Roger Taney (Dickinson Chronicles)

While at Dickinson, Taney came under the tutelage of Dr. Charles Nisbet, arguably one of the greatest educators of his day. If the correspondence between Nisbet and Taney’s father throughout 1792-1795 are any indication, the Principal became almost a surrogate father to the young and talented student. Taney was a leading member of the Belles Lettres Society and graduated as valedictorian of the twenty-four students in the class of 1795. This honor he always valued since the students themselves at the time were responsible for such selection.

Taney studied law under Judge Jeremiah Townley Chase in Annapolis before being admitted to the Maryland bar on June 19, 1799. After a brief time as a Federalist state representative, he began his legal career in earnest in Frederick, Maryland. There he also met and married Anne Phoebe Charlton Key, the sister of Francis Scott Key, in January, 1806. The couple would have six daughters.

Taney was elected to the Maryland State Senate in 1816 and came to dominate the state's Federalists. By 1820 he had also established himself as one of the leading attorneys in Maryland and in September, 1827 accepted the position of State Attorney General. As the Federalist Party faded away, Taney looked for other political outlets. He had always been an avid supporter and admirer of General Andrew Jackson, acting as chairman of the Jackson Central Committee of Maryland in the 1828 election. His longtime support was recognized in 1831 when President Jackson appointed him to the first of what were to be several posts in his cabinet. He initially served as both Attorney-General and acting Secretary of War. In a cabinet shuffle in 1833, Jackson appointed Taney as Secretary of the Treasury. The national controversy over the role of the Bank of the United States dictated that this was a highly sensitive post, but one for which Taney’s long experience in banking law qualified him well. Taney would serve from September 23, 1833 until his Senate confirmation was rejected and he resigned on June 24, 1834. Jackson then sought to have him appointed to the Supreme Court as an associate justice but this nomination was also blocked in the Senate. Jackson persisted, however, and on December 28, 1835, he nominated Taney to fill the vacancy on the Court left by the death of the legendary Chief Justice John Marshall. This time, despite the usual Whig opposition, he was confirmed and he took the oath of office on March 28, 1836.

Taney’s actions in his first decades largely calmed initial Whig fears that his appointment would politicize the Court and he settled into a careful career marked by strict construction of, not only the Constitution where it supported state sovereignty, but also of contract, as in Charles River Bridge vs. Warren Bridge. However, one case in particular has been the hallmark of Taney's tenure as Chief Justice. In 1856, a seemingly unnecessary supporting case for the 1820 Missouri Compromise, Dred Scott vs Sandford, was allowed before the Court. Taney wrote the majority opinion in the Scott case, confirming slaves as property by ruling against Negro citizenship and then declaring that the Compromise itself was unconstitutional because Congress had no right, under the constitutional protection of private property, to bar slavery from new territories.

As a child of Southern gentry, Taney immediately came under extreme Republican attack for this decision. He was personally opposed to slavery, having freed his own slaves, but his southern sensibilities and his own intimate knowledge of the institution led to his belief in the common southern anti-slavery solution of repatriation, as opposed to abolition. The case dogged the rest of his nine years as Chief Justice, even though he displayed a certain judicial brilliance in his later decisions with long and thoughtful opinions on the role of the states and national government in fugitive slave cases, in Ableman v. Booth just before the Civil War, and on the rights of civilians in wartime in Ex Parte Merryman during the conflict itself.

Plagued all of his life with ill health and never a rich man, Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney died on October 12, 1864, unmourned by most Northern supporters of a war against rebellion he believed privately the Union had no legal right to wage. He was 87 years old.

Roger Taney (American National Biography)

Roger Taney (White, 1988)

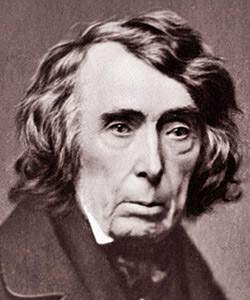

In a surviving portrait of Roger Taney his disheveled hair and pained, meditative expression create an ascetic appearance more appropriate to a saint than to the man who has come to be called the judicial defender of racism and human bondage. His reputation has been resurrected several times by scholars, who have pointed out that he was a judge of considerable talent and stature and that his association with the infamous Dred Scott decision needs to be viewed in the context of his other accomplishments. Yet he remains a symbol of the moral nadir of the American judicial tradition, when the Supreme Court of the United States publicly declared the “degraded status” of blacks in America and the inherent inferiority of their race, and gave legal sanction to the enslavement of blacks by whites. With Dred Scott to remind us of the ignorance and viciousness long embedded in American culture, Taney’s reputation may never be completely vindicated. He forces us to see the extent to which our institutions of government and our system of laws can become, even while administered by the educated and well-intentioned, affronts against humanity.

Taney was representative of educated professional Americans of his generation. Confronted with a rapidly expanding economy, changing political alignments, and the growth of cultural schizophrenia of which the system of black slavery was a root cause, he sought to adjust the nation’s institutions so that they might survive in the new conditions created by these phenomena. Like many other statesmen of his day, Taney tried and failed to solve the slavery problem, but his response to the problem, no more unsuccessful than any other response, has become particularly offensive with time. The tension between the humanitarian and egalitarian ideals associated with the founding of the American nation and the presence of black slavery was simply too debilitating and pervasive to admit of peaceful consensual solutions; moreover, it occurred at a time when consensual values were noticeably lacking throughout American civilization. The internal conflicts, of which the slavery issue was the most dramatic example, were never truly resolved, but engendered a forced reconciliation of the nation, with one set of attitudes summarily superimposed on another. Taney can hardly be faulted for failing to provide a set of fundamental constitutional principles by which the question of slavery could be amicably settled. Indeed, given the ideological context of his time, none existed. But he can, from another perspective, be faulted for the political and moral choices he made in attempting to settle the question.

Between 1836, the year when Taney replaced Marshall as Chief Justice, and 1857, the year of the Dred Scott decision, an affirmative justification for racially based enslavement was developed and refined in America. On the Court, Taney provided legal support for that justification. His intention was benign; he was concerned not with preserving slavery as such but with maintaining peaceful co-existence between competing ideologies in the nation. One cannot, however, ignore the fact that, despite his motives, Taney attempted to use the power of the judicial branch of government to further the existence of a subculture in which persons of one race were considered the property of persons of another. In this use of his office Taney demonstrated the moral and political limits of judicial power in America.

Roger Taney (Great Southerners)

Taney was born in Maryland, and was a brother- in-law of Francis Scott Key, author of the national song, “The Star-Spangled Banner.” His acuteness and eloquence soon placed him amoung the foremost lawyers of his State. He had political ambitions, but became somewhat unpopular on account of defending Gen. James Wilkinson before a court-martial. Gen. Wilkinson, who had been a soldier under Washington, becoming intimate with Benedict Arnold and Aaron Burr during the time, had undertaken the betrayal of his country to Spain by trying to induce the pioneers of Kentucky and the western territory of North Carolina to become alienated from the colonies and attach themselves to Spain. Later on, he was thought to be connected with Burr in his scheme to erect a southwestern empire. Through an idea that Gen. Wilkinson was unjustly charged, Taney was induced to defend the officer, sharing the odium that attached to the latter, and refusing to take a fee. Eight years afterwards, he again defied the disapprobation of his neighbors by courageously appearing in defense of Jacob Gruber, a Methodist minister from Pennsylvania who had in a camp meeting condemned slavery in bitter language, and who was indicted as an inciter of insurrection among the negroes. In view of an expression afterwards used by Taney in the famous Dred Scott decision, it is interesting to note that in his opening argument for Gruber he declared of slavery that “while it continues it is a blot on our national character.”

Taney was a great friend of Andrew Jackson, becoming the latter’s most trusted counselor, and encouraged the President in his war on the United States Bank. This made him unpopular with Jackson’s political enemies, and when he was appointed Secretary of State the hostile majority rejected the appointment, it being the first time that the President’s selection of a cabinet officer had not been confirmed.

After the death of John Marshall, Taney was nominated to be Chief Justice of the United States, and though Henry Clay was active in denouncing the appointment, it was confirmed by a vote of twenty-nine against fifteen. Two of America’s greatest law writers (Joseph Story and Jame Kent) were on the bench with him, and often dissented from his opinions. The truth is, Taney believed in State rights, while Marshall was inclined against the doctrine, and that fact is one of the reasons the latter has always been more popular with the North, and not because he was a great jurist.

From 1854 till his death Judge Taney was called upon to decide cases that affected not only individuals, but sections of the Union. In that year, in the midst of the excitement that attended the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska bill and strife of the slaveholders and free-soilers, he was confronted by the famous Dred Scott case. It involved the question: Could Congress exclude slavery in the Territories? After being twice argued, the case was decided in 1857. The opinion of the court was written by the Chief Justice. He held that Dred Scott, a slave, was debarred from seeking a remedy in the United States Court of Missouri, as he was not a citizen of that State, and, being a slave, could not become a citizen by act of any State or of the United States. In the opinion this dictum was made, which set the abolitionists to harping more than ever: “They [the negroes] had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect, and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.” As a consequence, the decision - containing a proposition that we must look on to-day as an extreme one – produced a strong reaction in favor of the antislavery party. William H. Seward, in the Senate, made a direct attack on the Supreme Court.

In 1858 a second “slave case” was presented and as all these assisted materially in hastening the civil war, it is necessarily of interest as history as well as a pointer to a great man’s way of reasoning. Sherman M. Booth, who had been sentenced by the United States District Court for aiding in the escape of a negro from slavery, was released by the Supreme Court of Wisconsin, which refused to notice the subsequent mandates of the Supreme Court of the United States relative to the affair.

This was bordering on the doctrine of nullification, which appeared odious in South Carolina a quarter of a century before. The Supreme Court of the United States reversed the judgment of the Court of Wisconsin, declaring the fugitive slave law constitutional – that it was the law of the land; whereupon Wisconsin’s Legislature placed that State side by side with South Carolina as to nullification. It declared that the States, as parties to a compact, have an equal right to determine infractions of their rights and the mode of their redress, and that the judgment of the Federal Court was “void and of no force.”

Chief Justice Taney died on the day on which Maryland abolished slavery.

Roger Taney (New York Times)

Judge TANEY was a man of pure moral character, and of great legal learning and acumen. Had it not been for his unfortunate Dred Scott decision, all would admit that he had, through all those years, nobly sustained his high office. That decision itself, wrong as it was, did not spring from a corrupt or malignant heart. It came, we have the charity to believe, from a sincere desire to compose, rather than exacerbate, sectional discord. But yet it was none the less an act of supreme folly, and its shadow will ever rest on his memory.

The original mistake was in gratuitously attempting to settle great party questions by judicial decision. The attempt was gratuitous, for the very decision of Judge TANEY, that the court had no jurisdiction in the case over the court below, was in itself sufficient reason for not undertaking a decision of all the constitutional questions incidentally connected with its merits. What Justice CURTIS declared in his very able option, that “on so grave a subject as this, such an exertion of judicial power transcends the limits of the authority of the court, as described by its repeated decisions,” will unquestionably be the judgment of history.

The Supreme Court never from its first organization took faith which so much impaired the public action in its impartiality and wisdom. In view of the sides taken by the respective Judges, it was impossible for the body of the people not to believe that the court was influenced by party and sectional feeling. The court should have foreseen this invidious position, and have avoided it, by taking no further cognizance of the case than necessity absolutely demanded. It was useless for them to attempt to settle great political questions. Such attempts before made, even in the palmist days of the court, and on questions of immeasurably less importance, had failed. The court is no oracle. It does not pronounce its decisions with a categorical Yea or Nay. It must, like a legislative body, stand on its rendered reasons; and these reasons must stand the test of criticism before they can be accepted as conclusive, and as authoritative law. If the reasoning of the court is no more cogent and luminous than the reasoning of the legislature, it is worth no more. No candid man who has read the decision of Judge TANEY will say that that opinion evinced more ability, more clearness of perception and strength of reasoning than had been displayed by Mr. WEBSTER and Mr. CLAY in the Senate, in their maintenance of opposite opinions. Nor will any candid man who has read the dissenting opinions of Judges CURTIS and MCLEAN claim that their views were not as cogently put as those of the Chief Justice. It was a natural necessity that the final solution of these great civil questions could come only from continued public discussion, and the condition in which the public mind eventually reposes.

The Dred Scott decision was made public the very month that President BUCHANAN acceded to power, and it formed the basis of his whole policy in respect to Slavery through his entire administration. It shipwrecked both him and his party. It contributed, more than all other things combined, to the election of President LINCOLN. The people would not abide this attempt of the majority of the Supreme Court to foist upon the Constitution the extremist dogmas of JOHN C. CALHOUN. They would not tolerate the doctrine that the Constitution, by its own force, established Slavery in all the Territories of the United States, making Slavery a national instead of a local institution. That the Dred Scott decision was a complete yielding to the full desires and demands of Slavery, is made strikingly manifest by the fact that the Montgomery Constitution, which was shaped by slaveholders without the slightest let or hindrance, does not contain a syllable in the interest of Slavery which is not found precisely in this Dred Scott Decision or Chief-Justice TANEY. There is no shadow of a new guaranty for this institution except the section that in all newly acquired territory “Slavery shall be recognized and protected by Congress and by the territorial government, and the inhabitants of the several States shall have the right to take such territory any slaves lawfully held by them;” and another section securing the right of “transit and sojourn in any State with slaves and other property.” Those are just the points on which would have been secured for Slavery under the Federal Constitution, had Judge TANEY’S interpretation become established law.

His removal by death will make an epoch in the history of the Supreme Court. Unquestionably his place will be filled by some jurist who is in perfect accord with all the great Union principles and Anti-Slavery sentiments which will henceforth control the executive and legislative branches of the Government. It is true that the old Democratic Judges WAYNE, CATRON, NELSON, GRIER, and CLIFFORD will still constitute half of the court; but even were they disposed to make another political decision in the interest of Slavery, their combined opinions would have no effect against the other half other court, headed by the Chief-Justice. Whatever great questions may be forced upon the court in connection with the rehabilitation of the States whose people have been in rebellion we may now be confident, will be adjudicated in accordance with the fundamental principles of our Government, as recognized by its founders, and in harmony, too, with the great policies imposed upon the country by the necessity of destroying the present rebellion and every possibility of its recurrence in the future.

Roger Taney (The Library of Historical Characters and Events)

ALREADY fifty-nine years of age when he was made Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, Roger B. Taney wielded the extensive power of his position for twenty-eight years, and during that time had great influence on the tendency of its decisions. Far from extending or exalting the power of the Federal Union as Marshall had done, he sought to protect the States in the full exercise of their reserved powers. Yet he did much to guide and regulate the wonderful material improvement of the country, due to the new applications of steam and various inventions.

Roger Brooke Taney was born on March 17, 1777, in Calvert county, Maryland. He was descended from an English Roman Catholic family, who were among the settlers of Maryland. In the faith which he had inherited he remained constant to the end. He graduated from Dickinson College in 1795, studied law at Annapolis and was admitted to the bar in 1799. He was also then elected to the State legislature from his native county as a Federalist, but when he removed to Frederick in 1801, he was defeated. His extensive and lucrative law practice carried him into courts of every kind, even into a court martial. In 1806 he married Anne Phebe Charlton Key, a sister of Francis Scott Key, the author of "The Star-Spangled Banner." Taney was a member of the State Senate from 1816 to 1821. In 1819 he defended Jacob Gruber, a Pennsylvania Methodist preacher, who had been indicted for preaching at a camp-meeting against slavery and thus inciting slaves to insurrection. In this trial Taney called slavery "a blot on our national character" and "a subject of national concern which may at all times be freely discussed." Taney removed to Baltimore in 1823 and soon became the acknowledged leader of the State bar. In 1827 he was appointed Attorney General of Maryland, although his political views as a Democrat were opposed to those of the Governor. In June 1831 he was appointed by President Jackson Attorney General of the United States, and became the President's most trusted adviser.

The Bank of the United States had been re-established at Philadelphia in April, 1816, with a charter for twenty years. It had nineteen branches, which were afterwards increased to twenty-five. Nicholas Biddle became its president in January, 1823. It was charged with having used its influence against Jackson in his first term. Professor W. G. Sumner says, "The public deposits were banging about the money-market like a cannon-ball loose in a ship's hold." Taney, who dreaded a moneyed aristocracy, abhorred all alliance between the Government and the money-power as fatal to liberty and high civilization. When the question of renewing the Bank's charter came up in 1832, Taney wrote to Jackson, advising against it. He believed it had violated its charter and was corrupting the country. When Congress passed a bill for its renewal in July, Jackson vetoed it. Taney was the only member of the Cabinet that approved the message. A year later he went further and suggested the removal of the Government deposits. The President decided on this course, but Duane, then Secretary of the Treasury, declined to plunge the fiscal concerns of the country into confusion at a time when they were conducted by the legitimate agent with safety and regularity. He was then removed from office and Taney put in his place in September, 1833. His order was issued at once that after October 1st the revenues should be deposited in certain State banks. The deposits already in the United States Bank (about $9,000,000) were to be drawn out when needed for the use of the Government. A panic and general distress followed, which the friends of the Bank attributed to the administration, while its enemies insisted that it had produced the crisis by unnecessarily contracting credits for political effect. It is impossible now to decide the controversy impartially. The difficulties of the Bank increased until it collapsed. Its president and four others were criminally prosecuted. Biddle died insolvent and broken-hearted. The removal of the deposits was denounced at the time by Webster, Clay, Calhoun and all the Congressional leaders. The Senate rejected Taney's nomination as Secretary of the Treasury after he had held the office nine months. This was the first time that the Senate had ever rejected a Cabinet appointment.

Taney returned to his legal practice and received ovations from Jackson's partisans. The President did not forget his obedient servant. In January, 1835, President Jackson nominated Taney for a seat on the Supreme Bench, and the Senate postponed consideration indefinitely. But the President was not to be balked. After Chief Justice Marshall died, he nominated Taney as his successor. In spite of the opposition of Clay and Webster, Taney's nomination was confirmed on March 15, 1836. From this time his history is merged in that of the Supreme Court. His opinions, so far as political questions were involved, tended to support State rights and decentralization, thus taking an opposite direction from those of Marshall. From 1836 to 1861 his opinions as circuit judge were reported by his son-in-law, J. M. Campbell. His other decisions are in "Supreme Court Reports."

The most famous of his decisions was that in the Dred Scott case in 1857, from which only Justices J. McLean and B. R. Curtis dissented. The negro Dred Scott had been a slave, and had been taken by his master, Dr. Emerson, an army surgeon, to Rock Island in 1834, thence to Fort Snelling, and back to Missouri in 1838. He sued for his freedom on the ground of having been taken into Illinois, a free State. The case was carried to the Supreme Court on questions of conflict between the laws of Missouri and Illinois. The primary questions were as follows:—Could a negro, whose ancestors were imported from Africa as slaves, become an American citizen? and, Did the slave's residence in a free State render him free? Chief Justice Taney in his decision explained that it was not the province of the Court to decide on the justice or policy of the law, but simply to interpret and administer it. Nevertheless the opinion did travel beyond the legal issues involved and introduced this memorable declaration about the status of negroes at the formation of the Union: "They had for more than a century been regarded as beings of an inferior order and altogether unfit to associate with the white race either in social or political relations; and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect, and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit." Although these words were rhetorical and not a legal conclusion, the decision was in keeping with them and denied Scott's citizenship and right to sue in the United States Courts. It also declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, and virtually made slavery national. Taney's object was, undoubtedly, to put a stop to the anti-slavery agitation, by proving that slavery was imbedded in the Constitution, for which all citizens, except a few ultra Abolitionists, professed the greatest reverence. But the course of events carried the Northern people beyond that point. Their respect for the Constitution and for the Supreme Court was sadly shaken. They went back to the spirit of liberty in the Declaration of Independence. The Southern people, on the other hand, were delighted and became reckless. The difference between the two sections was brought to issue in the Presidential election of 1860 and decided by the Civil War.

When martial law was proclaimed in Maryland in 1861, Chief Justice Taney ordered the release of a prisoner seized by General Cadwalader, and denied the right of the President to suspend the writ of habeas corpus. In 1863, in a letter to the Secretary of the Treasury, he maintained that the act of Congress taxing the salaries of United States judges was unconstitutional. He died at Baltimore, October 12, 1864, and was buried at Frederick, Maryland.

Taney was an upright, kindly man, exemplary in his private life, inclined to fastidiousness in habit excepting that he was an inveterate smoker. He freed his slaves as soon as he inherited them, and pensioned the aged ones. In manner he was graceful and affable, yet dignified. His health was delicate and his temper quick, but by watchfulness he had acquired perfect self-control. He was very industrious, a close student and courageous in the expression of his opinion. He had wider experience as a lawyer than any of his predecessors, but he was hardly ever out of his native region, and he held the limited views of his section, yet at times his views have great judicial breadth. The error which has tarnished his fame was due to an earnest desire to allay sectional strife, but the reaction against the means employed produced tenfold more trouble and disaster.

THE DRED SCOTT DECISION. (March 7, 1857.)

From the consideration of questions such as ordinarily arise the Court glided at a single turn to the brink of a fearful precipice. No monitory shuddering warned them of impending ruin. The broad current of decision and of argument flowed on as usual, unbroken by hidden obstructions or whirling eddies, as smooth as the glassy surface of a descending stream upon the very edge of its fall. In a moment they became involved. The wild passions of the Kansas-Nebraska struggle had reached the Court. The agony of the conflict between slavery and freedom, which touched the tongue of Phillips with fire and raised the soul of Sumner to the stars, had wrapped them in its frenzy, and in a moment of bewilderment they believed that they had the judicial power to deal with a political and moral question, and by a judgment, which they vainly endeavored to induce the country to believe was not extra-judicial, to settle the most agitated question of the day. The judgment was pronounced, but was promptly reversed by the dread tribunal of War.

At the December term, in the year 1856, the case of Dred Scott, plaintiff in error, v. John F. A. Sandford, stood for a second argument, on two questions stated by an order of the Court to be argued at the bar. The first question was whether Congress had constitutional authority to exclude slavery from the Territories of the United States, or in other words, whether the Missouri Compromise Act, which excluded slavery from the whole of the Louisiana Territory, north of the parallel 36° 30', was a constitutionally valid law. The second question was whether a free negro of African descent, whose ancestors were imported into this country and sold as slaves, could be a citizen of the United States, under the Judiciary Act, and as a citizen could sue in the Circuit Court of the United States.

The action had been brought by Scott in the Circuit Court of the United States for the district of Missouri, to establish the freedom of himself, his wife and their two children. In order to give the court jurisdiction of the case, he described himself as a citizen of the State of Missouri, and the defendant, who was the administrator of his reputed master, as a citizen of the State of New York. A plea to the jurisdiction was filed, alleging that the plaintiff was not a citizen of Missouri, because he was a negro of African descent, whose ancestors were of pure African blood, and were brought into this country and sold as slaves. To this plea there was a general demurrer, which was sustained by the court and defendant was ordered to answer over. A plea to the merits was then entered, to the effect that the plaintiff and his wife and children were negro slaves, the property of the defendant. The case went to trial, and the jury, under an instruction from the Court upon the facts of the case that the law was with the defendant, found a verdict against the plaintiff, upon which judgment was entered, and the case was then brought upon exceptions by writ of error to the Supreme Court of the United States.

It is clear that the first question raised by the record arose under the plea to the jurisdiction of Circuit Court, and after a careful study of the opinions and dissenting opinions, it is equally clear that if it had been decided by the Supreme Court that Scott was not a citizen by reason of his African descent, the only thing that could be properly done would be to direct the Circuit Court to dismiss the case for want of jurisdiction, without looking to the question raised by the plea to the merits. But if the Court should decide that he was a citizen notwithstanding his African descent, then the question raised by the plea to the merits relating to his personal status as affected by his residence in a free territory and his return to Missouri would have to be acted upon. This latter question involved the Constitutional power of Congress to prohibit slavery in that part of Louisiana territory purchased by the United States from France, and also the collateral question as to the effect to be given to a resident in the free State of Illinois, and a subsequent return to Missouri. Upon an action brought in the State Court many years prior, the Supreme Court of Missouri had held Scott to be still a slave, upon the broad ground that no law of any other State or Territory could operate in Missouri upon personal status, even if he did become an inhabitant of such other State or Territory.

The case was first argued before the Supreme Court ot the United States at the December term of 1855, and it was found, after consideration and comparison of views, that it was not necessary to decide the question of Scott's citizenship under the plea to the jurisdiction, but that the case should be disposed of by an examination of the merits. Mr. Justice Nelson was assigned to write the opinion of the court upon this view of the case, from which, however, Justices McLean and Curtis dissented. The opinion prepared by Nelson, judging from its internal evidence, as well as the history of it given by him, was designed to be delivered as the opinion of the majority of the bench, and in disposing of the plea to the jurisdiction, he said: " In the view which we have taken of the case, it will not be necessary to pass upon this question, and we shall therefore proceed at once to an examination of the case upon its merits. The question upon the merits, in general terms, is whether or not the removal of the plaintiff, who was a slave, with his master from the State of Missouri to the State of Illinois with the view to a temporary residence, and after such residence and return to the slave State, such residence in the free State works emancipation." The opinion then disposed of the case upon the ground that the highest court in the State of Missouri had decided that the original condition of Scott had not changed and that this was a question of the law of Missouri on which the Supreme Court of the United States should follow the law as it had been laid down by the highest tribunal of the State. The conclusion reached by the opinion was not that the case should be dismissed for want of jurisdiction, but that the judgment of the Circuit Court which had held Scott to be still a slave should be affirmed. Shortly after this, however, a motion was made by Mr. Justice Wayne, in a conference of the court for a reargument of the case, and the two questions, which we have stated at the outset of our discussion of the matter, were carefully framed by the Chief Justice to be argued at the bar de novo. The cause was argued by Montgomery Blair and George Ticknor Curtis, in behalf of the plaintiff in error, and Reverdy Johnson and Senator Geyer, of Missouri, for the slave owner.

At the second argument Mr. Justice Wayne became fully convinced that it was practicable for the Supreme Court of the United States to quiet all agitation on the question of slavery in the Territories by affirming that Congress had no Constitutional power o prohibit its introduction, and, unfortunately for himself, his associates, and the country, persuaded the Chief Justice and Justices Grier and Catron of the public expediency of this course. The opinion of the Court was then pronounced by Chief Justice Taney, in which Mr. Justice Wayne absolutely concurred. Mr. Justice Nelson read his own opinion, which had been previously prepared as that of the Court. Mr. Justice Grier concurred in Nelson's opinion and was of opinion also that the Act of 6th March, 1820, known as the " Missouri Compromise" was unconstitutional and void, as stated by the Chief Justice. Justices Daniel and Campbell concurred generally with the Chief Justice, while Mr. Justice Catron thought that the judgment upon the plea in abatement was not open to examination in this Court, and concurred generally with the Chief Justice upon the other points involved. Justices McLean and Curtis alone dissented, the former stating that the judgment given by the Circuit Court on the plea in abatement was final. He was also of opinion that a free negro was a citizen, and that the Constitution justified the Act of Congress in prohibiting slavery, and further that the judgment of the Supreme Court of Missouri pronouncing Scott to be a slave was illegal, and of no authority in the Federal Court. . . .

No portion of Chief Justice Taney's opinion is more labored or constrained than the effort to show that, after disposing of the plea in abatement, which, when sustained as it had been upon demurrer, ousted the jurisdiction of the Court, the Court had still a right to enter upon a discussion of the merits of the case. And no part of the dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice Curtis is more powerful, from a legal point of view, than his consideration of the doctrines of pleading involved, and fairly arising out of the state of the record.

The Chief Justice used the following language, after having shown historically that at the time of the adoption of the Constitution of the United States free negroes were not citizens: "They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race either in social or political relations ; and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold, and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic whenever a profit could be made by it. This opinion was at that time fixed and universal in the civilized portion of the white race."

The injustice which has been done to Chief Justice Taney consists in the partisan use which was made of the single phrase, "That they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." The words were violently torn from the context of the opinion, and quoted as though the Chief Justice had intended to express his own individual views upon the question, naturally raising a storm of indignation at their inhumanity and barbarity. That such were not the personal views of the Chief Justice, no careful or conscientious student of his life can for a moment suppose; he had long before manumitted all his own slaves, had never refused his professional aid to negroes seeking the rights of freedom ; had even defended a person indicted for inciting slaves to insurrection, at a time when the community were violently excited against the offender and against Taney himself for his defense, and, when pressed with the gravest business, has been known to stop in the streets of Washington to help a negro child home with a pail of water. He was, moreover, a man of the greatest kindness, charity, and sympathy. The real wrong-doing of which the Chief Justice was guilty was in attempting by extra-judicial utterances to enter upon thesettlement of questions purely political, which were beyond the pale of judicial authority, and which no prudent judge would have undertaken to discuss. It was a blunder worse than a crime, from the consequences of which he and his associates can never escape.—HAMPTON I. CARSON.