Frederick Douglass, Abolitionist Activities (American National Biography)

Frederick Douglass, Escape from Slavery (American National Biography)

After an unsuccessful attempt to buy his freedom, Frederick escaped from slavery in September 1838. Dressed as a sailor and carrying the free papers of a black seaman he had met on the streets of Baltimore, he traveled by train and steamboat to New York. There he married Anna Murray, a free black domestic servant from Baltimore who had encouraged his escape...he adopted the surname Douglass to disguise his background and confuse slave catchers.

Frederick Douglass, Slave Narrative (American National Biography)

Douglass bristled under such paternalistic tutelage. An answer was to publish an autobiography providing full details of his life that he had withheld. Although some friends argued against that course, fearing for his safety, Douglass sat down in the winter of 1844-1845 and wrote the story of his life. The result was the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself (1845). The brief autobiography, which ran only to 144 pages, put his platform tale into print and reached a broad American and European audience. It sold more than 30,000 copies in the United States and Britain within five years and was translated into French, German, and Dutch. Along with his public lectures, "the Narrative made Frederick Douglass the most famous black person in the world."

Frederick Douglass (Dictionary of American Biography)

Frederick Douglass (New York Times)

That everybody speaks of Frederick Douglass as “Fred” Douglass is in itself an illustration of the unique position he occupied in our political life. It is noteworthy that he himself always resented the nickname, and his resentment was a punctilio that showed that he knew what it meant. It was, in truth, a sign of the patronage of the white race for a man of color who had done remarkably well, “considering.” It was a mark of the prejudice against which it is equally futile to argue and to pass statutes. Senator Sumner thought that the civil rights law would do something to dispel what he used to call the “accursed spirit of caste,” but it did nothing, for the reason that this spirit is entirely beyond the province of legislation. It is quite impossible to compel a man to associate with people with whom, for any good or bad reason, he does not choose to associate, and the very great majority of white men in this country will not associate with men of color, on equal terms, even if the men of color be their fellow-cadets at West Point or their fellow-members of the House of Representatives or the Senate. If Mr. Douglass had been a white man nobody would have thought of describing by a diminutive a personage of such conscious dignity of bearing and of so little disposition to familiarity. His resentment was quite natural, for the nickname denoted the prejudice which he had to meet and which made him, as we say, a figure quite unique.

There have been men of color who attained higher offices than Fred Douglass. At least one has been a Senator of the United States, and at a time when the Senate was a much more reputable body than it is now. But for quite half a century he was recognized as the representative man of his race, the man who would be named first by whoever might have been called upon to designate the most distinguished men of color in the country. Perhaps he owed this distinction in part to his very impressive personality, which grew more impressive with advancing years. Unlike many men of mixed blood who have become conspicuous, he bore the unmistakable evidence of African descent in his appearance. He might indeed have been taken for a full-blooded African, of a type which is very seldom reached. But the qualities by which he attained celebrity were such as no full-blooded African in our history has displayed in the same degree. He was ambitious, industrious, and provident, and by the manifestation of these qualities he drew apart from his race and was not really a representative “African American.” It was not surprising to learn that he was not altogether persona grata when he was appointed Minister to Haiti, although his appointment may have seemed to those who made it a stroke of policy. It is well known that the full-blooded blacks in Haiti are opposed to men of mixed race, of whom Douglass was one, and the Haitian rulers were disposed to resent the appointment that was expected to please them. In fact, a man like Douglass is in a painful and “impossible” position. Every step that he makes in advance of the inferior race from which he derives part of his ancestry is credited by the whites to his white blood, and indeed there is no conspicuous instance of such steps being taken by a full-blooded African. By taking them he separates himself from his “own people,” as both whites and blacks consider the blacks to be, and he is at home nowhere. It is significant that the blacks should generally have regarded his espousal of a white woman for his second wife as an act of “treason,” though indeed it was the natural consequence of his own development. He was a man of integrity, of intelligence, of dignity, of benevolence. But these qualities, instead of solving the “race question,” in his case simply served to propound that question more sharply. They made it appear that a man who differed from his race for the better was isolated and made unhappy by the difference, without being enabled to effect anything for the benefit of his race.

Frederick Douglass, Obituary (New York Times)

WASHINGTON, Feb, 20, - Frederick Douglass dropped dead in the hallway of his residence on Anacostia Heights this evening at 7 o’clock. He had been in the highest spirits, and apparently in the best of health, despite his seventy-eight years, when death overtook him.

This morning he was driven to Washington, accompanied by his wife. She left him at the Congressional Library, and he continued to Metzerott Hall, where he attended the sessions of the Women’s Council in the forenoon and the afternoon, returning to Cedar Hill, his residence, between 5 and 6 o’clock. After dining, he had a chat in the hallway with his wife about the doings of the council. He grew very enthusiastic in his explanation of one of the events of the day, when he fell upon his knees, with hands clasped.

Mrs. Douglass, thinking this was part of his description, was not alarmed, but as she looked he sank lower and lower, and finally lay stretched upon the floor, breathing his last. Realizing that he was ill, she raised his head, and then understood that he was dying. She was alone in the house, and rushed to the front door with cries for help. Some men who were near by [sic] quickly responded, and attempted to resaore [sic] the dying man. One of them called Dr. J. Stewart Harrison, and while he was injecting a restorative into the patient’s arm, Mr. Douglass passed away, seemingly without pain.

Mr. Douglass had lived for some time at Cedar Hill with his wife and one servant. He had two sons and a daughter, the children of his first wife, living here. They are Louis H. and Charles Douglass and Mrs. Sprague.

Mr. Douglass was to deliver a lecture tonight at Hillsdale African Church, near his home, and was waiting for a carriage when talking to his wife. The carriage arrived just as he died.

Mrs. Douglass said tonight that her husband had apparently been in the best of health lately, and had shown unusual vigor for one of his years. No arrangements, she said, would be made for his funeral until his children could be consulted.

It is a singular fact, in connection with the death of Mr. Douglass, that the very last hours of his life were given in attention to one of the principles to which he has devoted his energies since his escape from slavery. This morning he drove into Washington from his residence, about a mile out from Anacostia, a suburb just across the eastern branch of the Potomac, and at 10 o’clock appeared at the Metzerott Hall, where the Women’s National Council is holding its triennial. Mr. Douglass was a regularly-enrolled member of the National Women’s Suffrage Association, and always attended its conventions. It was probably with a view to consistency in this respect that he appeared at Metzerott Hall….

Frederick Douglass has been often spoken of as the foremost man of the African race in America. Though born and reared in slavery, he managed, through his own perseverance and energy, to win for himself a place that not only made him beloved by all members of his own race in America, but also won for himself the esteem and reverence of all fair-minded persons, both in this country and in Europe.

Mr. Douglass has been for many years a prominent figure in public life. He was of inestimable service to the members of his own race, and rendered distinguished service to his country from time to time in various important offices that he held under the government.

He became well known, early in his career, as an orator upon subjects relating to slavery. He won renown by his oratorical powers both in the northern part of the United States and in England. He had become known before the civil war also as a journalist. So highly were his opinions valued that he was often consulted by President Lincoln, after the civil war began, upon questions relating to the colored race. He held important offices almost constantly from 1871-1891.

Mr. Douglass, perhaps more than any other man of his race, was instrumental in advancing the work of banishing the color line.

Mr. Douglass’s life from first to last was filled with incidents that gave to it a keen flavor of romance.

The exact date of his birth is unkown. It was about the year 1817. His mother was a negro slave and his father was a white man. Mr. Douglass’s birthplace was on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, in the Tuckahoe district. He was reared as a slave on the plantation of Col. Edward Lloyd. He was sent, when ten years old, to one of Col. Lloyd’s relatives in Baltimore. Here he was employed in a shipyard.

Douglass, according to his own story, suffered deeply while under the bonds of slavery. His superior intelligence made him conscious of his wrongs and rendered him keenly sensitive to his condition. The manner in which he acquired the rudiments of his education has become a familiar story. He learned his letters, it is said, from the carpenters’ marks on planks and timbers in the shipyard. He used to listen while his mistress read the Bible, and at length asked her to teach him to read it for himself. All the while he was in the shipyard he continued to pick up secretly all the information he could.

It was while here, too, that he heard of the abolitionists, and began to formulate plans for escaping to the North. He made his escape from slavery Sept. 3, 1838, and came to New-York. Thence he went to New-Bedford, where he married. He supported himself for two or three years by day labor on the wharves and in the workshops.

He made a speech in 1841 at an antislavery convention, held at Nantucket, that made a favorable impression, and he became the agent of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. He then traveled four years through New-England, lecturing against slavery.

He went to England in 1845, where his lectures in behalf of the slave won a great deal of attention. He also visited Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. Mr. Douglass’s friends in England feared that he might be captured and forced back into slavery, and so they raised £150, by means of which he was afterwards formally manumitted.

Mr. Douglass often met with many unpleasant experiences while traveling about, owing to the prejudice that was felt against his race. On one occasion, when the passengers on a boat would not allow him to enter the cabin, his friend, Wendell Phillips, refused to leave him, and the two men spent the night together on deck.

William Lloyd Garrison had also become interested in young Douglass, and before Douglass went to England had done all he could to assist him in gaining an education. Throughout the anti-slavery agitation, Mr. Douglass’s efforts in behalf of the slaves was [sic] unflagging.

On returning from England Mr. Douglass founded Frederick Douglass’s Paper, a weekly journal, at Rochester, N.Y. The title was changed to The North Star. He continued its publication for several years.

Mr. Douglass and John Brown were friends, and had the same objects in view. Douglass, however, did not approve of Brown’s plan for attacking Harper’s Ferry, and the men parted some two weeks before the attack was made. Douglass was in Philadelphia the night the Harper’s Ferry episode occurred. It became plain to him immediately afterward that he could scarcely hope to escape being implicated in the trouble, and at the earnest solicitation of his friends he made his escape to Canada. United States Marshals appeared in Rochester to apprehend him a few hours after his flight. He discovered, many years later, that a requisition for his arrest had been made by the Governor of Virginia. He went to Quebec, and thence to England, where he remained six or eight months. He afterward returned to Rochester, and again took charge of his paper.

Mr. Douglass urged upon President Lincoln, when the civil war began, the employment of colored troops and the proclamation of emancipation. Permission for organizing such troops was granted in 1863, and Mr. Douglass became active in enlisting men to fill the colored regiments, notably the Fifty-fourth and the Fifty-fifth Massachusetts.

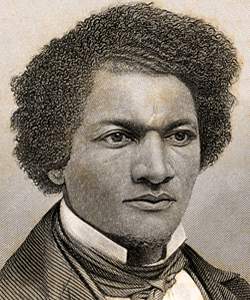

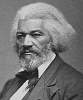

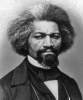

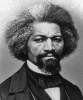

Mr. Douglass returned to the lecture field after slavery had been abolished. He attracted great crowds wherever he went. His appearance on the platform was imposing. His height was over 6 feet and his weight was fully 200 pounds. His complexion was swarthy rather than black. His head was covered with a great shock of white hair. A large head, low forehead, high cheekbones, and large mouth, with gleaming white teeth, were some of the noticeable characteristics of his appearance. As a speaker he was characterized by his earnestness. He made but few gestures and used simple language.

He became the editor in 1870 of The New National Era, in Washington, which was afterward published by his sons, Lewis and Frederick.

He received the appointment in 1871 as Assistant Secretary to the commission to San Domingo, and on his return from that mission President Grant appointed him one of the Territorial Council of the District of Columbia. He was elected Presidential Elector at Large for the State of New-York in 1872, and was appointed to carry the electoral vote of the State of Washington.

Mr. Douglass was appointed United States Marshal for the District of Columbia in 1876, and retained that office till 1881, when he became Recorder of Deeds in the District of Columbia. President Cleveland removed him from that office in 1886. In the Autumn of that year he made a third visit to England.

President Harrison made Mr. Douglass Minister to Haiti in 1889. He resigned this office in August, 1891. Mr. Douglass’s administration in Haiti was not entirely satisfactory, and for some time previous to his resignation unfavorable reports of the affairs of his office reached Washington. Mr. Douglass went to Haiti just after the revolution that put Hippolyte in power, and that country was still in an unsettled condition. The Haitians did not take kindly to Mr. Douglass, because of his race, and failed to give him the respect to which his office should have entitled him. It was recognized when President Harrison appointed him that it was an experiment, the outcome of which was very uncertain. Some one in commenting on Mr. Douglass’s actions in Haiti said that he seemed to consider himself rather the representative of the United States Government. Admiral Gherardi, who visited Haiti while Mr. Douglass was there, brought back to Washington very unfavorable reports of the condition of affairs there. There was a great deal of comment in one way and another, and Mr. Douglass thought best to resign. He said, however, thet the reports about his having been snubbed by Haitian officials had been grossly exaggerated.

Mr. Douglass wrote several books that have met with considerable sale. Among them are “Narrative of My Experience in Slavery,” 1844; “My Bondage and My Freedom,” 1855; “Life and Times of Frederick Douglass,” 1881.

Of recent years he has always been prominent in all movements having in view the social and political advancement of women, and no later than yesterday afternoon was a welcome attendant at the session of the Women’s National Council, where he was honored with a seat on the platform.

Fred Douglass was married twice, his second wife being Miss Pitts, a white woman from New-York State, who was a clerk in the Recorder’s office while he held that position. For a time this lost him some caste among the people of his own race, but his personal standing and overpowering intellectuality quickly dissipated the sentiment that some sought to disseminate to his discredit. He was one of the most distinguished-looking men that appeared on the thoroughfares of the capital. He was kindly disposed to all, courteous, and of gentle bearing, and by all alike, white and black, or of whatever creed, religion, or race, the news of his death will meet only with genuine regret.

There is no end of stories about Mr. Douglass. One of his most marked characteristics was his intense dislike to being addressed or spoken of us Fred Douglass. It is told of him that one day, when in the East Room of the White House, on overhearing a woman say, “There’s Fred Douglass,” he turned to her, made a courtly bow, and said, “Frederick Douglass, if you please.”

In addressing a colored school, March 24, 1893, at Easton, Md., near his birthplace, Mr. Douglass said:

“I once knew a little colored boy whose mother and father died when he was but six years old. He was a slave and had no one to care for him. He slept on a dirt floor in a hovel, and in cold weather would crawl into a mealbag head foremost and leave his feet in the ashes to keep them warm. Often he would roast an ear of corn and eat it to satisfy his hunger, and many times has he crawled under the barn or stables and secured eggs, which he would roast in the fire and eat.

“That boy did not wear pantaloons, as you do now, but a tow linen shirt. Schools were unknown to him, and he learned to spell from an old Webster’s spelling book and to read and write from posters on cellar and barn doors, while boys and men would help him. E would then preach and speak, and soon became well known. He became Presidential Elector, United States Marshal, United States Recorder, United States diplomat, and accumulated some wealth. He wore broadcloth and didn’t have to divide crumbs with the dogs under the table. That boy was Frederick Douglass.

“What was possible for me is possible for you. Don’t think because you are colored you can’t accomplish anything. Strive earnestly to add to your knowledge. So long as you remain in ignorance so long will you fail to command the respect of your fellow-men.”