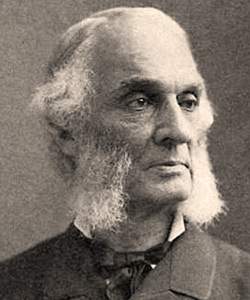

Robert Purvis (American National Biography)

Scholarship

[Robert Purvis] was born in Charleston, South Carolina, the son of William Purvis, a naturalized British cotton broker, and Harriet Judah, the free mulatto daughter of a German Jewish flour merchant and an emancipated slave of Moorish extraction…An intimate of James Forten, the wealthy black sailmaker, Purvis threw himself into anticolonization activities, denouncing the design to deport free blacks to colonies outside the United States. He married Forten's daughter, Harriet, in 1831; they had eight children. After Harriet's death in 1875, he married Tacy Townsend, a white Quaker. When Lundy's associate, William Lloyd Garrison, looked to publish The Liberator (1831) and his hostile Thoughts on African Colonization (1832), Purvis and Forten aided him by gathering subscriptions and raising funds. Both were charter members of the American Anti-Slavery Society formed in Philadelphia in 1833. Following the first annual meeting of the society, Purvis, sailed in 1834 to Britain, having obtained a U.S. passport through the intervention of President Andrew Jackson, where for three months he promoted the American antislavery cause and visited relatives. His return voyage provided him with a tale he delighted to tell for the remainder of his life: he had been showered with social courtesies by fellow passengers, notably the racial purist Arthur Peronneau Hayne of South Carolina, all of them miscued by his light complexion, until he disclosed, shortly before landing, that he belonged "to the degraded tribe of Africans."

Joseph A. Boromé, "Purvis, Robert," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00559.html.

Robert Purvis, Civil War (American National Biography)

Scholarship

Purvis welcomed armed conflict to end slavery, but after the Civil War began, he criticized the race-related policies of President Abraham Lincoln, particularly his proposal to deport and colonize freed slaves. He grew to trust the Lincoln administration, however, and took heart from Attorney General Edward Bates's declaration that he believed blacks were citizens, the Dred Scott decision notwithstanding. After the official release of the Emancipation Proclamation, Purvis admitted freely that he was "proud to be an American citizen." When the government began recruiting black troops in 1863, he urged black volunteers to enlist at Camp William Penn near Philadelphia. Joining with others to organize the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League in 1864, he rejoiced at the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments, although he remained a disappointed yet steadfast proponent of woman suffrage.

Joseph A. Boromé, "Purvis, Robert," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00559.html.

Robert Purvis, Reconstruction (American National Biography)

Scholarship

Greatly respected in the postwar era, Purvis refused an 1867 bid to head the Freedmen's Bureau but served as a commissioner in Washington, D.C., of the Republican-sponsored Freedmen's Savings Bank (1874-1880). After returning to Philadelphia, he dedicated himself, as an elder statesman of abolitionism, to the defeat of slavery's "twin relic of barbarism, prejudice against color." He supported municipal reform and independent political action to battle race discrimination in city employment, to ameliorate the economic plight of black workers, and to shore up civil rights. In 1881 he backed for mayor reform Democrat Samuel G. King, who after election appointed four black policemen. In 1884, ignoring mounting Republican displeasure because he did not adhere to the party that had freed the slaves, Purvis flirted with the Greenback party. Dissatisfied with the 1887 state civil rights law, he lobbied for more inclusive legislation.

Joseph A. Boromé, "Purvis, Robert," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00559.html.