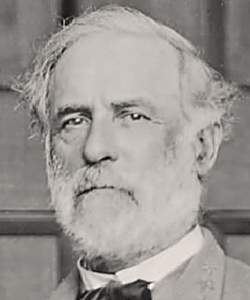

Robert E. Lee, Joining the Confederacy (American National Biography)

Scholarship

On 18 April [1861], following the bombardment of Fort Sumter on 12-14 April, Francis Preston Blair, Sr., on behalf of President Abraham Lincoln, directly asked Lee whether he would take command of an enlarged U.S. Army. But Lee reiterated what he had said to [General Winfield] Scott. On 20 April, having learned that Virginia had seceded two days earlier, Lee submitted his resignation. It was a painful decision but one that in its expression of loyalty to home and kindred has commanded sympathy even from those who cannot admire it.

On 21 April Governor John Letcher of Virginia dispatched a messenger offering Lee command of the military and naval forces of the state, with the rank of major general, but the messenger evidently passed Lee while the latter was en route from Arlington to Richmond in response to an earlier invitation from the governor. Lee accepted the commission from Letcher's hand on 22 April. On 10 May the Confederate War Department gave Lee command of its forces in Virginia, though it proceeded to send troops and other officers there apparently without regard to him. Following the voters' ratification of the Virginia Ordinance of Secession on 23 May, the state turned over its forces to the Confederacy on 8 June, while Lee had already been commissioned brigadier general in the Confederate regular army on 14 May.

On 21 April Governor John Letcher of Virginia dispatched a messenger offering Lee command of the military and naval forces of the state, with the rank of major general, but the messenger evidently passed Lee while the latter was en route from Arlington to Richmond in response to an earlier invitation from the governor. Lee accepted the commission from Letcher's hand on 22 April. On 10 May the Confederate War Department gave Lee command of its forces in Virginia, though it proceeded to send troops and other officers there apparently without regard to him. Following the voters' ratification of the Virginia Ordinance of Secession on 23 May, the state turned over its forces to the Confederacy on 8 June, while Lee had already been commissioned brigadier general in the Confederate regular army on 14 May.

Russell F. Weigley, "Lee, Robert E.," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/04/04-00622.html.

Robert E. Lee, Confederate Offensive in 1862 (American National Biography)

Scholarship

In March [1862], [General George] McClellan had moved his main force by sea from Washington to Fort Monroe; then he began an advance toward the Confederate capital by way of the peninsula between the York and James rivers. On 31 May, General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding the Confederate forces opposing him, was wounded at the battle of Fair Oaks or Seven Pines. The next day Lee succeeded to Johnston's command, which he promptly designated the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee applied his principles of concentrating force and seizing the initiative. He had Jackson join him with the Valley Army, and, thus reinforced, he conducted a series of attacks against McClellan just outside Richmond in the Seven Days battles of 25 June-1 July.

The battles saved Richmond and transformed Lee from an apparent failure to the hero of the Confederacy. Lee himself was nevertheless disappointed with the Seven Days, because he had hoped to destroy the Army of the Potomac...He progressed in his strategic convictions beyond the belief that the Confederacy must seize the initiative to conclude also that the initiative must be pushed to a decisive, war-ending victory. Otherwise the superior resources of the Union would enable it to outlast local or regional setbacks. The Confederacy must compel the North to recognize its independence rapidly or it would not be able to do so at all.

The battles saved Richmond and transformed Lee from an apparent failure to the hero of the Confederacy. Lee himself was nevertheless disappointed with the Seven Days, because he had hoped to destroy the Army of the Potomac...He progressed in his strategic convictions beyond the belief that the Confederacy must seize the initiative to conclude also that the initiative must be pushed to a decisive, war-ending victory. Otherwise the superior resources of the Union would enable it to outlast local or regional setbacks. The Confederacy must compel the North to recognize its independence rapidly or it would not be able to do so at all.

Russell F. Weigley, "Lee, Robert E.," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/04/04-00622.html.

Robert E. Lee, Battle of Gettysburg (American National Biography)

Scholarship

Following Chancellorsville, Davis finally reinforced Lee to the strength the general believed necessary for a new invasion of the North. On 3 June 1863 Lee set out for Pennsylvania, but he did so without Stonewall Jackson, who had died on 10 May of complications from wounds suffered at Chancellorsville. Ever since the Pennsylvania campaign climaxed at Gettysburg on 1-3 July, debate has persisted over whether Jackson's absence accounts for Lee's inability--at Gettysburg or in any of his subsequent battles--to achieve the sort of complete tactical success that the flanking maneuvers led by Jackson at Second Manassas and Chancellorsville had provided. Probably the circumstances of the battle of Gettysburg would have precluded such bold maneuver anyway; in particular, Lee was hampered by a lack of familiarity with the terrain. At Gettysburg less ambitious attempts against both enemy flanks failed on 2 July, and the next day the battle ended with the defeat of Major General George E. Pickett's famous charge against the Union center. The skillful defensive tactics of Major General George G. Meade as Federal commander helped impose on Lee his highest casualties yet: 28,000, about 35 percent.

Lee probably gambled on Pickett's Charge because he recognized that no more throws of the dice of a strategic offensive would be possible. His cumulative casualties were already too great: here lay the fatal flaw in his strategy. He would still, nevertheless, risk attacking on the battlefield in the hope of destroying the enemy army, as he had done from the beginning.

Lee probably gambled on Pickett's Charge because he recognized that no more throws of the dice of a strategic offensive would be possible. His cumulative casualties were already too great: here lay the fatal flaw in his strategy. He would still, nevertheless, risk attacking on the battlefield in the hope of destroying the enemy army, as he had done from the beginning.

Russell F. Weigley, "Lee, Robert E.," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/04/04-00622.html.

Robert Edward Lee (Appleton's)

Reference

On 20 April, 1861, three days after the Virginia convention adopted an ordinance of secession, he resigned his commission, in obedience to his conscientious conviction that he was bound by the act of his state. His only authenticated expression of opinion and sentiment on the subject of secession is found in the following passage from a letter written at the time of his resignation to his sister, the wife of an officer in the National army: “We are now in a state of war which will yield to nothing. The whole south is in a state of revolution, into which Virginia, after a long struggle, has been drawn; and though I recognize no necessity for this state of things, and would have forborne and pleaded to the end for redress of grievances, real or supposed, yet in my own person I had to meet the question whether I should take part against my native state. With all my devotion to the Union, and the feeling of loyalty and duty of an American citizen, I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relatives, my children, my home. I have therefore resigned my commission in the army, and, save in defence of my native state – with the sincere hope that my poor service may never be needed – I hope I may never be called upon to draw my sword.”

James Grant Wilson and John Fiske, eds., "Lee, Robert Edward," Appleton’s Cyclopaedia of American Biography (New York: Appleton & Co., 1887), 3: 668.

Robert Edward Lee (Jones, 2002)

Reference

The political crisis was also a personal dilemma for Lee. Although he opposed both secession and slavery (believing slavery harmed whites more than blacks) and loved the Union, Lee was loyal to Virginia above all else. Scott offered him command of the Union armies, but Lee refused the day after Virginia seceded and resigned his commission on April 20, 1861. Governor John Letcher quickly appointed him major general in command of state troops, two days before Lee’s resignation was accepted by the U.S. Army on April 25.

Terry Jones, Historical Dictionary of the Civil War, vol. 1 (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2002), 807.

Robert Edward Lee, Antebellum Military Career (National Cyclopedia)

Reference

When the war with Mexico began Capt. Lee was made chief engineer of the U.S. army, and was placed on the personal staff of Gen. Scott, who sought his advice constantly, and ascribed the fall of Vera Cruz to his strategic ability. Lee was thrice brevetted, the last time as colonel, for gallantry at Chapultepec, where he was wounded. Peace declared, he had charge of the construction of works for the defense of the harbor of Baltimore, and then, 1852-55, was superintendent of the academy, West Point, broadening its curriculum and giving it rank with the best military schools of Europe. In 1855 he was appointed lieutenant-colonel of the 2d regiment of cavalry, and until February, 1861, was stationed at Fort Cooper, Texas. While at Arlington, on a furlough, in 1859, John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry occurred, and Lee, at the head of a company of U.S. marines, captured Brown and his few remaining followers. In January, 1861, he learned that civil war was impending, and in a letter to his wife said: “I can do nothing to hasten or retard it.” In February he was called to Washington and soon after was offered command of the active army of the United States; but, though deprecating secession and war, he refused to have any part in an invasion of the South.

"Lee, Rober Edward," National Cyclopaedia of American Biography (New York: James T. White & Company, 1897), 4: 96.

Robert Edward Lee, Defending Virginia and the Confederacy (National Cyclopedia)

Reference

Virginia passed an ordinance of secession on April 17th, and finding that he must soon be ordered on duty or be compelled to resign under orders, Lee, on the 20th, after a severe mental struggle, tendered his resignation to Gen. Scott. On the same day he announced his decision to members of his family, assuring them he had no other ambition than to remain at home, and that, save in the defense of his native state, he had no desire ever again to draw his sword. Three days later, on invitation of Gov. Letcher, he appeared before the Virginia convention in session at Richmond, having been nominated by the executive major-general and commander-in-chief of the forces of the state. The prestige of his deeds, and of those of his ancestors, the nobility of his character, his importance as a leader, shown by the efforts to keep him in the U.S. army, all had weight, and he was appointed by acclamation. Assuming command April 23d, he held it until June 8th, when, under an agreement between Virginia and the Confederate government, he turned it over to the latter. In May he was given the additional task of commanding all troops of the Confederate States as soon as they arrived in Virginia.

"Lee, Rober Edward," National Cyclopaedia of American Biography (New York: James T. White & Company, 1897), 4: 96.

Robert Edward Lee, Postbellum (National Cyclopedia)

Reference

He considered that his own life, so far as it related to public affairs, had ended in 1865, and that the exposition of the war and of his own part in it, must be left to history. But, although silent, he was conscious that from the hour when he assumed command of the army of northern Virginia up to the moment when he laid it down, he could not fairly be said to have lost a single battle. H declined offers to become president of corporations and business associations and of several institutions of learning, but finally accepted the presidency of Washington College, Lexington, Va. (now Washington and Lee University), and was inaugurated Oct. 2, 1865. He brought the college from a condition of almost hopeless ruin to one of great prosperity, and impressed his own nobility of character upon every detail of its life and thought.

"Lee, Rober Edward," National Cyclopaedia of American Biography (New York: James T. White & Company, 1897), 4: 100.

Robert Edward Lee (New York Times)

Obituary

Gen. Robert E. Lee.

Intelligence was received last evening of the death at Lexington, Va., of Gen. ROBERT E. LEE, the most famous of the officers whose celebrity was gained in the service of the Southern Confederacy during the late terrible rebellion. A report was received some days ago that he had been smitten with paralysis, but this was denied, and thought it was admitted that he was seriously ill, hopes of his speedy recovery seem to have been entertained by his friends. Within the last two or three days his symptoms had taken an unfavorable turn, and he expired at 9 1/2 o’clock yesterday morning of congestion of the brain, at the age of sixty-three years, eight months and twenty three days.

ROBERT EDMUND LEE was the son of Gen. HENRY LEE, the friend of WASHINGTON, and a representative of one of the wealthiest and most respected families of Virginia. Born in January, 1807, he grew up amid all the advantages which wealth and family position could give in a republican land, and received the best education afforded by the institutions of his native State. Having inherited a taste for military studies, and an ambition for military achievements, he entered the National Academy at West Point in 1825, and graduated in 1829, the second in scholarship in his class. He was at once commissioned Second Lioutenant of engineers, and in 1835 acted as assistant astronomer in drawing the boundary line between the States of Michigan and Ohio. In the following year he was promoted to the grade of First Lieutenant, and in 1838 received a Captain’s commission. On the breaking out of the war with Mexico he was made Chief-Engineer of the army under the command of Gen. Wool. After the battle of Cerro Gordo, in April, 1847, in which he distinguished himself by his gallant conduct, he was immediately promoted to the rank of Major. He displayed equal skill and bravery at Contreras, Cherubusco and Chapultepec, and in the battle at the last-mentioned place received a severe wound. His admirable conduct throughout his struggle was rewarded before its close with the commission of a Lieutenant-Colonel and the brevet title of Colonel. In 1852 he was appointed to the responsible position of Superintendent of the Military Academy at West Point, which he retained until 1855. On retiring from the charge of this institution he was made Lieutenant-Colonel of the Second Cavalry, and on the 16th of March, 1861, received the commission of Colonel of the First Cavalry.

Thus far the career of Col. LEE had been one of honor and the highest promise. In every service which had been intrusted to his hands he had proved efficient, prompt and fathful, and his merits had always been readily acknowledged and rewarded by promotion. He was regarded by his superior officers as one of the most brilliant and promising men in the army of the United States. His personal integrity was well known, and his loyalty and patriotism was not doubted. Indeed, it was in view of the menaces of treason and the dangers which threatened the Union that he had received his last promotion, but he seems to have been thoroughly imbued with that pernicious doctrine that his first and highest allegiance was due to the State of his birth. When Virginia joined the ill-fated movement of secession from the Union, he immediately threw up his commission in the Federal Army and offered his sword to the newly-formed Confederacy. He took this step, protesting his own attachment to the Union, but declaring that his sense of duty would never permit him to “raise his hand against his relatives, his children, and his home.” In his farewell letter to Gen. SCOTT, he spoke of the struggle which his step had cost him, and his wide declared that he “wept tears of blood over this terrible war.” There are probably few who doubt the sincerity of his protection, but thousands have regretted, and his best friends will ever have to regret the error of judgment, the false conception of the allegiance due to his Government and his country, which led one so rarely gifted to cast his lot with traitors, and devote his splendid talents to the execution of a wicked plot to tear asunder and ruin the Republic in whose service his life had hitherto been spent.

He resigned his commission on the 25th of April, 1861, and immediately betook himself to Richmond, where he was received with open arms and put in command of all the forces of Virginia by Gov. LETCHER. On the 10th of May he received the commission of a Major-General in the army of the Confederate States, retaining the command in Virginia, and was soon after promoted to the rank of General in the regular army. He first took the field in the mountainous region of Western Virginia, where he met with many difficulties, and was defeated at Greenbrier by Gen. J. J. REYNOLDS on the 3d of October, 1861. He subsequently sent to take command of the Department of the South Atlantic Coast, but after the disabling of Gen. JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON at the battle of Fair Oaks, in the Spring of 1862, he was recalled to Virginia, and placed at the head of the forces defending the capital, which he led through the remainder of the campaign of the Chickahominy. He engaged with the Army of the Potomac under his old companion-in-arms, Gen. MCCLELLAN, and drove it back to the Rappahannock. He afterward, in August, 1862, attacked the Army of Virginia under Gen. POPE, and, after driving it back to Washington, crossed the Potomac into Maryland, where he issued a proclamation calling upon the inhabitants to enlist under his triumphant banners. Meantime MCCLELLAN gathered a new army from the broken remnants of his former forces, and met LEE at Hagerstown, and, after a battle if two days, compelled him to retreat. Reinforced by “Stonewall” JACKSON, on the 16th of September, he turned to renew the battle, but after two days of terrible fighting at Sharpsburg and Antietam, was driven from the soil of Maryland. Retiring beyond the Rappahannock, he took up his position at Fredericksburg, where he was attacked, on the 13th of December, by Gen. BURNSIDE, whom he drove back with terrible slaughter. He met with the same success in May, 1863, when attacked by HOOKER, at Chancellorsville. Encouraged by these victories, in the ensuing Summer he determined to make a bold invasion into the territory of the North. He met Gen. MEADE at Gettysburg, Penn., on the 1st of July, 1863, and after one of the most terrible and destructive battles of modern times, was driven from Northern soil. Soon after this, a new character appeared on the battle-fields of Virginia, and Gen. LEE found it expedient to gather his forces for the defense of the Confederate capital against the determined onslaughts of Gen. GRANT. In the Spring and Summer of 1864 that indomitable soldier gradually inclosed the City of Richmond as with a girdle of iron, which he drew closer and closer with irresistible energy and inexorable determination, repulsing the rebel forces whenever they ventured to make an attack, which they did several times with considerable vigor. In this difficult position, holding the citadel of the Confederacy, and charged with its hopes and destinies, LEE was made Commander-in-Chief of the armies of the South. He held out until the Spring of 1865, vainly endeavoring to gather the broken forces of the Confederacy, and break asunder the terrible line which was closing around them. After a desperate and final effort at Burkesville, on the 9th of April, 1865, he was compelled to acknowledge his defeat, and surrendered his sword to Gen. GRANT on the generous terms that were dictated by that great soldier. Lee retired under his parole to Weldon, and soon after made a formal submission to the Federal Government, Subsequently, by an official clemency, which is probably without a parallel in the history of the world, he was formally pardoned for the active and effective part he had taken in the mad effort of the Southern States to break up the Union and destroy the Government. Not long after his surrender he was invited to become the President of Washington University, at Lexington, Va., and was I installed in that position on the 2d of October, 1865. Since that time he has devoted himself to the interests of that institution, keeping so far as possible aloof from public notice, and by his unobtrusive modesty and purity of life, has won the respect of even those who most bitterly deplore and reprobate his course in the rebellion.

"Obituary," New York Times, October 13, 1870, p. 4-5.