Bleeding Kansas (Roark, 2002)

Textbook

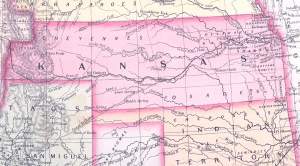

Fighting broke out on the morning of May 21, 1856, when a mob of several hundred proslavery men entered the town of Lawrence, the center of free-state settlement. Only one man died - a proslavery raider who was killed when a burning wall collapsed - but the 'Sack of Lawrence,' as free-soil forces called it, inflamed northern opinion. In Kansas, news of Lawrence provoked one free-soil settler, John Brown, to 'fight fire with fire.' Announcing that 'it was better that a score of bad men should die than that one man who came here to make Kansas a Free State should be driven out,' he led the posse that massacred five allegedly proslavery settlers along the Pottawatomie Creek. After that, guerilla war engulfed the territory.

James L. Roark, et al., eds., The American Promise: A History of the United States, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2002), 473.