| Iconic image | Title | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Election of 1852 | Democrat Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire secured victory in the presidential election of 1852 against his Whig opponent General Winfield Scott. The election marked the last national campaign for the Whigs and signaled the beginning of a realignment in American partisan politics. (By Matthew Pinsker) |

|

| Election of 1856 | The 1856 presidential contest was a three-way affair involving Democrat James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, Republican John Fremont, the famed western explorer, and American or Know Nothing candidate Millard Fillmore, the former president. The exciting contest marked a new, more openly sectional era in American politics but resulted in victory for Buchanan, who aspired to forge a national consensus for compromise on the difficult issue of slavery. (By Matthew Pinsker) |

|

| Election of 1860 | The election of 1860 may have been the most significant in American history. It was certainly the only contest so far where the losing party refused to accept the results. Abraham Lincoln became the first Republican elected to the White House, securing an easy electoral majority but with just less than 40 percent of the popular vote. Within weeks, states from the Deep South, led by South Carolina, began to secede from the union. (By Matthew Pinsker) |

|

| Election of 1864 | ||

| Election of 1876 | ||

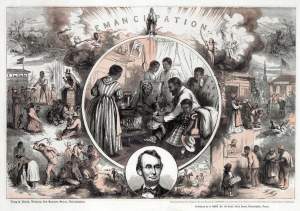

| Emancipation | ||

| Filibustering | Filibustering was a term that referred to unofficial and irregular American efforts in the mid-nineteenth century to expand the empire of slavery into Central and Latin America. Figures such as William Walker, the "grey-eyed man of destiny," became celebrated in the South as heroes and vilified in the North as pirates for their various military exploits and adventures during the 1850s. (By Matthew Pinsker) |

|

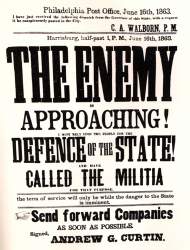

| Fort Sumter | The bombardment of Fort Sumter which began on Friday, April 12, 1861 marked the beginning of the Civil War. Months of maneuvering between federal authorities and the newly formed Confederate States of America over control of federal forts in southern territory culminated with the surrender of the Charleston, South Carolina fort on April 14. Days later, President Lincoln declared that an insurrection existed, officially calling out the militia, and launching the nation into a full-scale military conflict. (By Matthew Pinsker) |

|

| Fortieth Congress of the United States | ||

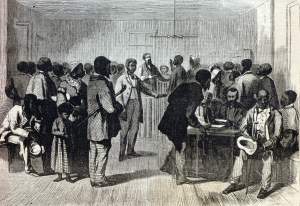

| Freedmen's Bureau - Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands | ||

| Fugitive Slave Law | The 1850 federal fugitive slave law amended an earlier statute from 1793 that had provided for the return of runaway slaves who crossed state lines. The new, tougher measure was an essential component of the so-called Compromise of 1850 because the measure was designed to address longstanding southern complaints about the Underground Railroad. Resistance to the new law, however, soon proved widespread and the measure only further inflamed sectional antagonism. (By Matthew Pinsker) |

|

| Gettysburg Campaign | ||

| Gilded Age Politics | ||

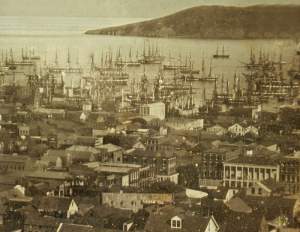

| Gold Rush | Gold discovered in California at the beginning of 1848 helped change the fate of the union by encouraging an influx of white settlers in the final months of the 1840s and putting pressure on the federal government to admit the former Mexican province as a new state. The intense sectional debate over slavery made the decision over California statehood an explosive one ultimately leading to the national Compromise of 1850. James W. Marshall was the man who made the initial gold discovery on January 24, 1848 at John Sutter's Mill in northern California (near present-day Sacaramento). Marshall was a native of New Jersey and a veteran of the Mexican War who worked for Sutter. The discover soon became public and the rapid expansion of gold mining eventually drew more than 500,000 prospecters and opportunists to California. The "gold rush" became a cultural symbol of a new age. Yet major gold mining in California died out quickly and major gold operations ceased by the end of the Civil War. James Marshall, the original prospecter, received some fame for his discovery but made little money from his find and died in poverty in 1885. (By Matthew Pinsker) |

|

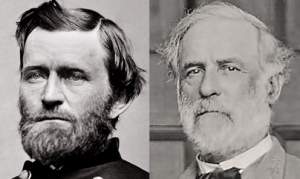

| Grant vs. Lee | ||

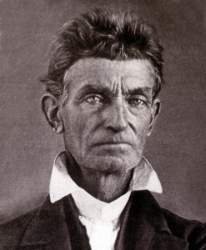

| Harpers Ferry Raid | John Brown's raid at Harpers Ferry in October 1859 has long been regarded as one of the pivotal events in the coming of the Civil War, but both the nature of the attack and its impact on American society were more complicated than most people or some textbooks acknowledge. On Sunday evening, October 16, 1859, John Brown and eighteen other men walked from a farmhouse in western Maryland a few miles into the town of Harpers Ferry, Virginia in order to seize weapons from the largely unguarded federal arsenal. Three others from the group stayed behind and guarded their headquarters. What the raiders planned to do with the federal rifles, and the hundreds of menacing pikes that Brown had ordered in advance of the attack, remains a subject of some dispute. John Brown had been an agent in the Underground Railroad helping slaves escape to freedom for decades before he came to Harpers Ferry. He hated slavery and had spent much of his adult life fighting against the institution with words and deeds, sometimes quite violent deeds. For example, Brown and some of his sons had participated in the small-scale wars over slavery that had ripped apart the Kansas territory and had mudered at least five pro-slavery settlers in a notorious incident in 1856. They had also helped nearly a dozen slaves, including a pregnant woman, escape from Missouri in December 1858, escorting them safely to Detroit by March 1859 in what might have been a dress rehearsal for another "slave-stealing" raid into Virginia later that year. But during this time, Brown and his Provisional Army, as they called themselves, also seemed to be hatching wild plans for a revolution, what a Virginia court would later declare as a treasonous attempt to launch a slave insurrection. Partly because of these sweeping and grandiose schemes, and partly because the tactical planning for the actual raid at Harpers Ferry later seemed so inadequate to those purposes, Brown gained a reputation as crazed. Yet he was also a charismatic leader whose courage impressed everyone from former slaves to New England intellectuals (some of whom funded the raid) and even to some southern journalists and politicians who later encountered him in prison. The raid itself did fail. Despite initial success on Sunday evening in capturing rifles at the arsenal and in rounding up prominent local hostages, Brown's forces soon got separated and surrounded without any hope of reinforcements. Several of Brown's men were killed in the attack which lasted nearly 36 hours. Others, including Brown himself, who was wounded in the final assault at the arsenal's engine house, were captured. But some escaped. And Brown's behavior during his subsequent trial at Charlestown, Virginia (later West Virginia) captivated public attention, thrilling anti-slavery audiences in the North and horrifying many pro-slavery southerners. The Commonwealth of Virginia executed Brown on December 2, 1859, but the man and his failed raid remained a subject of intense public debate throughout the 1860 presidential campaign. Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln even felt compelled to denounce Brown in order to separate himself from the violence. Yet within a couple of years later, Union soldiers would sing "John Brown's Body" as they marched into battle. The memory of John Brown's actions remains controversial and widely debated. (By Matthew Pinsker) |

|

| Invasion of Maryland | ||

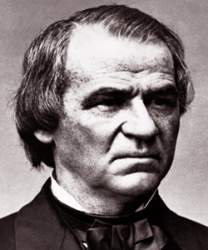

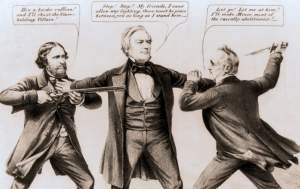

| Johnson's Impeachment | ||

| Kansas-Nebraska Act | ||

| Know Nothings |