simply settled the immediate issue of Scott’s status as a free man or slave, but they saw the case as an opportunity to settle once and for all the vexing question of slavery in the territories. On the morning of March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney read the majority decision of the Court. Taney hated Republicans and detested racial equality, and the Court’s decision reflected those prejudices. First, the Court ruled that Dred Scott could not legally claim violation of his constitutional rights because he was not a citizen of the United States. At the time of the Constitution, Taney said, blacks “had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order…so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Second, the laws of Dred Scott’s home state, Missouri, determined his status, and thus his travels in free areas did not make him free. Third, Congress’s power to make “all needful rules and regulations” for the territories did not include the right to prohibit slavery. The Court then explicitly declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, even though it had already been voided by the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

Republicans exploded in outrage. Taney’s extreme proslavery decision ranged far beyond a determination of Dred Scott’s freedom. By declaring unconstitutional the Republican program of federal exclusion of slavery in the territories, the Court had cut the ground from beneath the party.

Dred Scott (New York Times)

Dred Scott.

It is not well to let the great pass away without note and worthy

honor. DRED SCOTT is dead. Yesterday, from St. Louis, that illustrious

personage carried his case to the Supreme Court above, not doubting, we

may believe, that the adverse decision he encountered here will there

meet with reversal, and that he will be at once admitted to a better

freedom and more equal citizenship. It is only now and then we are

called to regret the loss of the truly eminent. Once or twice, perhaps,

in a generation. DRED is of these. His name will live when those of

CLAY, and CALHOUN, and BENTON will be feebly remembered or wholly

forgotten. Posterity will make inquiry about the subject of that great

leading case, decisive of human right, upon which the fate of the Union

was in his day presumed to depend, and will gather up what particulars

lie scattered up and down contemporary chronicles regarding him. So, by

all means, let the noted negro have his obituary and monument with the

rest.

DRED SCOTT died at a very advanced age. Longer ago than anybody can

remember, he was born, down in Virginia, on the property of the BLOW

family, which, from the name, we may judge to be extensively connected

with the first families. Captain PETER BLOW, while yet our hero was of

tender years, moved away from the home of his race to Missouri,

carrying DRED with him; and there, as was to be anticipated even for

the BLOWS, succumbed to the common fate. After other changes, and after

accepting the claims of several reputable gentlemen in succession to

the ownership of his soul, the Negro, in 1834, came into the hands of

Dr. EMERSON, a surgeon in the Army, who carried him along to Rock

Island, in Illinois, and subsequently to Fort Snelling, in the

Northwest Territory of that day. At the latter point, in 1836, he

married HARRIET, another chattel of the migratory surgeon, by whom he

had the two children who figured in the suit, ELIZA and LIZZIE, and who

still live. Dr. EMERSON, in 1838, gave over his roaming, settling down

quietly in Missouri, where some dozen years ago he died, leaving the

slaves in trust to Mr. JOHN F. A. SANDFORD, the executor of his will,

and the defendant in the famous suit. It is ten years ago since DRED

brought suit for his freedom, and that of his wife and family, in the

Circuit Court of St. Louis, asserting it on the ground of their owner

having voluntarily taken them, in the first instance, to soil declared

free by the ordinance of 1787; in the second place, to soil acquired by

treaty with Louisiana, north of 36° 30’, and therefore free by the

terms of the Missouri Compromise. His claim was held valid by the local

Court; but, upon appeal, it was denied by the Supreme Court of the

State, which sent the case back to the lower tribunal. It passed thence

into the Circuit and Supreme Courts of the United States, where, at the

December Term of 1856, it was finally decided against DRED and his

pretensions. The majority of the Court were of opinion that

“A negro held in Slavery in one State, under the laws thereof, and

taken by his master, for a temporary residence, into a State where

Slavery is prohibited by law, and thence into a Territory acquired by

treaty, where Slavery is prohibited by act of Congress, and afterwards

returning with his master into the same Slave State, and resuming his

residence there, is not such a citizen of that State as may sue there

in the Circuit Court of the United States, if by the law of that State

a negro under such circumstances is a Slave.”

Of course this decision, with the general results of which we have now

nothing to do, extinguished the hopes of the hapless DRED. The freedom

he sighed for was not, however, so remote as he supposed. Shortly after

the judgment his owner determined, indeed had long previously

determined, but then proceeded, to consummate the emancipation of the

veteran negro and his family. The owner was the Hon. CALVIN C. CHAFFEE,

of Massachusetts. But, as under the laws of Missouri the act of

emancipation can only be performed by a citizen of that State, the four

items of personal property were made over to Mr. TAYLOR BLOW, a son of

Capt. PETER above referred to, who, on the 26th of May, 1857, gave

liberty to the happy captives. The transaction was probably as

gratifying as it was becoming to Mr. BLOW, who a half century before

had been a play-mate of the colored hero. We have been informed that

charitable hands have smoothed the later path of DRED and his HARRIET,

so that a freedom so tardily come by, has not been attended by its

usual awkwardness, abuse and suffering.

Of a truth, few men who have achieved greatness have won it so

effectually as this black champion. There is little it may be of merit

in his personal service. Others doubtless, for uses of their own, have

prompted and paid for the fight. But he belongs to a class whose names

are accidentally but ineffacebly associated with critical or memorable

facts in history; and who are therefore surer of immortality than the

authors themselves of the events. The “Clay Compromise,” the “Wilmot

Proviso,” the “Dred Scott Decision,” the “English Bill,” of

contemporary annals, are to be classed with the “Lex Julia,” the

“Methuen Treaty,” the “Code Napoleon,” of the past; facts and results,

to which chance rather than merit has attached names, which they shall

perpetuate indefinitely. It shall always be remembered that in the

person of the old negro who died yesterday the highest tribunal of

America decided that an African was not a man, and could not therefore

be a citizen of the United States.

Dred Scott (Liberator)

DRED SCOTT GONE TO FINAL JUDGMENT.

The old negro whose name has attained such historical prominence in this country, in connection with the Missouri compromise, the Supreme Court, and the general question of African slavery, is now done with the things of time; and, though he had no status before the Supreme Court of the United States, there is no reason to suppose that his color or condition excluded him from the presence of the great Judge of the universe. In ages yet to come, when the names of the minor actors in the politics of the day will have been forgotten, Dred Scott and the decision which bears his name will be familiar words in the mouth of the ranting demagogue in rostrum and pulpit, and of the student of political history. The telegraph informs us that Dred died on Friday, the 17th inst., in the city of St. Louis; and, although the Supreme Court of the United States overruled his claims to freedom, he died a free man, and with the consciousness that his wife Harriett and his two young daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, were also loosed from their bonds.

Although Dred’s name has made such a stir in the world, his life was by no means an eventful one. He was born on the plantation of the Blow family, in Virginia, and up to about his tenth year he enjoyed his share of the fun, frolic and sports that usually fall to the lot of such fortunate ebon youngsters. He was subsequently carried by his master to St. Louis, and it was during his abode in that city, we believe, that he changed masters, Blow having sold him to Dr. Emerson, then a surgeon in the United States army. In the course of his new master’s military career, Dred found himself, from 1834 to 1836, located at the military post at Rock Island, in Illinois, and subsequently at the since famous Fort Snelling, in Minnesota. Dr. Emerson died, and his widow became, and now is, the wife of the Hon. Calvin C. Chaffee, member of Congress from the State of Massachusetts.

For some ten years before the death of Dr. Emerson – which event occurred about twelve years since – he had resided in St. Louis, Dred Scott being one of the household. But while at Fort Snelling, Dred had taken unto himself as wife the girl Harriet, then also a slave of Major Taliaferro, of the United States army. This was his second wife. His first died childless. Harriet bore him four children, two only of whom are living. Their names are Eliza and Lizzie, and their ages are respectively about ten and fifteen. After the death of Doctor Emerson, Dred Scott became the body servant of Capt. Brainbridge, and was at Corpus Christi on the breaking out of the Mexican war. On his return to St. Louis, he made application to his late mistress on the subject of purchasing the freedom of himself and family. She, however, was adverse to the proposition, and refused to entertain it. Then it was that the ‘Dred Scott case’ commenced. Dred was informed that having been voluntarily taken by his master into free territory (Illinois and Minnesota), he by that act became free. He, therefore, about ten years ago, brought a suit for his freedom against the executor of Dr. Emerson’s will – Mr. John F. A. Sanford – and the Circuit Court of St. Louis decided in his favor. That decision, however, was overruled by the Supreme Court of the State of Missouri; and thence it came before the Supreme Court of the United States, which refused to entertain it on the ground that the descendants of Africans who had been sold here as slaves, were not, under the constitution, citizens of the United States, and therefore not entitled to sue in the Supreme Court. This decision was made the text for vituperative assaults from the press, pulpit and rostrum against the Supreme Court of the United States; and as well for the principles it settles as for the dicta it lays down, will continue to be, as it has been, the fruitful theme of politicians of both sections for perhaps centuries to come.

But, although the decision was not such as Dred Scott had been led to believe or hope, and although under it he and his family were in the condition of chattel property, still he, in reality, lost nothing by it. His real owner had been Mr. Chaffee, although the suit was brought against Sanford, the executor of Emerson’s will. A representative of the commonwealth of Massachusetts could not, with any sort of grace, be the proprietor of human chattels. But, as he was a non-resident of the State, he could not, under the laws of Missouri, emancipate his slaves. These laws, however, are easily circumvented, where the disposition to do so exists, as it did in this case. The Scotts – parents and children – were conveyed back to the representative of their original propriety, Mr. Taylor Blow, of St Louis – ‘one of them boys he was raised with’ – as Dred used to express it, and this Mr. Blow formally entered up their emancipation in the proper court.

Dred was probably not over fifty years of age at his death, although the general impression was that he was quite an old darkey. His widow is considerably his junior. She follows the business of a laundress in St. Louis, and Dred used to aid her in the business by carrying the clothes back and forward. The girls disappeared as soon as they learned the effect of the Dred Scott decision, but they subsequently returned to the parental roof. – N. Y. Herald.