Anthony Burns (American National Biography)

Scholarship

The Burns affair was the most important and publicized fugitive slave case in the history of American slavery because of its unique set of circumstances. It coincided with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and with the Sherman M. Booth fugitive slave rescue case earlier that year, all of which contributed to national political realignment over the slavery issue. In Massachusetts, antislavery parties succeeded Whiggery. Eight states now enacted new personal liberty laws to counter the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. An 1855 Massachusetts statute protected alleged fugitives with due process of law while punishing state officials and militiamen involved in recaption. Two Know Nothing legislatures resolved to remove Loring from his state probate office under this statute, but the governor refused to comply. In 1858 a Republican governor and legislature did remove him, occasioning a dramatic debate in the house between John Andrew, defender of the courthouse rioters who argued for removal, and Caleb Cushing, the attorney general who had ensured the fugitive's return and prosecuted the rioters. After Burns's rendition, no owner chanced recovery in the city.

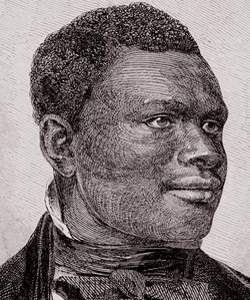

Throughout his ordeal Anthony Burns demonstrated his intelligence and resourcefulness, courage and humor, honesty and integrity. As the victimized protagonist of the affair, he became "the fugitive." He originally had discouraged the legal defense that Bostonians urged on his behalf, telling his lawyer that "I shall fare worse if I resist," for his master was "a malicious man if he was crossed." And so he was returned, punished, sold, and celebrated as the "Boston Lion."

Throughout his ordeal Anthony Burns demonstrated his intelligence and resourcefulness, courage and humor, honesty and integrity. As the victimized protagonist of the affair, he became "the fugitive." He originally had discouraged the legal defense that Bostonians urged on his behalf, telling his lawyer that "I shall fare worse if I resist," for his master was "a malicious man if he was crossed." And so he was returned, punished, sold, and celebrated as the "Boston Lion."

David R. Maggines, "Burns, Anthony," American National Biography Online,, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/20/20-00129.html.

Anthony Burns (Von Frank, 1998)

Scholarship

Anthony Burns was not a stereotypical slave: he never worked the tobacco fields, and indeed never did any kind of agricultural work. Apart from the fact that his wages seemed always to end up in his master's pocket, the most distinctive feature of hs labor history was that it had annually a new chapter. Once he worked in a lumber mill and once in a flour mill, but most often he was a clerk or stock boy in a store in some town or city in eastern Virginia. His last slave job before his escape was one he found for himself, as a stevedore in Richmond. Although he was certainly and continuously exploited, there is no suggestion that he was worked unusually hard. If he was ever beaten, no serious allegation to that effect survives.

Albert J. Von Frank, The Trials of Anthony Burns: Freedom and Slavery in Emerson's Boston (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1998), xiv-xv.

Anthony Burns (A Short History of the American Negro)

Reference

It was not long before public sentiment began to make itself felt, and the first demonstration took place in Boston. Anthony Burns was a slave who escaped from Virginia and made his way to Boston, where he was at work in the winter of 1853-4. He was discovered by a United States marshal who presented a writ for his arrest just at the time of the repeal of the Missouri Compromise in May, 1854. Public feeling became greatly aroused. Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker delivered strong addresses at a meeting in Faneuil Hall while an unsuccessful attempt to rescue Burns from the Court House was made under the leadership of Thomas W. Higginson, who, with others of the attacking party, was wounded. It was finally decided in court that Burns must be returned to his master. The law was obeyed; but Boston had been made very angry, and generally her feeling had counted for something in the history of the country. The people draped their houses in mourning and hissed the procession that took Burns to his ship. At the wharf a riot was averted only by a minister's call to prayer. This incident did more to crystallize Northern sentiment against slavery than any other except the exploit of John Brown, and this was the last time that a fugitive slave was taken out of Boston. Burns himself was afterwards bought from his master by popular subscription. He became a free citizen of Boston, and ultimately a Baptist minister in Canada.

Anthony Burns, A Short History of the American Negro (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1919), 81-82.

Anthony Burns (Appleton’s)

Reference

BURNS, Anthony, fugitive slave, b. in Virginia about 1830; d. in St. Catharines, Canada, 27 July, 1862. He effected his escape from slavery in Virginia, and was at work in Boston in the winter of 1853-'4. On 23 May, 1854, the U. S. house of representatives passed the Kansas-Nebraska bill repealing the Missouri compromise, and permitting the extension of negro slavery, which had been restricted since 1820. The news caused great indignation throughout the free states, especially in Boston, where the anti-slavery party had its headquarters. Just at this crisis Burns was arrested by U. S. Marshal Watson Freeman, under the provisions of the fugitive-slave act, on a warrant sworn out by Charles F. Suttle. He was confined in the Boston court-house under a strong guard, and on 25 May was taken before U. S. Commissioner Loring for examination. Through the efforts of Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker, an adjournment was secured to 27 May, and in the mean time a mass-meeting was called at Faneuil hall, and the U. S. marshal summoned a large posse of extra deputies, who were armed and stationed in and about the court-house to guard against an expected attempt at the rescue of Burns. The meeting at Faneuil hall was addressed by the most prominent men of Boston, and could hardly be restrained from adjourning in a body to storm the court-house. While this assembly was in session, a premature attempt to rescue Burns was made under the leadership of Thomas W. Higginson. A door of the courthouse was battered in, one of the deputies was killed in the fight, and Col. Higginson and others of the assailants were wounded. A call for re-enforcements was sent to Faneuil hall, but in the confusion it never reached the chairman. On the next day the examination was held before Commissioner Loring, Richard H. Dana and Charles M. Ellis appearing for the prisoner. The evidence showed that Burns was amenable under the law, and his surrender to his master was ordered. When the decision was made known, many houses were draped in black, and the state of popular feeling was such that the government directed that the prisoner be sent to Virginia on board the revenue cutter “Morris.” He was escorted to the wharf by a strong guard, through streets packed with excited crowds. At the wharf the tumult seemed about to culminate in riot, when the Rev. Daniel Foster (who was killed in action early in the civil war) exclaimed, “Let us pray !” and silence fell upon the multitude, who stood with uncovered heads, while Burns was hurried on board the cutter. A more impressively dramatic ending, or one more characteristic of an excited but law-abiding and God-fearing New England community, could hardly be conceived for this famous case. Burns afterward studied at Oberlin college, and eventually became a Baptist minister, and settled in Canada, where, during the closing years of his life, he presided over a congregation of his own color. See “Anthony Burns, A History,” by С. Е. Stevens (Boston, 1854).

James Grant Wilson and John Fiske, eds., “Burns, Anthony,” Appleton’s Cyclopaedia of American Biography (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1888), 1: 460.

Anthony Burns (Notable Americans)

Reference

BURNS, Anthony, fugitive slave, was born in Virginia about 1830. When twenty years old he made his escape and reached Boston, where he worked during the years 1853-'54. The fugitive slave law which had recently been signed by President Fillmore made possible his arrest, May 24, 1854. Burns was confined in the court house and his trial was opened on the morning of May 25, Richard Ы. Dana, Jr., Charles M. Ellis, and Robert Morris volunteering as his counsel. The case was adjourned to the 27th, and on the 26th a mass meeting was held in Faneuil Hall, which was addressed by Judge Russell, Theodore Parker, and Wendell Phillips; when news that a mob had gathered around the court house reached Faneuil Hall the meeting dissolved and its excited members rushed there. A door was forced, and in the struggle that followed one Bachelder was killed, while others were wounded, among them Rev. Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Finding the court house garrisoned by marines and soldiers, the besiegers retreated. On the 27th overtures were made to Colonel Suttle for the purchase of Burns. The colonel agreed to part with him for the sum of twelve hundred dollars, provided the money was tendered before 12 o'clock, P.M., May 27. The money and pledges were provided by the exertions of L. A. Grimes, pastor of the church for colored people, and the deed of manumission needed only the signature of the marshal, which he was prevented from affixing by District-Attorney Hallett. A decision was given by the commissioners, June 2, in favor of the slaveowner, and Burns was marched to the wharf surrounded by soldiers. There were fifty thousand spectators, but no attempt at rescue was made, the streets being lined with soldiers. ' In State street the windows were draped with black, a coffin inscribed with the legend, " The Funeral of Liberty," was suspended from a window opposite the old state house, and a U. S. flag was hung across the street draped with black and with the Union down. Burns was placed on board a U. S. cutter and taken to Richmond, when he was fettered and confined in a slave pen for four months, and treated with loathsome cruelty. He was then sold to a Mr. McDaniel, of North Carolina, who is entitled to credit for the kindness with which he treated Burns, and the resolute help he gave in restoring him to his friends at the north. The twelfth Baptist church in Boston, of which Burns was a member, purchased his freedom through the contributions made by the citizens. He returned to Boston, and by the benevolence of a lady was given a scholarship at Oberlin in1855; from there he entered Fairmont institute. In 1860 he was put in charge of the colored Baptist church in Indianapolis, but under the threat of the enforcement of the Black laws; with penalty of fine and imprisonment, he remained there only three weeks. Not long after he found a field of labor at St. Catherine's, Canada, where he worked with commendable zeal until his death, July 27, 1862.

Rossiter Johnson, ed., The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans (Boston: The Biographical Society, 1904).

Anthony Burns (Brown, 1986)

Reference

Within the northern United States, a number of fights and riots occurred when slave catchers tried to return blacks to their masters. For example, in 1854 in Boston, slave catchers seized Anthony Burns, an escaped slave. It took marines, cavalry and artillery to hold back the thousands of people who tried to keep Burns from being returned to his Southern master. The attempt to free him failed. Nevertheless, a few months after his return to the South, Northern abolitionists purchased Anthony Burns from his master and sent him to Canada.

Richard C. Brown and Herbert J. Bass, One Flag One Land, vol. 1 (Morristown, NJ: Silver Burdett Company, 1986), 465.

Anthony Burns (Chicago Tribune)

Obituary

Death of Anthony Burns, the Fugitive Slave.

Anthony Burns, the fugitive slave who was arrested in Boston in 1854, remanded to bondage, and [afterward] redeemed, died at St. Catherines, Canada West, on the 27th of July. His disease was consumption, acquired by exposure while trying to clear from debt the church of which he was pastor. The Rev. Hiram Wilson gives the following notice of the deceased:

The concourse around his peaceful grave were mostly colored, the adults of whom, like himself, had fled from bondage; and yet there was quite a number of white people of various churches and different nationalities. While there consigning his mortal remains to the silent dust. I thought of the awful excitement a few years ago in Boston, attending on his arrest and rendition to the hands of bloody men, who are in open rebellion against the government, and against God and humanity.

I seemed to have a sort of panoramic vision of the pro-slavery treachery, the arrest, the court proceedings, the mass meetings, the vast army of marshals and of the military, and the countless throngs of people blocking up the streets of Boston— his dark and awful doom as a victim of the fugitive slave law, and the hellish exultations of the slave power on the one hand—while lamentations spread all over the coasts of New England and rolled back to the Rocky Mountains. I thought of the iniquitous system as having culminated to the awful crisis now hanging over the American people. The name of Anthony Burns fills an important place in the history of events which led to the great conflict now pending between the marshaled hosts of freedom and the fiendish friends and minions of slavery, and will be pronounced which honor when the fetters shall have fallen from the limbs of millions of his suffering brethren. Brother Burns was much respected in this quarter. Since he left Oberlin and came over into Canada he has made good impressions where he lectured in various places.

Anthony Burns, the fugitive slave who was arrested in Boston in 1854, remanded to bondage, and [afterward] redeemed, died at St. Catherines, Canada West, on the 27th of July. His disease was consumption, acquired by exposure while trying to clear from debt the church of which he was pastor. The Rev. Hiram Wilson gives the following notice of the deceased:

The concourse around his peaceful grave were mostly colored, the adults of whom, like himself, had fled from bondage; and yet there was quite a number of white people of various churches and different nationalities. While there consigning his mortal remains to the silent dust. I thought of the awful excitement a few years ago in Boston, attending on his arrest and rendition to the hands of bloody men, who are in open rebellion against the government, and against God and humanity.

I seemed to have a sort of panoramic vision of the pro-slavery treachery, the arrest, the court proceedings, the mass meetings, the vast army of marshals and of the military, and the countless throngs of people blocking up the streets of Boston— his dark and awful doom as a victim of the fugitive slave law, and the hellish exultations of the slave power on the one hand—while lamentations spread all over the coasts of New England and rolled back to the Rocky Mountains. I thought of the iniquitous system as having culminated to the awful crisis now hanging over the American people. The name of Anthony Burns fills an important place in the history of events which led to the great conflict now pending between the marshaled hosts of freedom and the fiendish friends and minions of slavery, and will be pronounced which honor when the fetters shall have fallen from the limbs of millions of his suffering brethren. Brother Burns was much respected in this quarter. Since he left Oberlin and came over into Canada he has made good impressions where he lectured in various places.

“Obituary: Death of Anthony Burns...” Chicago (IL) Tribune, September 2, 1862, p. 3: 4.