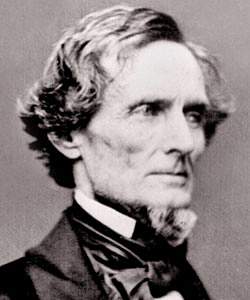

Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy (American National Biography)

Scholarship

Davis built a powerful central government. He saw himself as a strict constructionist but never doubted that the Confederate Constitution gave him war powers that were necessary in the crisis. From the first he insisted that state troops come under the central government's control, and when four state governors sought the return of state-owned arms he declared in disgust that "if such was to be the course of the States . . . we had better make terms as soon as we could." Despite enormous local pressures, Davis insisted that "the idea of retaining in each State its own troops for its own defense" was a "fatal error. . . . Our safety--our very existence--depends on the complete blending of the military strength of all the States into one united body, to be used anywhere and everywhere as the exigencies of the contest may require."

Paul D. Escott, "Davis, Jefferson," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/04/04-00300.html.

Jefferson Davis, Conscription (American National Biography)

Scholarship

After only one year of war he sought and obtained a power unprecedented in American history: conscription. The idea of compelling men to fight in the armies was anathema to some southerners and generated fierce protests from political leaders such as Governor Joseph Emerson Brown of Georgia. But Davis was convinced that the Confederacy could not survive without conscription, for, as Secretary of War James Seddon later admitted, "the spirit of volunteering had died out." Davis answered Brown's protests unflinchingly and argued for a Hamiltonian interpretation of the Constitution's "necessary and proper" clause. In another restriction of personal liberties Davis requested and obtained the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus on repeated occasions to deal with disloyalty in threatened areas. Although he scrupulously refrained from acting without congressional authority, he urged what he believed necessary even in the face of criticism.

Paul D. Escott, "Davis, Jefferson," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/04/04-00300.html.

Jefferson Davis, Emancipation (American National Biography)

Scholarship

The Confederate president's flexibility on slavery and commitment to independence emerged clearly late in the war, when he proposed arming and freeing the South's slaves. It is likely that Davis considered this possibility earlier, but he had hoped to influence the 1864 northern elections and could not afford a well-publicized, divisive debate within the South. After Lincoln's reelection, however, he straightforwardly argued that slavery was less important than independence and that slaves would fight and deserved freedom as a reward. These proposals aroused enormous opposition, but as was usually the case, Davis won Congress's approval for most of his plan.

Paul D. Escott, "Davis, Jefferson," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/04/04-00300.html.

Jefferson Davis, Collapse of the Confedaracy (American National Biography)

Scholarship

The common people of the Confederacy grew disaffected not for ideological reasons, but because their conditions of life became intolerable. Often they favored stronger government action if it would alleviate suffering. Impoverished soldiers' families also resented the privileges enjoyed by planters, particularly those related to the draft, such as the exemption of overseers and the ability of those with means to hire a substitute. The combination of poverty and resentment over a "rich man's war and a poor man's fight" nourished a growing stream of desertions from the Confederate ranks. To these problems Davis was largely insensitive. He allowed inequitable policies to become law, and later, when more perceptive officials such as Commissioner of Taxes Thompson Allen or Secretary of War James Seddon urged measures to alleviate distress, he concluded that resources were too limited to allow action. His neglect of the common people's suffering led directly to military weakness...After the Civil War Davis was imprisoned for two years at Fortress Monroe in Hampton Roads. Despite damage to his health, he survived and carried himself through the postwar years as a defeated but unrepentant Confederate.

Paul D. Escott, "Davis, Jefferson," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/04/04-00300.html.

Jefferson Davis (Congressional Biographical Directory)

Reference

DAVIS, Jefferson, (son-in-law of President Zachary Taylor), a Representative and a Senator from Mississippi; born in what is now Fairview, Todd County, Ky., June 3, 1808; moved with his parents to a plantation near Woodville, Wilkinson County, Miss.; attended the country schools, St. Thomas College, Washington County, Ky., Jefferson College, Adams County, Miss., Wilkinson County Academy, and Transylvania University, Lexington, Ky.; graduated from the United States Military Academy, West Point, N.Y., in 1828; served in the Black Hawk War in 1832; promoted to the rank of first lieutenant in the First Dragoons in 1833, and served until 1835, when he resigned; moved to his plantation, ‘Brierfield,’ in Warren County, Miss., and engaged in cotton planting; elected as a Democrat to the Twenty-ninth Congress and served from March 4, 1845, until June 1846, when he resigned to command the First Regiment of Mississippi Riflemen in the war with Mexico; appointed to the United States Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Jesse Speight; subsequently elected and served from August 10, 1847, until September 23, 1851, when he resigned; chairman, Committee on Military Affairs (Thirtieth through Thirty-second Congresses); unsuccessful candidate for Governor in 1851; appointed Secretary of War by President Franklin Pierce 1853-1857; again elected as a Democrat to the United States Senate and served from March 4, 1857, until January 21, 1861, when he withdrew with other secessionist Senators; chairman, Committee on Military Affairs and the Militia (Thirty-fifth and Thirty-sixth Congresses); commissioned major general of the State militia in January 1861; chosen President of the Confederacy by the Provisional Congress and inaugurated in Montgomery, Ala., February 18, 1861; elected President of the Confederacy for a term of six years and inaugurated in Richmond, Va., February 22, 1862; captured by Union troops in Irwinsville, Ga., May 10, 1865; imprisoned in Fortress Monroe, indicted for treason, and was paroled in the custody of the court in 1867; returned to Mississippi and spent the remaining years of his life writing; died in New Orleans, La., on December 6, 1889; interment in Metairie Cemetery, New Orleans, La.; reinterment on May 31, 1893, in Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Va.; the legal disabilities placed upon him were removed, and he was posthumously restored to the full rights of citizenship, effective December 25, 1868, pursuant to a Joint Resolution of Congress (Public Law 95-466), approved October 17, 1978.

“Davis, Jefferson,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774 to Present, http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=D000113.

Jefferson Davis (Dictionary of United States History)

Reference

Davis, Jefferson (June 3, 1808-December 6, 1889), President of the Southern Confederacy, was born in Kentucky, and graduated at West Point in 1828. He saw some service in the Black Hawk War, but resigned from the army and became a cotton planter in Mississippi. He represented that State in Congress in 1845-46, but left Congress to take part as colonel in the Mexican War. In the storm of Monterey and the battle of Buena Vista he distinguished himself and was straightway chosen to the U. S. Senate, where he served 1847-51 and 1857-61. In 1851 he ran unsuccessfully as the States-rights candidate for Governor of Mississippi. In President Pierce's administration Mr. Davis was the Secretary of War 1853-57. He had become one of the Southern leaders, received some votes for the Democratic nomination for President in 1860, and in January, 1861, he left the U. S. Senate. He was thereupon elected provisional President of the Confederacy February 9, 1861, and was inaugurated February 18. In November of the same year he was elected President and was inaugurated February 22, 1862. From the second year of the war till the close many of his acts were severely criticised in the South itself. Many Southerners admit that President Davis' actions, especially his interference in military matters, impaired the prospects of success. An instance in point was his removal of General J. E. Johnston from command in 1864. Early in 1865 he conducted unsuccessful negotiations for peace. On the second of April the successes of Grant's army obliged President Davis to leave Richmond; he took the train for Danville, and after consultation proceeded southward and was captured by the Federals near Irwinsville, Ga., May 10, 1865. Until 1867 he was confined as a prisoner in Fort Monroe. He was in 1866 indicted for treason, released on bail the following year, and the trial was dropped. He passed the remainder of his life at Memphis and later in Mississippi, dying in New Orleans. He is the author of "Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government," two volumes. There are lives by Pollard and Alfriend.

J. Franklin Jameson, "Davis, Jefferson," Dictionary of United States History, 1492-1895 (Boston: Puritan Publishing Co., 1894), 186.

Jefferson Davis (American Cyclopaedia)

Reference

DAVIS, Jefferson, an American soldier and statesman, born June 3, 1808, in that part of Christian co., Ky., which now forms Todd county. Soon after his birth his father removed to Mississippi, and settled near Woodville, Wilkinson county. Jefferson Davis received an academical education, and was sent to Transylvania college, Ky., which he left in 1824, having been appointed by President Monroe a cadet in the military academy at West Point, where he graduated in 1828. He remained in the army seven years, and served as an infantry and staff officer on the N. W. frontier in the Black Hawk war of 1831-'2, and in March, 1833, was made first lieutenant of dragoons, in which capacity he was employed in 1834 in various expeditions against the Comanches, Pawnees, and other hostile Indian tribes. He resigned his commission June 30, 1835, and having married the daughter of Zachary Taylor, afterward president of the United States, but at that time a colonel in the army, he returned to Mississippi, and became a cotton planter. For several years he lived in retirement, occupied chiefly with study. In 1843 he began to take an active part in politics on the democratic side, and in 1844 was one of the presidential electors of Mississippi to vote for Polk and Dallas. In 1845 he was elected a representative in congress, and took his seat in December of that year. He bore a conspicuous part in the discussions of the session on the tariff, on the Oregon question, on military affairs, and particularly on the preparations for war against Mexico, and on the organization of volunteer militia when called into the service of the United States. In his speech on the Oregon question, Feb. 6, 1846, he said : "From sire to son has descended the love of union in our hearts, as in our history are mingled the names of Concord and Camden, of Yorktown and Saratoga, of Moultrie and Plattsbnrgh, of Chippewa and Erie, of Bowyer and Guilford, of New Orleans and Bunker Hill. Grouped together, they form a monument to the common glory of our common country; and where is the southern man who would wish that that monument were less by one of the northern names that constitute the mass?" While he was in congress, in July, 1846, the first regiment of Mississippi volunteers, then enrolled for service in Mexico, elected him their colonel. Overtaking the regiment at New Orleans on its way to the seat of war, he led it to reinforce the army of Gen. Taylor on the Rio Grande. He was actively engaged in the attack and storming of Monterey in September, 1846; was one of the commissioners for arranging the terms of the capitulation of that city; and distinguished himself in the battle of Buena Vista, Feb. 23, 1847, where his regiment, attacked by on immensely superior force, maintained their ground for a long time unsupported, while the colonel, though severely wounded, remained in the saddle until the close of the action. At the expiration of the term of its enlistment, in July, 1847, the Mississippi regiment was ordered home; and while on his return he received at New Orleans a commission from President Polk as brigadier general of volunteers, which he declined accepting, on the ground that the constitution reserves to the states respectively the appointment of the officers of the militia, and that consequently their appointment by the federal executive is a violation of the rights of the states. In August, 1847, he was appointed by the governor of Mississippi United States senator to fill a vacancy, and at the ensuing session of the state legislature, Jan. 11, 1848, was unanimously elected to the same office for the residue of the term, which expired March 4, 1851. In 1850 he was reelected for the ensuing full term. In the senate he was chosen chairman of the committee on military affairs, and took a prominent part in the debates on the slavery question, in defense of the institutions and policy of the slave states, and was a zealous advocate of the doctrine of state rights. In September, 1851, he was nominated for governor of Mississippi by the democratic party, in opposition to Henry S. Foote, the candidate of the Union party. He resigned his seat in the senate on accepting the nomination, and was beaten in the election by a majority of 999 votes; a marked indication of his personal popularity in his own state, for at the "convention election," two months before, the Union party had a majority of 7,500...

George Ripely and Charles Anderson Dana, eds., “Davis, Jeferson,” The American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1874), 5: 711-712.

Jefferson Davis (New Orleans Picayune)

Obituary

JEFFERSON DAVIS.

Address of Hon. John W. Daniel Before the Virginia House of Delegates.

RICHMOND, Va., Jan. 26.— Mozart Academy of Music, the larges public hall in the city, was crowded last night with ladies and distinguished citizens of the state to hear Senator John W. Daniel deliver an oration upon the life and character of Jefferson Davis upon invitation of the legislature. Governor McKinney and General Jubal A. Early were among the prominent citizens present.Hon. F. Cardwell, speaker of the house of representatives, introduced Senator Daniel, who said: “Noble are the words of Cicero when he tells us that ‘is is the first and fundamental law of history that it should neither dare to say anything that is false or fear to say anything that is true, nor give any just suspicions of favor or disaffection.

“No less high a standard must be invoked in considering the life, character and services of Jefferson Davis,

A GREAT MAN OF A GREAT EPOCH,

whose name is blended with the renown of American arms and with the civil glories of the cabinet and congress hall—a son of the south who became the head of a confederacy more populous and more extensive than that for which Jefferson wrote the declaration of independence, and commander-in-chief of armies greater than those of which Washington was the general. He swayed senates and led the soldiers of the union, and he stood accused of treason in a court of justice. He saw victory sweep illustrious battle fields and became a native. He ruled millions and was put in chains. Creating a nation he followed its bier and he died a disfranchised citizen.“But though great in many things, he was greatest in that fortune, which, lifting him first to the loftiest height, and casting him hence to the depth of disappointment, found him everywhere the erect and constant friend of truth. He conquered himself and forgave his enemies, but he bent to none but god. Severe scrutiny of his life and character—no public man was ever subjected to sterner ordeals of character of closer scrutiny of conduct; he was in the public gaze for nearly half a century; and in the fate which at last overwhelmed the southern confederacy and its president, official records and private papers fell into the hands of his enemies. Wary eyes now searched to see if he had overstepped the bounds which the laws of war have set to action; and could such evidence be found, wrathful hearts would have cried for vengeance, but though every hiding place was opened and reward was ready for any who would betray

THE SECRETS OF THE CAPTIVE CHIEF,

whose armies were scattered and whose hands were chained—though the sea gave up its dead in the convulsion of his country—there could be found no guilty fact, and accusing tongues were silenced.“Whatever record leaped to light his name could not be stained.

“I could not, indeed, nor would I, divest myself of those identities and partialities which made me on with the people of whom he was the chief in their supreme conflict. But surely if records were stainless and enemies were dumb, and if the principals pronounce now favorable judgment upon the agent notwithstanding that he failed, there can be no suspicion of undue favor on the part of those who do him honor, and the contrary inclination could only spring from disaffection.

“The people of the south knew Jefferson Davis. He mingled his daily life with theirs under the eager kin of those who had bound up with him all that life can cherish.

“To his hands they consigned their destinies and under his guidance they committed the land they loved with husbands, fathers, sons and brothers to the God of battles.

“Ruin, wounds and death became their portion, and yet they do declare that Jefferson Davis was

AN UNSELFISH PATRIOT,

and a noble gentleman; that as the trustee of the highest trust that man can place in man, he was clear and faithful, and that in his office he exhibited those grand heroic attributes which were worthy of its dignity and their struggles for independence. Thus it was that when the news came that he was no more there was no southern house that did not pass under the shadow of affliction. Thus it was that the governors of commonwealths bore his body to the tomb and that multitudes gathered from afar to bow in reverence. Thus it was that throughout the south the scarred soldiers, the widowed wives, the kindred of those who had died in the battle which he delivered, met to give the utterance to their respect and sorrow. Thus it was that the general assembly of Virginia is now convened to pay their tribute. Completer testimony to human worth was never given and thus it will be that the south will build a monument to record their verdict that he was true to his people, his conscience and his God, and no stone that covers the dead will be worthier of the Roman legend: Clarus et vir fortissimus.Senator Daniel’s speech consumed about two hours in its delivery.

“Jefferson Davis,” New Orleans (LA) Picayune, January 27, 1890, p. 1: 5.