John Brown (American National Biography)

Scholarship

Though a military fiasco, Brown's raid was for many a jeremiad against a nation that defied God in tolerating human bondage. It sent tremors of horror throughout the South and gave secessionists a persuasive symbol of northern hostility. It hardened positions over slavery everywhere. It helped to discredit Stephen A. Douglas's compromise policy of popular sovereignty and to divide the Democratic party, thus ensuring the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860. In a longer view, African Americans especially have seen in Brown hope for the eventual redemption of an oppressive America, while critics have condemned his extremism and deplored his divisive impact on the sectional crisis. Both Brown's fanaticism and his passion for freedom make him an enduring icon.

Robert McGlone, "Brown, John," American National Biography Online, February 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00096.html.

John Brown (Boyer, 1973)

Scholarship

More than a rural eccentric, although he was also that, this was the man in whom public concern mounted during the three years beginning in 1856 until his name was a curse or a prayer in the mouth of every American who could read or hear his fellows talk or had any degree of mental sentience. By 1859, John Brown was not only universally known but a national agony dividing the country and it is within this division that his memory, his reputation, and his historic role have always been judged.

Virtually all of the testimony concerning him - save that which precedes his fame and the controversy it aroused - lies within this great national division. In general that testimony, despite many variations, was passionately for John Brown when offered by those who believed that slavery was killing the nation and that any sacrifice or any violence was justified in destroying it. It was equally passionate but vehemently against him when uttered by those favoring slavery, or who felt that civil war was too high a price to pay for its destruction, or that black freedom was not quite worth white men's blood, or that violence against slaves did not excuse John Brown's violence against slaveholders. Judgment usually had more to do with political conviction and political necessity, with sectional sympathy and party affiliation, than it did with the character of John Brown.

Virtually all of the testimony concerning him - save that which precedes his fame and the controversy it aroused - lies within this great national division. In general that testimony, despite many variations, was passionately for John Brown when offered by those who believed that slavery was killing the nation and that any sacrifice or any violence was justified in destroying it. It was equally passionate but vehemently against him when uttered by those favoring slavery, or who felt that civil war was too high a price to pay for its destruction, or that black freedom was not quite worth white men's blood, or that violence against slaves did not excuse John Brown's violence against slaveholders. Judgment usually had more to do with political conviction and political necessity, with sectional sympathy and party affiliation, than it did with the character of John Brown.

Richard O. Boyer, The Legend of John Brown: A Biography and History (New York: Alfred A. Knoph, 1973), 127.

John Brown (Reynolds, 2005)

Scholarship

John Brown planted the seeds for the civil rights movement by making a pioneering demand for compete social and political equality for America's ethnic minorities. To be sure, many other Americans have contributed to civil rights. But only one white reformer lived continuously among blacks, penned a revised American constitution awarding them full rights, and gave his life in a violent effort to liberate the slaves. That's why the Second Niagara Movement (which became the NAACP), the forerunner of the civil rights movement, hailed Brown as one "who had no predecessors, and can have no successors." And that's why no other white person in American history has been more beloved over time among African Americans than John Brown.

It may be discomfiting to think that some of America's greatest social liberties sprang in part from a man who can be viewed as a terrorist. But John Brown was a man not only of violence but of eloquence and firmness of principle. His widely reprinted declarations against slavery impressed the intellectual leaders Ralph Waldo Emerson, who said Brown's speech to Virginia court was as great as the Gettysburg Address, and Henry David Thoreau, who declared that Brown's words were more powerful than his rifles.

It may be discomfiting to think that some of America's greatest social liberties sprang in part from a man who can be viewed as a terrorist. But John Brown was a man not only of violence but of eloquence and firmness of principle. His widely reprinted declarations against slavery impressed the intellectual leaders Ralph Waldo Emerson, who said Brown's speech to Virginia court was as great as the Gettysburg Address, and Henry David Thoreau, who declared that Brown's words were more powerful than his rifles.

David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, rev. ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), x.

John Brown, Birth (Reynolds, 2005)

Scholarship

Into this unusual family atmosphere of fervent Calvinism and equally fervent Abolitionism, John Brown was born on May 9, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut. Had he appeared at a different historical moment, it is quite possible that Harpers Ferry would not have happened - if so, the Civil War might have been delayed, and slavery might not have been abolished in America as soon as it was.

David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, rev. ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 23.

John Brown, Marriage to Dianthe Lusk (Renehan, 1997)

Scholarship

[John Brown's] first wife was nineteen-year-old Dianthe Lusk, whom he married when he was twenty. Like him, she was solemn and puritanical. She was also a manic-depressive: sensitive, scared, easily tearful. Dianthe suffered at least one nervous breakdown and was afflicted with what a friend called "an almost constant blueness and melancholy." Some neighbors called her a madwomen. She was capable of silences that lasted for days, these interrupted by only the submissive "Yes, husband" that the domineering John Brown expected and got whenever he asked anything of her. Eight children arrived in rapid succession during the eleven years between 1821 and 1832. The six who survived would remember their mother as sad, their father as severe.

Edward J. Renehan, Jr., The Secret Six: The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired with John Brown (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997), 22.

John Brown, Marriage to Mary Ann Day (Reynolds, 2005)

Scholarship

[John] Brown…took on a housekeeper whose sixteen-year-old sister, Mary Day, came occasionally to spin cloth. Mary caught his eye as she sat at her spinning wheel. Tall and deep bosomed, she had striking black hair and a sturdy frame. The daughter of Charles Day, a blacksmith and farmer in nearby Troy Township, she had little formal education but impressed Brown as a practical, hardworking woman. It wasn't long before Brown, too bashful to propose verbally, presented her with a written offer of marriage. The girl nervously put his note under her pillow and slept on it a night before opening it. After reading it, she grabbed a bucket and rushed off to a spring to fetch water. Brown followed her. By the time the two returned to the house, he had received the answer he wanted. They were married on June 14, 1833. Ten months later a baby girl, Sarah, arrived.

David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, rev. ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 49.

John Brown, Response to Elijah Lovejoy Murder (Reynolds, 2005)

Scholarship

As the meeting drew to a close, John Brown suddenly rose, lifted his right hand, and said, "Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!" His aged father then stood up and with his characteristic stammer added, "When John the Baptist was beheaded, the disciples took up his body and laid it in a tomb and went and told Jesus. Let us go to Jesus and tell him." Tears flowed down his wrinkled face as he led the meeting in prayer. No longer was John Brown working in secret. A murder committed by a proslavery mob had drawn from him a vow to fight slavery. The circumstances of his oath were telling. He was responding to a man who was an inchoate version of what he would later become. Elijah Lovejoy had risked his life by defending blacks publicly, as would Brown. Also like Brown, he persevered in his battle despite setback, and when faced with defeat he consciously chose the role of the Christ-like martyr.

David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, rev. ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 65.

John Brown, Response to Elijah Lovejoy Murder (Stauffer, 2002)

Scholarship

John Brown was among the many reformers who considered Elijah Lovejoy's murder the spark that fired his fervent abolitionism. But Brown's reference to Lovejoy's martyrdom needs to be understood within the context of social and religious forces that transformed him into a militant abolitionist…Lovejoy's death certainly upset Brown, but it was not so much the event itself that led to Brown's oath. Rather, Lovejoy's death signified for Brown all that was wrong in the country, much the same way that the Slave Power later symbolized for Northerners the source of their fears and anxieties. Lovejoy's death coincided with a series of tragedies in Brown's life, culminating in the panic of 1837, that made him want to replace his existing world with his millennialist and perfectionist vision.

John Stauffer, The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 118-119.

John Brown, Radical Abolition Party Convention in 1855 (Stauffer, 2002)

Scholarship

The inaugural convention of Radical Abolitionists has been largely forgotten in American history, and the party it launched won few votes and never elected a candidate to office. In fact the party itself lasted only five years and never polled more than a few thousand votes in a single election. But the convention that gave birth to the Radical Abolition party has deep cultural relevance: it marked an unprecedented moment of interracial unity and collapsing of racial barriers. It is the only recorded moment at which Gerrit Smith, James McCune Smith, Frederick Douglass, and John Brown were all in the same place. Despite their close friendship, which began in the late 1840s, they lived in different parts of New York State and had few opportunities to be together. The convention gave tangible shape to their goals for ending slavery, their hopes for their country, and the means for realizing their dreams of a new world. They arrived with high expectations, and left feeling elated by what had transpired. But the convention also marked the crossing of a Rubicon, for the party’s platform specifically affirmed violence as a way to end slavery and oppression. The embrace of violence would eventually destroy the four men’s alliance.

John Stauffer, The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 8-9.

John Brown, Pottawatomie Creek Attack (Freehling, 2007)

Scholarship

"John Brown, the same warrior who would assault Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859, massed six followers, including four of his sons, against slumbering proslavery settlers on the Pottawatomie Creek, some thirty miles south of Lawrence. Brown and his henchman dragged some five men from rude log cabins. They shot their victims, slit them open, and mutilated their corpses. With Brown’s celebration of an eye for an eye, the nation’s problem was not just that proslavery violence spawned antislavery violence. The worse problem was that more Kansas and more Northerners than John Brown, whatever they thought of black slavery, already preferred civil war to slaveholder repressions of white men’s republicanism. Thanks to the aftermath of the Kansas-Nebraska Act that Davy Atchison’s followers had spawned, a continuing Kansas crisis loomed huge on the national horizon."

William W. Freehling, Secessionists Triumphant, 1854-1861, vol. 2 of The Road to Disunion (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 79.

John Brown, Pottawatomie Creek Attack (Stauffer, 2002)

Scholarship

On the night of May 24, Brown and a group of seven men cut the throats of five unarmed proslavery settlers and hacked them to death with broadswords. Brown's actions need to be understood within the context of the Radical Abolition party and its doctrines. Brown is often described as unique among abolitionists, the ne plus ultra of fanatics, but he is seldom associated with political abolitionism. Yet he aligned himself closely with Gerrit Smith, McCune Smith, and Douglass, attended other political conventions with them, and justified his actions under God and the Radical Abolitionist message that whatever was right was practicable, to paraphrase Douglass. Brown and his comrades were not far removed from Preston Brooks and the thousands of Southerners who sent him canes of congratulation: both sides advocated violent means for realizing wholly different visions of their country. But the two men's uses of violence differed in two ways. First, Brooks used violence to defend his (and the South's) honor, while Brown used violence to defend his (and Radical Abolitionists') vision of social equality. Second, Sumner had challenged and provoked Brooks with his speech; Brown's victims had done nothing directly to provoke or challenge Brown and his men.

John Stauffer, The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 21-22.

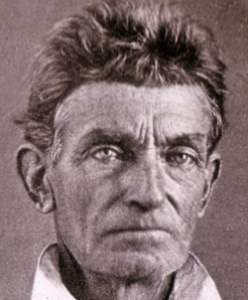

John Brown, September 1856 Daguerreotype (Stauffer, 2002)

Scholarship

In September 1856 John Brown sat for his portrait…Although he was not yet well known at the national level, he was quickly gaining fame as a freedom fighter in Kansas. As his reputation for militant abolitionism grew, he increasingly sat for his "likeness." He had numerous portraits taken of him while in Kansas, and preferred to have black artists or abolitionists represent him. This daguerreotype was created by John Bowles, a Kentucky slaveowner who had emancipated his slaves and became an abolitionist and comrade of Brown in Kansas. Bowles was quite familiar with Brown's willingness to befriend and identify himself with blacks, and one might argue that he portrays Brown as someone who blurs the line between black and white: the daguerreotype is slightly underexposed, rendering Brown's tanned skin even darker than it actually was. Brown's face appears tawny, as dark as Douglass' in the frontispiece of My Bondage.

John Stauffer, The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 56-58.

John Brown, 1857 Speech in Concord (Reynolds, 2005)

Scholarship

"As during his visit in 1857, Brown gave a public lecture in the Concord Town Hall. Emerson, Thoreau, and Alcott were among those in attendance. Brown talked about Kansas and dropped hints about Virginia. Without revealing plans, he said he was prepared to strike a dramatic blow for freedom by running off slaves in an effort to render insecure the institution of slavery. The Transcendentalists' enthusiasm for Brown was stronger than ever. They thought he looked like an apostle, with his flowing white beard, his intense grayish eyes, and his aquiline nose, slightly hooked above his firm lips…For Alcott, as for Emerson and Thoreau, Brown embodied the higher law, principled violence, and self-reliance."

David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, rev. ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 290.

John Brown, Missouri Raid Overview (Renehan, 1997)

Scholarship

Five days before Christmas, 1858, John Brown led his men on a raid into Missouri during which the homes of two slave owners were plundered. One of the slaveowners was executed - shot in the head. Eleven slaves were liberated. Brown also liberated several wagons, many horses and mules, five guns, and nearly $100 in cash. The Missouri General Assembly condemned the incursion and suggested the possibility of violent retaliation. Moderate free-state Kansas such as Charles Robinson and George Washington Brown of the Lawrence Herald of Freedom criticized Brown's action, saying that it invited the resurgence of border war by giving Missourians an excuse to invade and terrorize free-state communities under cloak of searching for stolen property. The governor of Missouri offered $75 for Brown's capture. And President Buchanan was so enraged that he personally put a $250 price on Brown's head. (Brown, in turn, mockingly offered a reward of $2.50 for Buchanan's capture.) Back East, the unpredictable Gerrit Smith surprised his wife by being delighted with the news of Brown's activity.

Edward J. Renehan, Jr., The Secret Six: The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired with John Brown (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997), 179.

John Brown, Missouri Raid Overview (Reynolds, 2005)

Scholarship

The opportunity came in mid-December when [John Brown's] Free State friend George B. Gill told him he had just been visited by a black man, Jim Daniels, who was held in slavery by a Missourian named Harvey G. Hicklan (or Hicklin). Daniels, disguised as a broom salesman, had snuck across the state line and reported to Gill that he, his pregnant wife, and their two children were on the verge of being sold to a Texas slave-owner. Brown assured Gill he would help Daniels…On the night of December 20-21, he rode with twenty men into Vernon County, Missouri. As he approached the Little Ossage River, he divided his party. Twelve went with him to the area north of the river and the rest with Aaron Stevens to the south side. The goal was to liberate slaves, and if necessary, take whites as hostages.

David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, rev. ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 278.

John Brown, Returns to Kansas after Missouri Raid (Reynolds, 2005)

Scholarship

[John] Brown and [Aaron] Stevens joined up at daybreak. Between them, they had eleven blacks representing four families: Jim Daniels with his wife and children; a widowed mother with two daughters and a son; a young man and a boy who were brothers; and a woman who had been forced to live separately from her husband…The blacks were taken thirty-five miles to Augustus Wattle's cabin in Moneka, Kansas, near Osawatomie. Before joining them Brown lingered near the state line to watch for any Missourians who might try to retaliate for his act. Subsequently, the blacks were moved to the home of Dr. James G. Blount, near Garnett. There, Brown built strong earthworks in case of attempted reprisal.

David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, rev. ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 279.

John Brown, Tabor residents criticize Missouri raid (Carton, 2006)

Scholarship

Full of his success and renewed notoriety, Brown expected a hero's welcome in the town of Tabor, where he had recuperated after his Kansas campaigns in the summer of 1856. But the town's residents, though solidly antislavery, were repelled by the violent circumstances of this particular slave rescue and by the lawless appropriation of property that had accompanied the relief of oppressed people. When Brown strode into the church of his friend Reverend John Todd on the Sunday after his arrival and requested that the minister offer a public thanksgiving for God's preservation of the fugitives and their liberators, the gesture seemed to many of Todd's parishioners more imperious than pious. Brown's petition was deferred until a meeting could be held to discuss it. The result was not a public thanksgiving but a public rebuke: "While we sympathize with the oppressed, and will do all that we conscientiously can to help them in their efforts for freedom, the people of Tabor formally resolved, "we have no sympathy with those who go to slave states, to entice away slaves, and take property or life when necessary to attain that end."

Evan Carton, Patriotic Treason: John Brown and the Soul of America (New York: Free Press, 2006), 274-275.

John Brown, Harpers Ferry Attack (Freehling, 2007)

Scholarship

On the evening of October 16, 1859, the liberator led fourteen other whites and four blacks from his rented Kennedy Farm in Maryland to Harpers Ferry, those six miles distant. There the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers unite to heave against a jagged semimountain, before flowing on to the sea….There transpired one of the most stupendous scenes in American history. In the dark night, Brown's freedom fighters easily captured Harpers Ferry's federal armory, arsenal, and engine house…No other first strike has ever been better planned or carried out (which is only to say that John Brown here perfected his lifelong specialty). No other following tactics have ever been botched so badly (which is only to say that John Brown here succumbed to his lifelong flaw). Where these raiders meant to kill whites, in order to free blacks, they first killed a free black, Shepard Hayward, as he walked harmlessly away from them.

William W. Freehling, Secessionists Triumphant, 1854-1861, vol. 2 of The Road to Disunion (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 211-212.

John Brown, Harpers Ferry Attack (Oakes, 2007)

Scholarship

At dusk on the evening of October 16, 1859, acting on direct orders from the Lord God Himself, John Brown led a band of eighteen men on a raid of the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry in western Virginia. By midnight Brown's men had cut the telegraph wires and commandeered the railroad bridges leading into town. They had control of the arsenal, the armory, and the rifle factory. Then they sat back and waited for slaves from the surrounding countryside to join their rebellion. But the slaves never came. About twenty were brought into town by Brown's men, but they refused to join the fight, and most of them had the good sense to run for their lives. Little more than a year later slaves across the South began claiming their freedom by running in substantial numbers to armed white northerners invading the South, this time as Union soldiers. But the slaves at Harpers Ferry stayed put; they knew the differences between an army of liberation and a ship of fools. By morning Brown's men had been surrounded. Within thirty-six hours it was all over. A handful of Brown's men escaped. Several were killed, including two of Brown's sons. Brown and two others were captured, tried, and executed.

James Oakes, The Radical and The Republican: Fredrick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York: W W Norton & Company, 2007), 94-95.

John Brown, Harpers Ferry Attack (Reynolds, 2005)

Scholarship

The raid on Harpers Ferry helped dislodge slavery, but not in the way Brown had foreseen. It did not ignite slave uprisings throughout the South. Instead, it had an immense impact because of the way Brown behaved during and after it, and the way it was perceived by key figures on both sides of the slavery divide. The raid did not cause the storm. John Brown and the reaction to him did.

David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, rev. ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 309.

John Brown, Harpers Ferry Attack (Stauffer, 2002)

Scholarship

Although the outcome of the raid would undoubtedly have been the same, more blacks might have come to his aid had Brown’s timing been better. Almost every analysis of the raid asserts that slaves and free flacks ignored Brown’s efforts on their behalf, but some evidence – much of it stemming from oral tradition – suggests that free blacks in Jefferson County and throughout the North and Canada knew of Brown’s plans and were prepared to join him. Brown originally scheduled the raid for July 4, 1858 (reflecting his fondness for symbolic value), but the date was postponed when one of his comrades, Hugh Forbes, turned traitor and threatened to expose the raid unless he received money…Evidently, his attack caught a number of his allies by surprise: Richard Hinton was in nearby Chambersburg “at a black-operated underground railroad post,” awaiting word to join Brown. Harriet Tubman, was trying to recruit followers. And a group of blacks from Ontario, Canada, were near Detroit, and supposedly on their way to join Brown.

John Stauffer, The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 255-256.