Record Data

Transcription

The Crisis and Its Solution.

“There is at last a gleam of sunshine,” said a telegraphic dispatch published yesterday from Washington. This gleam of sunshine proceeded from a rumor that Jefferson Davis has received a despatch from the President elect, stating that he was preparing a letter for publication defining his position upon the questions now distracting the two sections of the country – a letter which, it was believe, would give entire satisfaction to the South.

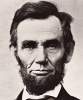

Whether there be any truth in this statement or not, Mr. Lincoln owes it to himself and to his country to make it true as soon as possible. There is no man in this Union more deeply interested in its fate than he is, and upon the course he many now pursue – not the policy he may adopt after his inauguration – hangs his own future weal or woe. Upon what he will do or not do within the next few days may depend whether he will have reason to curse the day he was born, or whether he will “rise to the height of the great argument,” and, ignoring all party considerations in the presence of the danger which looms up before his eyes in such colossal proportions, prove himself a statesman, and save the country by coming our with a clear and distinct programme of his views upon the crisis, and of the action which he would recommend to Congress and the country in this hour or peril and dismay. Before the Colleges of Electors chosen by the people to elect a President had met in their several States to cast their votes Mr. Lincoln might have had some delicacy about presenting his ideas to the people, but now that they have assembled and placed his election beyond all peradventure, etiquette no longer imposes silence upon him. On the contrary, it is now his imperative duty, as the President elect, to declare the policy by which his administration will be guided. It is his election by a sectional party at the North, whose purpose it is to overthrow the institutions of the South, which is proclaimed to be the provocation to the present revolutionary condition of the Cotton States, the source of commercial embarrassment which now exists in two worlds, and the cause of all the present distress and gloomy prospects which hang like a black cloud over the future of the country.

What is the present critical condition of the country? The effects of the revolution, thus far, may be classed under the following heads: -

1. The closing of factories and the discharge of labor everywhere.

2. The depreciation of stocks, national and State, railroad and bank.

3. Depreciation in the value of cotton, wool, flour, grain and other products of the soil.

4. Depreciation in the value of negroes and real estate.

The loss already sustained throughout the country by this sudden prostration of trade and industry cannot fall far short of two hundred millions of dollars! But this is not all. Other disastrous effects are soon to follow.

First. The rebound from Europe foreshadowed by the news by the Asia.

Secondly. The stoppage of probably all the mills and workshops of the country, thowing a million or more of free laborers out of employment in the depths of winter.

Thirdly. The consequent suffering and anarchy everywhere, but especially at the North, where labor is compelled to take care of itself.

For this state of things what remedies have been proposed?

First. The repeal of the Personal Liberty laws.

Second. A national convention to give new guarantees to the South, including the extension of the Missouri line of compromise to the Pacific.

Third. The appointment of a committee of thirty-three in the House of Representatives to take into consideration the President’s Message.

But what have the republicans done as a party? Absolutely nothing. When Thurlow Weed declared for concession he was cried down by republican journals and party leaders. Individual efforts have been made, but what are they? Vermont has referred her Personal Liberty bill to a committee of three conservative lawyers for their opinion as to its unconstitutionality, which probably is a virtual repeal of the law. Governor Banks, it is said, will recommend the repeal of the Massachusetts law in his message next moth. Other Northern States will probably repeal their Personal Liberty laws when their Legislatures meet. Such partial concessions as these may be made here and there. But the republican party, as such, have done nothing as yet to arrest the progress of disunion. If there be any statesmen or patriots in that party it is now necessary for them to take the initiative towards the settlement of the great question which agitates the public mind. The whole Southern people are united in their demand for new guarantees. South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, are now in a state of incipient revolution. North Carolina, Louisiana, Texas and Arkansas are on the verge of it, and soon may cross the Rubicon. The Governor of Tennessee, one of the most conservative States of the South, has called an extra session of the Legislature to consider the question of the day. The other Southern States will soon follow the example of Tennessee.

Now the people of the South have always been, with exceptions of course, a Union-loving people. They know how to appreciate the benefits they derive from the confederation, with its railroads and telegraphs, its rivers, its canals, and all its inter-State interests, both natural and artificial. Their hearts thrill with the historic glories of the Union, and nothing but a feeling of dire necessity could drive them beyond its pale. There is one man in this crisis of our national affairs, who, if he has the capacity, can stay the progress of revolution, and reunite the antagonistic sections of this country into one harmonious people, who in future will “know no North, no South, no East, no West.” All eyes turn to Abraham Lincoln. His party is demoralized and disorganized. Let him throw off its feeble shackles and give form and substance to the conservative sentiments by which his friends say he is animated. Great emergencies prove the ability of the statesman. Will the President elect seize the opportunity, or let it pass away forever?