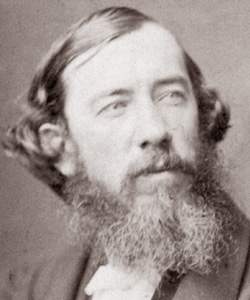

Moncure Conway (American National Biography)

Moncure Conway (Notable Americans)

Moncure Conway, Background and Personality (d'Entremont, 1987)

Moncure Conway, Changing Philosophies (d'Entremont, 1987)

Moncure Conway, Liberating his Father's Slaves (d'Entremont, 1987)

Moncure Conway (Dickinson Chronicles)

Graduating from Harvard in 1854, he first took the Unitarian pulpit in Washington, D.C. His time in the capital was not a happy one, however. In theology Conway was becoming more radical, while his views on emancipation recommended the minority opinion that disunion was preferable to civil war. An independent South would be left to work out emancipation through the moral example of the North. This opinion pleased few members of his congregation on either side of the question, and he was relieved to take up a position in Cincinnati in late 1855 having despaired of advancing abolitionism with work in the south itself. In Ohio, a far more liberal membership welcomed him and he was able to continue his development in both study and writing. He also married Ellen Dana, the daughter of Charles Dana, and together the couple formed a strengthening partnership that ended with them leaving the Unitarian Church.

Meanwhile, Conway's greatest fears were realized with the outbreak of the Civil War and the splitting of both his family and his abiding love for his home state of Virginia. Still, he accepted a mission on behalf of northern abolitionists to explain anti-slavery and the Union cause to a divided Britain. He traveled to London in April 1863 and was well received in intellectual circles, befriending another one of his early heroes, Thomas Carlyle, as well as Robert Browning. But with a personal enthusiasm that overwhelmed his limited skills as a diplomat, he precipitously offered the Confederate representative in Britain, James Murray Mason, the full opposition of northern abolitionists to any further prosecution of the war in exchange for immediate emancipation of all slaves held in the Confederate states. Mason rebuffed him publicly, American abolitionism immediately disowned him, and he prudently explained himself to the United States ambassador, Charles Francis Adams, apologizing for any appearance of treason in his remarks. Feeling cut off from home, North and South, he took up an appointment at the South Place Chapel in London. The South Place Society, later the South Place Ethical Society, had been founded fifty years before on the ideals of personal virtue superceding faith or doctrine and Conway's new post gave him the opportunity to bloom as a student of religion and free thought. The more open intellectual climate of Britain also helped his exchanges of ideas with people as diverse as Swinburne, the Rossettis, and Annie Besant. Conway stayed for seventeen years, lecturing, traveling, and publishing some of his most well-known and memorable works.

When he returned to the United States in 1884 upon the death of his father, his publications had rehabilitated his reputation. This standing he enhanced with further works on Edmund Randolph, George Washington, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Thomas Paine to the point that his increasingly conservative alma mater awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1892 and asked him to serve as a trustee. In 1892, however, he returned to London and his position at the South Place Society. This tenure was cut short five years later in tragic circumstances when he was forced to bring his ailing wife home to die in New York on Christmas Day, 1897. The devoted couple had raised three children: two sons, Eustace (1859) and Dana (1865), and a daughter, Mildred (1868), who would later marry the accomplished architect Phillip Sawyer.

With the loss of his life's companion, coupled with the imperialistic "spreadeaglism" that he saw as afflicting his country in the advent of the Spanish-American War, Conway left his homeland again. He lived the remainder of his life mostly in Paris and London, with periodic visits to lecture in the United States, writing further on Paine (including a two-volume biography), and speaking in the cause of free thought and world peace. In 1905, his friend Andrew Carnegie donated funds to Dickinson College for the construction of Conway Hall which was used as the preparatory school until 1917 and then served as a freshman residence hall. Moncure Daniel Conway died alone amidst his books and writings in his Paris apartment on November 15, 1907. He was seventy-five years old.

Moncure Conway (New York Times)

PARIS, Nov. 18.—the body of the Rev. Moncure D. Conway of New York, the distinguished American author who died here suddenly Nov. 15, was cremated at the Père Lachaise Cemetery to-day, in the presence of many friends. The ashes will probably be sent to the United States later.

Moncure Conway (New York Observer and Chronicle)

Moncure D. Conway

The Rev. Moncure D. Conway, D.D., died in Paris on November 15. He was born in Stafford County, Va., March 17, 1832. he was educated at the schools in Fredericksburg, Va., and at Dickinson College, Pennsylvania, from which institution he was graduated in 1849. After studying law, he became a writer for the Richmond Examiner. Mr. Conway then entered the Methodist ministry. Soon thereafter he entered the Divinity School at Cambridge, Mass. He was graduated in 1854, and returned to the South. From Falmouth he went to Washington, where he became the pastor of the Unitarian Church, from which pastorate he was dismissed on account of his radical anti-slavery discourses. He next went to Cincinnati as pastor of the Unitarian Church there. After a short time in Boston, in 1863, Mr. Conway went to England, and in less than a year he had become the pastor of South Place Chapel, London, where he remained until 1884, when he returned to the United States. Mr. Conway became a warm admirer and friend of Abraham Lincoln, and left many interesting reminiscences of that friendship. He was a member of several learned societies in London, lectured occasionally at the Royal Institute, and in New York was a member of many clubs.