Record Data

Source citation

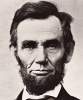

Richard W. Thompson to Abraham Lincoln, June 12, 1860, Washington, DC, Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress, http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/alhtml/malhome.html.

Type

Letter

Date Certainty

Exact

Transcriber

Transcribed by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College, Galesburg, IL

Adapted by Don Sailer, Dickinson College

Transcription date

Transcription

The following transcript has been adapted from the Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress.

Washington City

June 12. 1860

My dear Sir

I have to day received your letter of the 26th Ult; which has been forwarded to me from home.

Of course I did not expect that my kindly expressions of regard for you would be considered of importance enough to be conveyed to you -- but they are none the less sincere on that account. They have always existed in my mind since our first acquaintance, & are such as no mere political disagreements can alienate or abate. So that whether those disagreements exist or not, you may feel entirely satisfied of always having justice done at my hands.

I frankly say to you that I was gratified at your nomination -- especially so, for two reasons-- First, because of my personal regard for you, & second, because I considered it an important step towards conservatism on the part of those who composed the Chicago Convention. There are far more points of agreement than of disagreement between you & me -- & the latter are only those which arise out of the Slavery question -- for apart from that you & I are as good Whigs, I suppose, as we ever were. I mean to defend you at all times against the villianous assaults of the Democracy about your votes in Congress on the subject of the War with Mexico &,c, because I voted with you & have not repented of it. And I apprehend too, if the Slavery question were out of the way, we should have no difficulty in acting in perfect harmony. Individually I do not think we should have much any how -- for the most of these questions are mere abstractions. The greater part of the difficulty arises out of the relation which others bear to you, rather than out of any thing connected with yourself individually. Ever since your nomination I have said, & shall continue to say, that I am not afraid to trust you with the Government, & that if the issue shall be between you and any democrat, I hope you will be elected. I said this in Virginia the other day, & the Whigs there generally approved the sentiment. My deliberate conviction is that this government is gradually sinking into decay under the blighting influences of democracy, & that it is the duty of all of us to defeat them. This has always been my opinion. In 1856 I could not do otherwise than as I did. Fillmore was in the field & those who nominated Fremont aided in his nomination -- except that portion of them who represented the ultraism of Republicanism & which was a small minority. Under these circumstances they commenced a galling fire upon us & we could do no otherwise than fight it out. The Republicans have, in a great measure, kept this fire up upon me pretty much ever since, notwithstanding I have had no active participation in politics; -- but be assured that I shall not hold you, in any degree, responsible for this. And I may say too that it will make no difference in my final determination of the course I shall take in the canvass. From this you will infer that I have not yet decided what to do -- and that is the fact, as it regards one important part of the campaign in Indiana -- that is, the formation of a Bell electoral ticket. I frankly say to you what I have said to Colfax & others that, at present, I am inclined to advise against it -- but shall make no movement in it till after the Balo. Convention & after I reach home -- which will be within ten days I hope. There are a great many things connected with this matter which it would be impossible to put in a letter or to explain unless we could converse together. If that were practicable I should like to explain them to you -- for whatever the result I should deal in perfect frankness with you. This much, however, I will say -- that we have some impracticables in our party who insist upon running an electoral ticket in every state. I have stood pretty much alone in opposition to this -- with a few Southern men to help me -- & have insisted that as our primary object is to beat the democracy we should, by holding off, in the doubtful northern states, let you carry them, so as to break its back in the north, & then make the best fight we can in the South, & if Douglass [Douglas] is the Candidate, break its back also in the South. This will close the career of the monster -- & if it shall result in your election I have endeavored to pursuade our friends that you would select your Cabinet jointly from the north & South & thus inaugurate a Conservative & national administration, which, the Slavery question out of the way, would bring about the restoration of Whiggery. I dont make this remark with a view to induce any promise from you upon this subject, for I have chosen to base my declaration upon my personal knowledge of you -- & shall continue to do so. The work is somewhatup-hill at present, but I have not despaired of success. I learned from a Pennsylvania friend to day that there would probably be no Bell electoral ticket in that state. But these things are hard to manage amongst so many men of discordant views, & have to be conducted, as you know, with great caution. The great trouble in dealing with politicians now a days is, that it is impossible almost to find a man whose patriotism extends beyond his congressional district or the precincts of his office. They decide almost every thing as they are themselves advanced or injured by the decision. But I apprehend that your present position will make you quite familiar with this class, & that if you become President you will have to endure their annoyances.

But I find myself writing to you pretty much as I would talk to you if we were together, & just as if I were really a politician. I do not feel myself to be so. When I left Congress & declined the foreign mission tendered to me by Gen Taylor, I made up my mind never again to hold office of any sort, & shall keep that determination. Hence, I feel myself to be in a condition to act with reference only to what I believe to be the good of the Country -- & the good of the Country requires me to knock democracy as many hard blows as I can.

Now you must not infer from the above that I shall vote for you -- although it should turn out that we should have no electoral ticket in Indiana. That I may do so, is possible -- but if we have no ticket you will carry the State without my vote. And I may withhold it, while at the same time, I should prefer you to carry it -- & yet be perfectly consistent. This I will explain, although I had no idea when I began that I was going to write such a letter as this. My Union friends in the South insist that I must go to the South to help them & that I can do them more good than any other man from the north. Now, if I were to declare myself for you & then go there, you will see that my influence would be lessened. While if I still hold my position in the Union party & let your men have a fair field at the common enemy at the north, I can help more effectively to strangle him at the South. I hope that I have made this plain enough for you to comprehend my meaning.

I do'nt know whether this long letter will furnish any information that you care about, but after I begin it, intending to say but little, I felt a recollection of "Auld Lang Syne" revive in my mind, & could not resist the inclination to dash off a little chit-chat with you. I hope to have a real one with you some of these days, & if you shall become President will come here to your inauguration, just to see how the Presidential robes sit upon you.

Of course I shall be always glad to hear from you -- though you must be greatly troubled by letters now. For God's sake & for your own too, let me beg of you not to write another one for the papers. Let them take you just as you are & as a man takes his wife -- for better or for worse. Letters can do you no good & may do harm. Let them alone -- that is, a[ll?] such as will find their way to the public. I hope you can find time to let me hear from you occasionally. Every thing you think prop[er?] to say to me will be for myself alone. If [I?] think it will interest you, I may occasionally drop you a line about how matters are progressing.

Believe me to be very sincerely

& truly your friend

R. W. Thompson

June 12. 1860

My dear Sir

I have to day received your letter of the 26th Ult; which has been forwarded to me from home.

Of course I did not expect that my kindly expressions of regard for you would be considered of importance enough to be conveyed to you -- but they are none the less sincere on that account. They have always existed in my mind since our first acquaintance, & are such as no mere political disagreements can alienate or abate. So that whether those disagreements exist or not, you may feel entirely satisfied of always having justice done at my hands.

I frankly say to you that I was gratified at your nomination -- especially so, for two reasons-- First, because of my personal regard for you, & second, because I considered it an important step towards conservatism on the part of those who composed the Chicago Convention. There are far more points of agreement than of disagreement between you & me -- & the latter are only those which arise out of the Slavery question -- for apart from that you & I are as good Whigs, I suppose, as we ever were. I mean to defend you at all times against the villianous assaults of the Democracy about your votes in Congress on the subject of the War with Mexico &,c, because I voted with you & have not repented of it. And I apprehend too, if the Slavery question were out of the way, we should have no difficulty in acting in perfect harmony. Individually I do not think we should have much any how -- for the most of these questions are mere abstractions. The greater part of the difficulty arises out of the relation which others bear to you, rather than out of any thing connected with yourself individually. Ever since your nomination I have said, & shall continue to say, that I am not afraid to trust you with the Government, & that if the issue shall be between you and any democrat, I hope you will be elected. I said this in Virginia the other day, & the Whigs there generally approved the sentiment. My deliberate conviction is that this government is gradually sinking into decay under the blighting influences of democracy, & that it is the duty of all of us to defeat them. This has always been my opinion. In 1856 I could not do otherwise than as I did. Fillmore was in the field & those who nominated Fremont aided in his nomination -- except that portion of them who represented the ultraism of Republicanism & which was a small minority. Under these circumstances they commenced a galling fire upon us & we could do no otherwise than fight it out. The Republicans have, in a great measure, kept this fire up upon me pretty much ever since, notwithstanding I have had no active participation in politics; -- but be assured that I shall not hold you, in any degree, responsible for this. And I may say too that it will make no difference in my final determination of the course I shall take in the canvass. From this you will infer that I have not yet decided what to do -- and that is the fact, as it regards one important part of the campaign in Indiana -- that is, the formation of a Bell electoral ticket. I frankly say to you what I have said to Colfax & others that, at present, I am inclined to advise against it -- but shall make no movement in it till after the Balo. Convention & after I reach home -- which will be within ten days I hope. There are a great many things connected with this matter which it would be impossible to put in a letter or to explain unless we could converse together. If that were practicable I should like to explain them to you -- for whatever the result I should deal in perfect frankness with you. This much, however, I will say -- that we have some impracticables in our party who insist upon running an electoral ticket in every state. I have stood pretty much alone in opposition to this -- with a few Southern men to help me -- & have insisted that as our primary object is to beat the democracy we should, by holding off, in the doubtful northern states, let you carry them, so as to break its back in the north, & then make the best fight we can in the South, & if Douglass [Douglas] is the Candidate, break its back also in the South. This will close the career of the monster -- & if it shall result in your election I have endeavored to pursuade our friends that you would select your Cabinet jointly from the north & South & thus inaugurate a Conservative & national administration, which, the Slavery question out of the way, would bring about the restoration of Whiggery. I dont make this remark with a view to induce any promise from you upon this subject, for I have chosen to base my declaration upon my personal knowledge of you -- & shall continue to do so. The work is somewhatup-hill at present, but I have not despaired of success. I learned from a Pennsylvania friend to day that there would probably be no Bell electoral ticket in that state. But these things are hard to manage amongst so many men of discordant views, & have to be conducted, as you know, with great caution. The great trouble in dealing with politicians now a days is, that it is impossible almost to find a man whose patriotism extends beyond his congressional district or the precincts of his office. They decide almost every thing as they are themselves advanced or injured by the decision. But I apprehend that your present position will make you quite familiar with this class, & that if you become President you will have to endure their annoyances.

But I find myself writing to you pretty much as I would talk to you if we were together, & just as if I were really a politician. I do not feel myself to be so. When I left Congress & declined the foreign mission tendered to me by Gen Taylor, I made up my mind never again to hold office of any sort, & shall keep that determination. Hence, I feel myself to be in a condition to act with reference only to what I believe to be the good of the Country -- & the good of the Country requires me to knock democracy as many hard blows as I can.

Now you must not infer from the above that I shall vote for you -- although it should turn out that we should have no electoral ticket in Indiana. That I may do so, is possible -- but if we have no ticket you will carry the State without my vote. And I may withhold it, while at the same time, I should prefer you to carry it -- & yet be perfectly consistent. This I will explain, although I had no idea when I began that I was going to write such a letter as this. My Union friends in the South insist that I must go to the South to help them & that I can do them more good than any other man from the north. Now, if I were to declare myself for you & then go there, you will see that my influence would be lessened. While if I still hold my position in the Union party & let your men have a fair field at the common enemy at the north, I can help more effectively to strangle him at the South. I hope that I have made this plain enough for you to comprehend my meaning.

I do'nt know whether this long letter will furnish any information that you care about, but after I begin it, intending to say but little, I felt a recollection of "Auld Lang Syne" revive in my mind, & could not resist the inclination to dash off a little chit-chat with you. I hope to have a real one with you some of these days, & if you shall become President will come here to your inauguration, just to see how the Presidential robes sit upon you.

Of course I shall be always glad to hear from you -- though you must be greatly troubled by letters now. For God's sake & for your own too, let me beg of you not to write another one for the papers. Let them take you just as you are & as a man takes his wife -- for better or for worse. Letters can do you no good & may do harm. Let them alone -- that is, a[ll?] such as will find their way to the public. I hope you can find time to let me hear from you occasionally. Every thing you think prop[er?] to say to me will be for myself alone. If [I?] think it will interest you, I may occasionally drop you a line about how matters are progressing.

Believe me to be very sincerely

& truly your friend

R. W. Thompson