William Gannaway Brownlow (Congressional Biographical Directory)

Reference

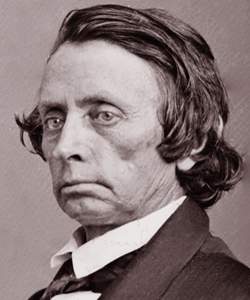

BROWNLOW, William Gannaway, (uncle of Walter Preston Brownlow), a Senator from Tennessee; born near Wytheville, Wythe County, Va., August 29, 1805; attended the common schools; entered the Methodist ministry in 1826; moved to Elizabethton, Tenn., in 1828 and continued his ministerial duties; published and edited a newspaper called the Whig at Elizabethton in 1839; moved the paper to Jonesboro, Tenn., in 1840 and to Knoxville, Tenn., in 1849, and from his caustic and trenchant editorials became widely known as ‘the fighting parson’; unsuccessful candidate for election in 1842 to Congress; appointed by President Millard Fillmore in 1850 a member of the Tennessee River Commission for the Improvement of Navigation; delegate to the constitutional convention which reorganized the State government of Tennessee in 1864; elected Governor in 1865 and again in 1867; elected as a Republican to the United States Senate and served from March 4, 1869, to March 3, 1875; was not a candidate for reelection; chairman, Committee on Revolutionary Claims (Forty-third Congress); returned to journalism in Knoxville, Tenn., until his death there on April 29, 1877; interment in the Old Grey Cemetery.

“Brownlow, William Gannaway,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774 to Present, http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=B000963.

William Gannaway Brownlow, Whig & Know Nothing (American National Biography)

Scholarship

Brownlow…also became a champion of the new Whig party, which organized in the 1830s in opposition to Andrew Jackson and the Democratic party. In 1839 Brownlow established his first newspaper, the Tennessee Whig, to defend both religious and political truth. Published with the motto "Cry Aloud and Spare Not," the paper soon became one of Tennessee's leading Whig organs while sustaining its editor's reputation as a reckless incendiary. He relocated the paper to nearby Jonesborough (later Jonesboro) in 1840 before finally settling in 1849 in Knoxville, which became his permanent home.

Brownlow's Whiggery expressed itself most clearly in his advocacy of Henry Clay's presidential prospects. His son later recalled that the only time he saw his father weep was after he learned of Clay's defeat in the presidential election of 1844. When in 1848 the Whig National Convention bypassed Clay, Brownlow refused to support the party nominee Zachary Taylor. His recalcitrance continued into the 1852 election when he promoted Daniel Webster instead of Winfield Scott, whom the Whigs nominated in place of Millard Fillmore, the president who had signed into law the national compromise over slavery's expansion that Clay had proposed in 1850. After the demise of the national Whig party, Brownlow became one of the leading Southern advocates of the nativist Know Nothing movement.

Brownlow's Whiggery expressed itself most clearly in his advocacy of Henry Clay's presidential prospects. His son later recalled that the only time he saw his father weep was after he learned of Clay's defeat in the presidential election of 1844. When in 1848 the Whig National Convention bypassed Clay, Brownlow refused to support the party nominee Zachary Taylor. His recalcitrance continued into the 1852 election when he promoted Daniel Webster instead of Winfield Scott, whom the Whigs nominated in place of Millard Fillmore, the president who had signed into law the national compromise over slavery's expansion that Clay had proposed in 1850. After the demise of the national Whig party, Brownlow became one of the leading Southern advocates of the nativist Know Nothing movement.

Jonathan M. Atkins, "Brownlow, William Gannaway," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/04/04-00165.html.

William Gannaway Brownlow, Secession & Civil War (American National Biography)

Scholarship

As the question of slavery's expansion became the nation's most pressing issue, [Brownlow] championed the preservation of both slavery and the Union. A slaveowner himself, he defended slavery on biblical grounds, but at the same time he condemned advocates of secession as radical fanatics who sought to dissolve the Union merely for personal gain. With the onset of the Civil War, Brownlow, despite his devotion to slavery, chose to remain loyal to the Union. Ultimately, he accepted emancipation as a means to help to defeat the Confederacy, though he also advocated removing the freed slaves to a territory away from the white population.

Despite Tennessee's withdrawal from the Union, Brownlow continued to publish his paper and condemn the Confederacy until he was arrested and briefly imprisoned in late 1861. Released on condition that he leave the state, he in March 1862 began a speaking tour of several northern cities. This tour earned him a small fortune while making him a national symbol of Southern loyalty to the Union. On a break from this tour, Brownlow stayed at Crosswicks, New Jersey, and composed Sketches of the Rise, Progress, and Decline of Secession (1862). Better known as Parson Brownlow's Book, this publication brought him greater renown by popularizing even further his acrimonious denunciation of Confederate leaders. He returned to East Tennessee as an agent for the U.S. Treasury following the region's occupation by Federal troops in December 1863. After he had also revived his paper, he took a leading role in the movement to reestablish civil government in Tennessee in 1865.

Despite Tennessee's withdrawal from the Union, Brownlow continued to publish his paper and condemn the Confederacy until he was arrested and briefly imprisoned in late 1861. Released on condition that he leave the state, he in March 1862 began a speaking tour of several northern cities. This tour earned him a small fortune while making him a national symbol of Southern loyalty to the Union. On a break from this tour, Brownlow stayed at Crosswicks, New Jersey, and composed Sketches of the Rise, Progress, and Decline of Secession (1862). Better known as Parson Brownlow's Book, this publication brought him greater renown by popularizing even further his acrimonious denunciation of Confederate leaders. He returned to East Tennessee as an agent for the U.S. Treasury following the region's occupation by Federal troops in December 1863. After he had also revived his paper, he took a leading role in the movement to reestablish civil government in Tennessee in 1865.

Jonathan M. Atkins, "Brownlow, William Gannaway," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/04/04-00165.html.