Record Data

Source citation

Reprinted in Lieutenant James Stradling, "The Lottery of Death," McClure's Magazine, Vol. XXVI, November to April 1905-1906 (New York: S.S. McClure Company, 1906), 96-98.

Recipient (to)

James Spradling

Type

Letter

Date Certainty

Exact

Transcriber

John Osborne

Transcription date

Transcription

The following text is presented here in complete form, as it originally appeared in print. Spelling and typographical errors have been preserved as in the original.

Mine Gott! Jim, I never felt so weak in all my life as I did when I found I had drawn a 'death prize.' My kind friend Captain Flinn was very pale and much weaker than I ; but we did not have much time to think about it, for a Confederate officer told us that his verbal instructions were to have us executed before noon, and that he would return in an hour, so we asked permission to have a few moments to write letters to our homes, and to our friends before being executed. We were removed to a room by ourselves and furnished with writing material; but we could not compose our nerves or our thoughts sufficiently to write. The Confederate officer was as humane as he could be under the circumstances, and instead of returning in an hour, did not return for two hours. In the meantime we bade our companions farewell, and distributed a few trinkets we had on our persons, and then after confiding to our warmest friends a few messages for our families, we waited as quietly as we could, the coming of the death summons. We did not have very long to wait, for soon a Confederate officer appeared with a guard, and Flinn and I were marched to the street where we found a cart waiting for us. We took our seats in the cart, and the Confederate officer and the guard of cavalry escorted us through the streets of Richmond. The cart, if I remember rightly, was drawn by oxen, and it did not move very fast, but a thousand times too fast for us. We had almost reached the city limits when we met a prominent Roman Catholic bishop, who stopped to enquire the cause of the intended execution. While the bishop was inquiring of the Confederate officer about us, Captain Flinn, who was a Catholic, said he was being executed without the "rites of clergy." The bishop, who was a great friend and admirer of Jefferson Davis, President of the Southern Confederacy, exclaimed, "that would never do," and he requested the Confederate officer to move slowly and he would hasten to see President Davis, and if possible get a delay for a short time. The cart moved on and the bishop hurried at a rapid pace to interview President Davis. The bishop was mounted on a full-blooded and a very spirited horse, and he seemed to us to go like the wind when he started for the residence of his friend. We moved on to a small hill on which was a single tree, and to this tree the cart took its way. When the tree was reached, ropes were placed around our necks, and we were doomed to be hanged. This would have been an ignominious death if we had been guilty of any crime punishable by death, but we had committed no crime, and yet we did not want to die in that way. We had a slight ray of hope in the bishop's intercession for us, but it was too slight to allay our fears for the worst. I was very weak. Mine Gott ! Jim, I had never felt so badly in all my life before. I was so weak that the tree and the guards seemed to be moving in a circle around me. We stood up in the cart, so when it moved away we would dangle between the earth and sky, and in this way our existence was to end. No courier from the bishop was in sight and mine Gott ! Jim, the suspense was terrible for us to bear. The Confederate officer took out his watch, and informed us that while his instructions were to have us executed before noon, he would wait until one minute of twelve, and then if there was no sign of a courier, the cart would be driven away and the arbitrary orders of the War Department of the Southern Confederacy, would be obeyed.

Half-past eleven arrived and yet no signs of any courier from the bishop. Mine Gott! Jim, our legs became so weak that we could not stand any longer, so we requested that we might be permitted to sit down in the cart until the time for us to be executed arrived. Then we would stand up and the ropes could be adjusted to our necks and the execution concluded. The ropes were then untied and we were permitted to sit down on the side of the cart. Ten minutes more passed in dead silence, and yet no eye could detect any signs of a courier. At the end of another ten minutes we stood up and the ropes were adjusted to our necks, and the Confederate officer was raising his sword as a sign to the driver to move away, when a cloud of dust was observed in the distance, and the Confederate officer hesitated for a few moments, when a horseman covered with dust, and his horse covered with foam, dashed up to the officer, and handed him a dispatch. He opened it quickly and read, Captains Sawyer and Flinn are reprieved for ten days.

Mine Gott ! Jim, I never felt so happy in my life; and Flinn and I embraced each other and cried like babies. The ropes were untied and the cart started slowly back for Libby Prison. We never learned the name of the officer who was detailed to execute us. Our comrades were greatly rejoiced to see us return alive, and made many inquiries concerning the postponement of the execution.

On our return we were taken to the headquarters of General Winder, where we were warned not to delude ourselves with any hope of escape, as retaliation must and would be inflicted, and it was added that the execution would positively take place on the 16th, ten days hence. We were then conducted back to Libby Prison, and taken to the second story to our old place on the floor. We were not permitted to remain there very long, when we were taken to the cellar and placed in a dungeon, and isolated from the world and our companions ; and the only company we now had were the rats and the vermin, which swarmed over us in great numbers.

After resting for a short time to compose my thoughts, I asked for writing material, which was furnished me with a candle, and then on an old board for a writing desk I wrote [a] letter to my wife, which I started on July 6th, but did not finish until the next day. ... The Confederate officer read it and then sent it through the lines under a flag of truce, with a lot of other mail from my fellow-officers.

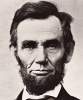

I calculated that it would require some four or five days for the letter to reach its destination, and then I knew that my wife would make superhuman efforts to save me, and this was the only bright ray of hope that lighted up that dark dungeon cell in which I was placed. The letter reached my wife on the 13th, and she was greatly shocked and almost overcome, and when she read it again and comprehended the full meaning of it she collapsed, but realizing that any delay might prove fatal to me she rallied, and as soon as she could make the necessary preparations she, in company with Captain Whilldin, started for Washington, where they arrived on the night of the 14th of July. After eating a lunch they proceeded to the White House, and secured an interview with President Lincoln, before ten o'clock. The President was greatly startled, as well as shocked and agitated by the recital of the way I, her husband, was treated in the Confederate prison at. Richmond, and after encouraging her to be brave he said, "Mrs. Sawyer, I do not know whether I can save your husband and Captain Flinn, from the gallows, but I will do all in my power to do so. They are two brave men and I will make extraordinary efforts to save them. If you and your friend will call before noon to-morrow, I will be pleased to inform you what action I have taken."