Record Data

Transcription

UNITED STATES STEAMER SAN JACINTO

At sea, November 16, 1861

Sir : In my despatch by Commander Taylor I confined myself to the report of the movements of this ship and the facts connected with the capture of Messrs. Mason, Slidell, Eustis and McFarland, as I intended to write you particularly relative to the reasons which induced my action in making them prisoners.

When I heard at Cienfuegos, on the south side of Cuba, of these commissioners having landed on the Island of Cuba, and that they were at the Havana, and would depart in the English steamer of the 7th November, I determined to intercept them, and carefully examined all the authorities on international law to which I had access, viz.: Kent, Wheaton, and Vattel, beside various decisions of Sir William Scott, and other judges of the admiralty court of Great Britain, which bore upon the rights of neutrals and their responsibilities.

The Governments of Great Britain, France, and Spain, having issued proclamations that the Confederate States were viewed, considered, and treated as belligerents, and knowing that the ports of Great Britain, France, Spain, and Holland in the West Indies, were open to their vessels, and that they were admitted to all the courtesies and protection vessels of the United States received, every aid and attention being given them, proved clearly that they acted upon this view and decision, and brought them within the international law of search and under the responsibilities. I therefore felt no hesitation in boarding and searching all vessels of whatever nation I fell in with, and have done so.

The question arose in my mind whether I had the right to capture the persona of these commissioners — whether they were amenable to capture. There was no doubt I had the right to capture vessels with written despatches; they are expressly referred to in all authorities, subjecting the vessel to seizure and condemnation if the captain of the vessel had the knowledge of their being on board; but these gentlemen were not despatches in the literal sense, and did not seem to come under that designation, and nowhere could I find a case in point.

That they were commissioners I had ample proof from their own avowal, and bent on mischievous and traitorous errands against our country, to overthrow its institutions, and enter into treaties and alliances with foreign States, expressly forbidden by the Constitution.

They had been presented to the captain-general of Cuba by her Britannic Majesty's consul-general, but the captain-general told me that he had not received them in that capacity, but as distinguished gentlemen and strangers.

I then considered them as the embodiment of despatches; and as they had openly declared themselves as charged with all authority from the Confederate Government to form treaties and alliances tending to the establishment of their independence, I became satisfied that their mission was adverse and criminal to the Union, and it therefore became my duty to arrest their progress and capture them if they had no passports or papers from the Federal Government, as provided for under the law of nations, viz.: "That foreign ministers of a belligerent on board of neutral ships are required to possess papers from the other belligerent to permit them to pass free."

Report and assumption gave them the title of ministers to France and England ; but inasmuch as they had not been received by either of these powers, I did not conceive that they had any immunity attached to their persons, and were but escaped conspirators, plotting and contriving to overthrow the Government of the United States, and they were therefore not to be considered as having any claim to the immunities attached to the character they thought fit to assume.

As respects the steamer in which they embarked, I ascertained in the Havana that she was a merchant vessel plying between Vera Cruz, the Havana, and St. Thomas, carrying the mail by contract.

The agent of the vessel, the son of the British consul at Havana, was well aware of the character of these persons; that they engaged their passage and did embark in the vessel; his father had visited them and introduced them as ministers of the Confederate States on their way to England and France.

They went in the steamer with the knowledge and by the consent of the captain, who endeavored afterward to conceal them by refusing to exhibit his passenger list, and the papers of the vessel. There can be no doubt he knew they were carrying highly important despatches, and were endowed with instructions inimical to the United States. This rendered his vessel (a neutral) a good prize, and I determined to take possession of her, and, as I mentioned in my report, send her to Key West for adjudication, where, I am well satisfied, she would have been condemned for carrying these persons, and for resisting to be searched. The cargo was also liable, as all the shippers were knowing to the embarkation of these live despatches, and their traitorous motives and actions to the Union of the United States.

I forbore to seize her, however, in consequence of my being so reduced in officers and crew, and the derangement it would cause innocent persons, there being a large number of passengers who would have been put to great loss and inconvenience, as well as disappointment, from the interruption it would have caused them in not being able to join the steamer from St. Thomas to Europe. I therefore concluded to sacrifice the interests of my officers and crew in the prize, and suffered the steamer to proceed, after the necessary detention to effect the transfer of these commissioners, considering I had obtained the important end I had in view, and which affected the interests of our country and interrupted the action of that of the Confederates.

I would add that the conduct of her Britannic Majesty's subjects, both official and others, showed but little regard or obedience to her proclamation, by aiding and abetting the views and endeavoring to conceal the persons of these commissioners.

I have pointed out sufficient reasons to show you that my action in this case was derived from a firm conviction that it became my duty to make these parties prisoners, and to bring them to the United States.

Although in my giving up this valuable prize I have deprived the officers and crew of a well-earned reward, I am assured they are quite content to forego any advantages which might have accrued to them under the circumstances.

I may add that, having assumed the responsibility, I am willing to abide the result

I am, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

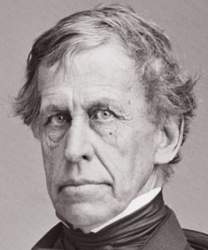

Charles Wilkes,

Captain

Hon. Gideon Welles

Secretary of the Navy.