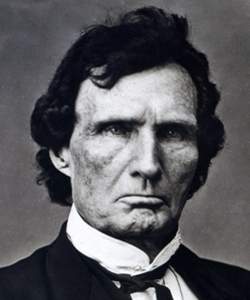

Thaddeus Stevens (Congressional Biographical Directory)

Reference

STEVENS, Thaddeus, a Representative from Pennsylvania; born in Danville, Caledonia County, Vt. April 4, 1792; attended Peacham Academy and the University of Vermont at Burlington; was graduated from Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., in 1814; moved to Pennsylvania in 1814; studied law; was admitted to the bar in 1816 and commenced practice in Gettysburg; member of the State house of representatives 1833-1835, 1837, and 1841; delegate to the State constitutional convention in 1838; appointed as a canal commissioner in 1838; moved to Lancaster, Pa., in 1842; elected as a Whig to the Thirty-first and Thirty-second Congresses (March 4, 1849-March 3, 1853); elected as a Republican to the Thirty-sixth and to the four succeeding Congresses and served from March 4, 1859, until his death; chairman, Committee on Ways and Means (Thirty-seventh and Thirty-eighth Congresses), Committee on Appropriations (Thirty-ninth and Fortieth Congresses); chairman of the managers appointed by the House of Representatives in 1868 to conduct the impeachment proceedings against Andrew Johnson, President of the United States; died in Washington, D.C., on August 11, 1868; interment in Shreiner’s Cemetery, Lancaster, Pa.

“Stevens, Thaddeus,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774 to Present, http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=S000887.

Thaddeus Stevens, Reconstruction (American National Biography)

Scholarship

The end of the war presented the Republican party with several distinct policy options, the most radical of which was pioneered by Stevens. Arguing that the southern states were conquered territories, outside of the Union, without constitutional protections, and subject to direct congressional governance, he proposed a wide-reaching land redistribution program aimed at breaking the economic and political influence of the planter elite and creating an independent black yeomanry. Like most of his contemporaries, he understood civil rights as entailing equality under the law and equal opportunity for self-advancement, but he viewed the enfranchisement of freedmen as a privilege and not a right, beyond congressional authority and secondary in importance to the socioeconomic restructuring of the South.

In 1866 and 1867 Stevens found himself forced to juggle dual roles as House leader and Radical chieftain. He forged a precarious balance between compromise and principle. When his land redistribution program was defeated in February 1866, he accepted the party's moderate course and defended the Freedmen's Bureau and civil rights bills against presidential opposition. Later that year he shepherded the relatively moderate Fourteenth Amendment, parts of which he had authored, through the House. Although he viewed these measures as incomplete, he counseled his fellow Radicals to "take what we can get now and hope for better things in further legislation" (Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st sess., p. 3148).

In 1866 and 1867 Stevens found himself forced to juggle dual roles as House leader and Radical chieftain. He forged a precarious balance between compromise and principle. When his land redistribution program was defeated in February 1866, he accepted the party's moderate course and defended the Freedmen's Bureau and civil rights bills against presidential opposition. Later that year he shepherded the relatively moderate Fourteenth Amendment, parts of which he had authored, through the House. Although he viewed these measures as incomplete, he counseled his fellow Radicals to "take what we can get now and hope for better things in further legislation" (Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st sess., p. 3148).

Josh Zeitz, "Stevens, Thaddeus," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/04/04-00953.html.

Thaddeus Stevens, Relationship with Lydia Hamilton Smith (Trefousse, 1997)

Scholarship

And before long, [Thaddeus Stevens] obtained the services of a housekeeper, Lydia Hamilton Smith, a mulatto widow of great respectability with two children, who remained with him and took care of him for the rest of his life. Thad’s relations with Mrs. Smith have given rise to never ending speculation. Widely thought to be his mistress, both at the time and afterward, Mrs. Smith was treated with great respect by Stevens’s family and by himself. He always addressed her as “Madam,” gave her his seat in public conveyances, and included her in social intercourse with his friends. As William M. Hall remembered, she was regarded as a “virtuous and respectable woman.” “Certainly,” he commented, “whatever may have been the state of affairs at the inception of the relationship it existed for years at Washington in such form as to leave no discredit connected with it in the minds of Mr. Stevens’s acquaintances and friends and of the general public.”…Stevens himself never confirmed or denied it. In a largely noncommittal letter to W. B. Mellius in September 1867, in which he stressed the fact that he seldom responded to the many attacks upon him, he also stated that the libels concerning his domestic history were “totally without foundation.”

Hans L. Trefousse, Thaddeus Stevens: Nineteenth-Century Egalitarian (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 69-70.